Austin, Indiana, hard-hit by the opioid crisis, made national headlines in 2015 after an HIV outbreak swept through this rural town of about 4,200 people. Now, as Austin recovers, its local high school is leveraging major philanthropic dollars to revamp its counseling efforts.

But since these funds can’t be used to hire more school counselors, leaders at Austin High School are asking classroom teachers to provide students additional social-emotional support. To that end, the school is transforming its daily homeroom period into a time to discuss healthy life choices, professional development, and financial planning, among other issues.

The town’s HIV outbreak put a spotlight on the local high school and the role it could play in helping students overcome the crisis, according to Cindy Watts and Nicole Kilburn, a school counselor and social worker, respectively. Between 2011 and 2015, some 215 people in Scott County were infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and the epidemic had local educators discussing how best to support Austin students through — and beyond — the crisis.

“We have very few discipline issues because this is a hardworking community where kids respect adults,” Watts said. “But kids in our community have had to be resilient. The kids were really innocent [during the crisis] … but they were affected.”

At the same time, the outbreak was sweeping the Austin community, the Indianapolis-based Lilly Endowment was preparing to announce its Comprehensive Counseling Initiative. The goal: To create meaningful counseling programs to help Indiana students develop healthy habits, and to better prepare them for college and careers.

When Watts learned about this grant opportunity, she and her colleagues at the larger Scottsburg High School nearby submitted a joint application — and were awarded more than $381,800 between them. (The Lilly Endowment also supports Chalkbeat. Learn more about our funding here.)

For Austin High School, that meant an infusion of close to $100,000, which allowed school officials to work with organizations like the Indiana Youth Institute and the American Student Achievement Institute, and to outline plans for better supporting social-emotional needs. The money was part of one-time grants designed to improve existing resources and staff, and couldn’t be used to make new hires.

Even though the school is technically within the student-to-counselor ratio recommended by the American School Counselors Association (that is, one counselor for every 250 students), Watts said another full-time counselor would help with student achievement and crisis management. Instead, the district looked to their teachers to provide more emotional support to their many students in need.

What they decided to do was capitalize on the 30-minute homeroom periods, also called “Pride Time,” which start at 10:50 a.m. each day. In the past, this time was used largely for test preparation and studying, though teachers found moments to have deeper conversations about academic success and personal well-being.

Now, teachers will work with the same homeroom cohort year after year and cycle through a guided curriculum designed by a committee of Austin High School teachers. Each month, homeroom classes will focus on a different theme. One month this fall, for example, freshman will discuss relationship-building, while seniors will focus on job interviews.

Although there hasn’t been a lot of formal training, teachers will adhere to the homeroom curriculum they developed, and they are encouraged to reach out to the school’s counseling department for guidance along the way.

Ryan Stuckwish, a government and economics teacher who headed a committee that developed the homeroom curriculum, said he knows that many teachers were already having these conversations. But he believes that a formal model for engaging in this way could help strengthen trust between faculty and students, and also can help staff better identify students with pressing needs. Still, high teacher turnover means many Austin students won’t have the same homeroom teachers for all four years of high school.

“These are challenging students to teach, especially if you don’t know our community,” he said.

