In high school, Ketrina Hazell often felt forgotten.

Several times, she had to stay behind during class trips because school buses could not accommodate her wheelchair, said Hazell, who has cerebral palsy. The school had no room for her occupational therapist, so they often met in the parent coordinator’s office, which was not outfitted with the necessary equipment, Hazell added. And she spent most days confined to a small, windowless special education classroom.

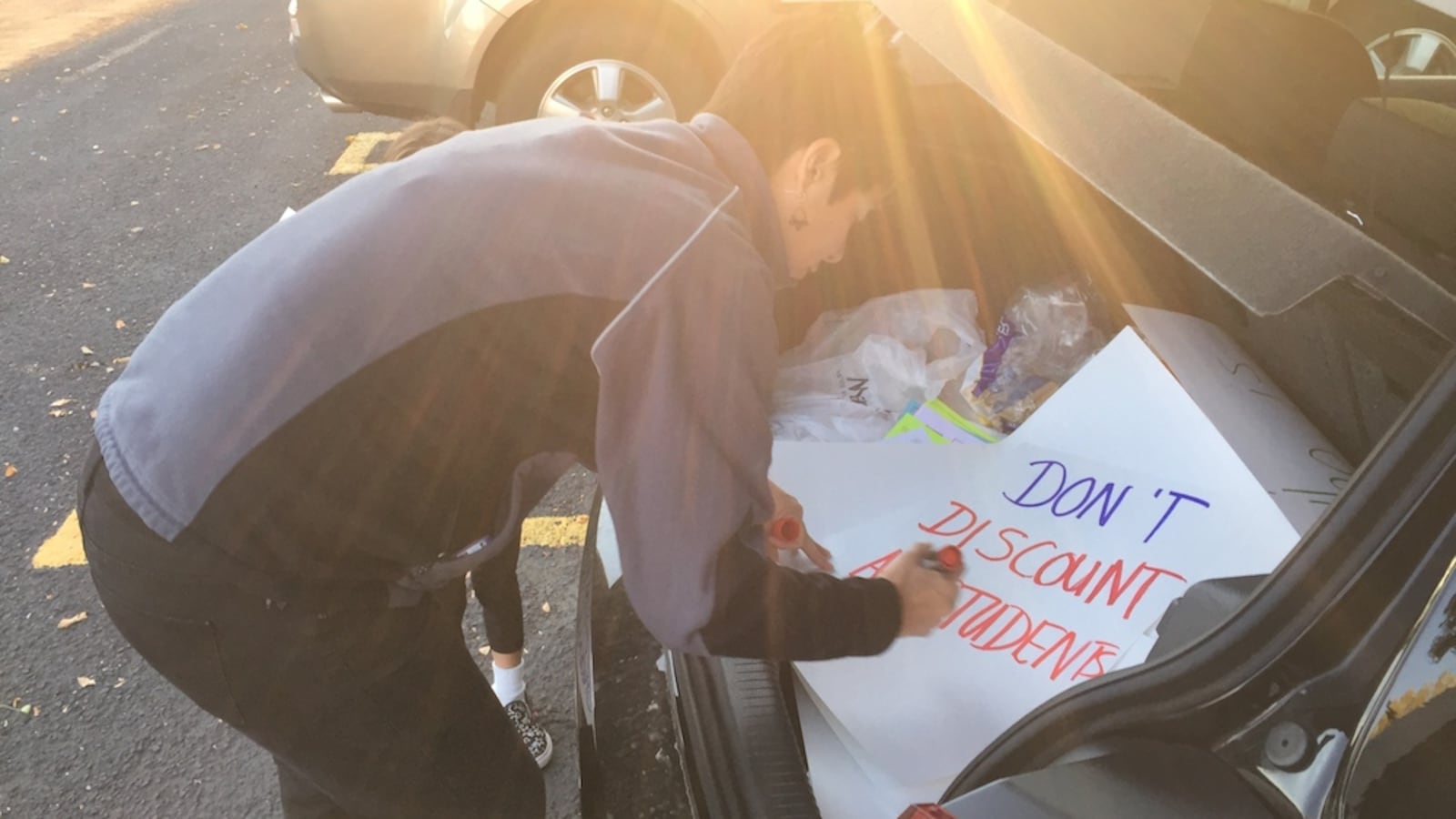

Eventually, she began to blog, post on social media, and even write letters to lawmakers and the mayor about the struggles of students with disabilities at her Brooklyn school, Teachers Preparatory High School. The advocacy netted some improvements, she said.

“We had to fight for everything we needed,” said Hazell, 19, now a first-year student at Kingsborough Community College. “It was never just given to us.”

Hazell could soon share her story with top state officials, as she is one of several students nominated to join a new panel that will advise the State Education Department’s special education office. The 10 to 15 current or recent high school students will discuss state policies relating to students with disabilities, and also share their recommendations and concerns.

The panelists, who will serve for two years, will be chosen from nominees submitted by advocacy groups and parent centers from around the state. Beginning this spring, they are expected to meet about three times per year, either in Albany or via videoconferencing.

The education department is convening the panel at a time of broad statewide policy changes that families and advocates say have been particularly burdensome for students with disabilities. The changes include schools’ shift to the Common Core learning standards and the transition to tougher high school graduation requirements.

“It’s an important contribution to our policy development and often the way we implement policies to have the perspective of students with disabilities,” said James DeLorenzo, the department’s assistant commissioner for special education. He said panel members would have the added benefit of honing their self-advocacy and leadership skills.

Students on the panel will get to advise education officials as the officials consider tweaking graduation rules for students with disabilities. In recent years, the state overhauled its graduation requirements, which included abolishing a special diploma for students with disabilities while still allowing them to earn lower scores on their exit exams. Advocates say that arrangement creates a two-tiered system and have called for diploma options for all students that require fewer state tests, which state officials are now considering.

Meanwhile, the state is continuing to roll out the more rigorous learning standards and accompanying exams, which many teachers and parents say have been especially challenging for students with disabilities. The state has said it will improve training for special education teachers and apply for a federal waiver that would allow some students with disabilities to take tests matched to their instructional level rather than their age.

Many families have heard about the new standards but are still struggling to understand what they mean for students with disabilities, said Revere Joyce, project coordinator of the parent center within the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled.

“That really hasn’t been fleshed out,” she said. “The Department of Education has a response, but it hasn’t really cut through to their understanding.”

Kathleen Boatwright, who nominated her son, Walter Douglas, for the advisory panel, said parents’ confusion stems from a communication breakdown between the state, city, individual schools, and families.

“There is such a communication lapse,” she said, adding that the panel could be one way to improve relations.

Walter, who is a freshman at Brooklyn’s Transit Tech High School, said that students with disabilities at his school often do not receive all the services stipulated by their learning plans, must attend unproductive group-counseling sessions due a lack of counselors, and sometimes endure bullying. He would like to share these concerns with the state, he said.

“I’m not looking for any award,” said Walter, 14, who has a learning disability. “I’m looking to help kids with disabilities who need help, just like I do, to be treated fair.”