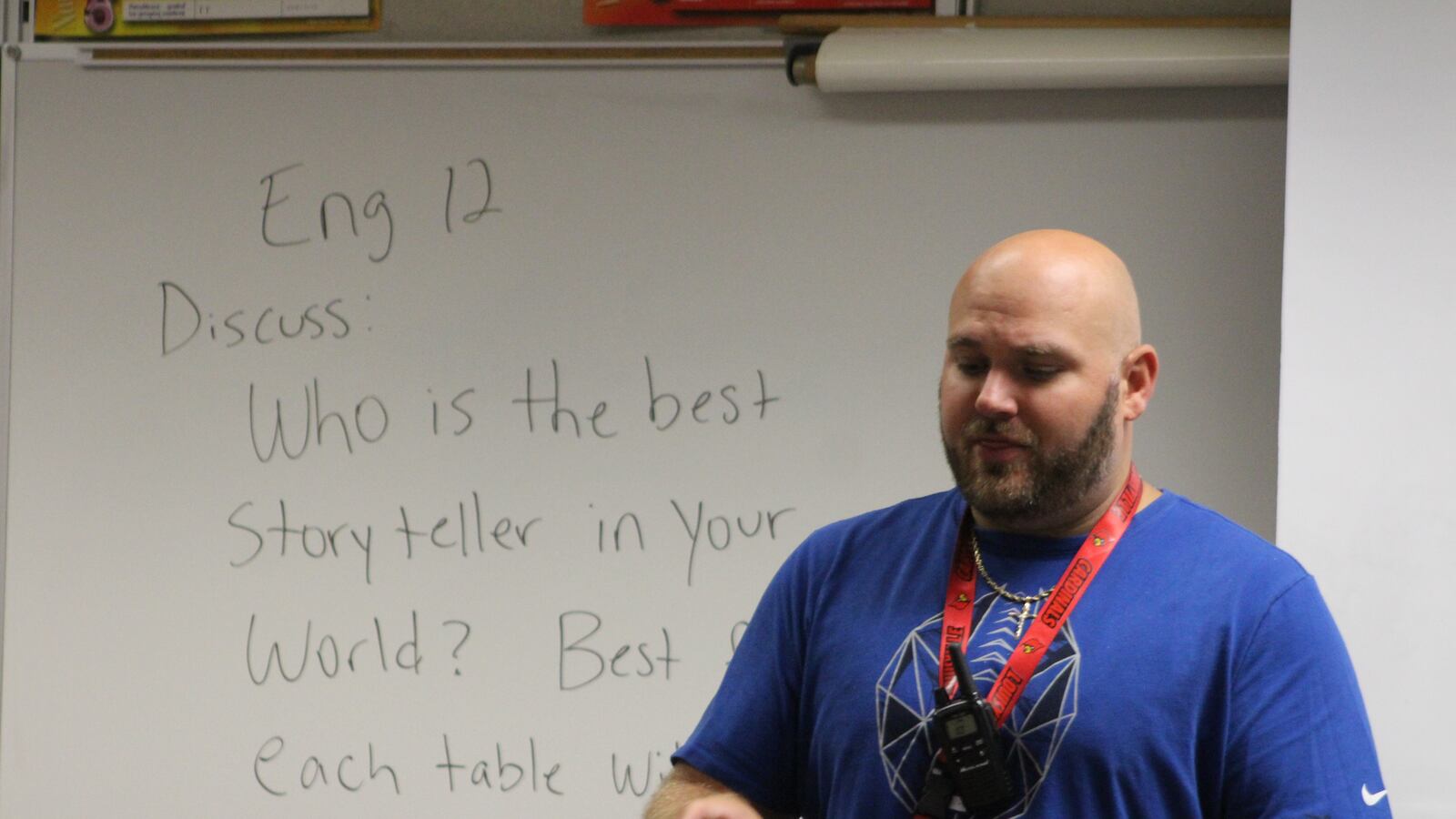

But for Brandon Stagnolia, Austin is home. An Austin High School graduate, he is now a teacher at his alma mater — and he makes students’ social-emotional needs a priority. For example, Stagnolia begins class each day by letting his 22 students know that what they say within these walls will remain confidential. “This is your safe place,” he tells them.

Even with the teachers helping promote well-being, face-time with their high school guidance counselor is still crucial, said Allen Hill, executive director of the Indiana School Counselors Association. That’s because school counselors receive specialized training that teachers do not.

“The amount of time [counselors] spend in direct contact hours with the student matters a lot,” Hill said, even if many school administrators don’t fully understand the role.

Jackson Snelling, an Austin High School senior who moved with his mother and brother from Kentucky 10 years ago, following the death of his father, said the teachers at Austin are committed to a culture of care – and they know how to support students who need it most.

“This would be one of the best schools in the state if it were recognized enough,” Snelling said. “It would be one of the best schools in the state if it had the financial resources.”

Snelling, 17, is on the autism spectrum, which, he said, can make learning and socialization challenging at times. But specialized attention from his teachers and counselors taught him how to manage his behavior and develop his passion for music.

It’s stories like this, of students rising above adversity, that motivates Brandon Stagnolia, the Austin High School graduate turned teacher.

“We’ve had students living in cars. We had a student enrolled last year who was living out of an RV at the Circle K down the road,” Stagnolia said. “We’re able to [rule] out a lot as teachers when our students know their classrooms are safe places.”