School was always a struggle for Giselle Ruiz.

Ruiz grew up in Brooklyn and spoke only Spanish with her family at home. At school, though, she was expected to speak English, which meant she spent much of her childhood trying to translate between the two languages in her head.

“There was not one person who reached out to me, who said, ‘Ven acá, come here,’ which is what we do here,” she says.

“Here” is her classroom at P.S. 15 in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where Ruiz teaches in one of the city’s few bilingual pre-kindergarten programs.

For non-English-speaking families with preschoolers, bilingual programs remain few and far between, though the city is moving to rapidly expand both its pre-K offerings and dual-language programs over the next couple of years. Some parents and researchers are hoping the city combines those priorities to expand dual-language programs for its littlest learners. Until this happens, experts say, the city is missing an opportunity to teach bilingualism at an age when students’ brains are most adaptable.

Chancellor Carmen Fariña, a vocal proponent of bilingual education, has said the city plans to add or expand 40 dual-language programs in which students, usually of diverse linguistic backgrounds, learn English and a second language in the same classroom. Officials haven’t specified whether any of these will begin at the pre-K level, though, and the Department of Education does not include pre-K on its official list of bilingual programs in city schools. Department officials did not respond to repeated requests for current information about the number of bilingual pre-K programs.

That means the programs that exist are something of a citywide secret, though there is strong research on the educational power of those programs for young learners. Rutgers University researchers comparing pre-school age students’ performance in dual-language and English-only programs found that non-English speaking students in dual-language programs learned English just as well as peers who studied in English-only classrooms — without sacrificing their native language.

With little to no centralized information, parents looking for such programs have to do their own, often extensive, research. And interviews with teachers and experts suggest that even those with the time and wherewithal frequently come up short. Vanessa Ramos, a policy director at the Committee for Hispanic Children and Families, says parents often ask about dual-language pre-K programs, but she knows of very few in the public system.

“In some communities there are some private programs,” she said, “but not everybody can pay for that.”

There are several reasons growth in dual-language programs has lagged at the pre-K level. First and foremost, most schools don’t formally test preschoolers’ English proficiency until kindergarten. Schools do ask parents about their linguistic backgrounds and teachers often make their own more informal observations, and adjust instruction accordingly. But because pre-K students aren’t officially labeled “English language learners” by the Department of Education, they usually don’t get the same intensive language supports afforded to older students.

There’s also a shortage of teachers who, like Giselle Ruiz, are certified to teach both bilingual and early childhood classes. As schools continue to add pre-K classes under Mayor Bill de Blasio’s expansion, many schools are focused on getting full-day programs up and running, period, much less ones with bilingual instructors.

Anna Cano Amato, the principal of P.S. 110 in Greenpoint, says parents have asked her to open a dual-language pre-K class. The school already offers a French-English dual-language program in kindergarten through third grade, but pre-K classes — two of which just opened this fall — remain English-only. Though Cano Amato says she wouldn’t mind extending the dual-language program to pre-K, she felt there wasn’t enough time to hunt for a qualified bilingual teacher. Instead, the school offers an after-school French class for pre-K students.

At all grade levels, parental skepticism of bilingual classes has also played a role in limiting the model’s growth. Some non-English speakers want their children to learn English as quickly as possible, for instance, and shy away from bilingual instruction, fearing it will slow down English acquisition. Ruiz encounters this attitude often at open houses, and says she’s quick to denounce it by telling the story of her own, often difficult, schooling.

Meanwhile, the city has focused on providing all pre-K teachers with at least a small amount of training in supporting English language learners.

Carmen Colón, a Bank Street College of Education instructor who has been training new pre-K teachers since August, says students often ask for more coaching on how to teach children from different linguistic backgrounds. She suggests speaking slowly and clearly in class, repeating new words throughout the day, using hand gestures, inviting students’ families into the classroom, and asking parents to read with children in their native language.

Most pre-K teachers receive similarly broad training. Patricia Velasco, an early childhood education professor at CUNY’s Queens College, says that though most of her colleagues make a point of providing suggestions on how to help English language learners, only students who are studying to become bilingual teachers take required courses on the topic.

All of this could very well change as pre-K programs expand across the city and dual-language education advocates push to reach the city’s youngest learners. They point to the work of researchers from Stanford University, for example, who tracked the performance of about 18,000 English-language learners over 10 years. They found that, in the long term, Latino students in dual-language programs performed better on state standardized English tests than students in traditional English-only ones.

Velasco predicts a course on teaching English language learners could eventually become a state requirement for early childhood education teachers. And last spring, the state department of education included pre-kindergarten in a list of new guidelines for ensuring English language learners’ success.

What learning looks like in two languages

Dual-language pre-K programs do exist in New York City. Brooklyn’s P.S. 9, P.S. 15, and P.S. 46, and Manhattan’s P.S. 513 all offer similar programs. A typical classroom mixes about nine native English speakers with nine Spanish speakers.

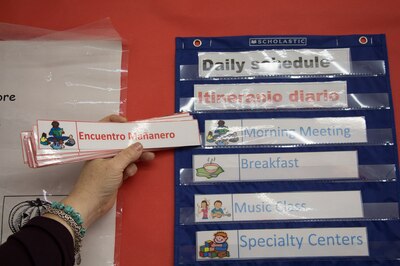

In a dual-language classroom like Giselle Ruiz’s, a bilingual teacher will spend roughly half of the day teaching in Spanish, and half in English. The bookshelves are well-stocked with texts in both languages, and classroom decorations include Spanish and English words side by side. Children are expected to interact and play in both languages over the course of the day, with the goal that everyone will become bilingual over time.

To help children distinguish between languages, teachers often turn to color cues. In Ruiz’s classroom, posters and other decorations always have English words written in blue font and Spanish ones written in red. One morning everyone spoke English, but as soon as Ms. Ruiz slipped on her red polka-dotted scarf after lunch, her students knew it was time for Spanish. Ruiz assiduously avoids slipping into Spanish unless the red scarf is on.

Dual-language programs often depend on this strict language division. But at the pre-K level, teachers say they try to stay flexible. After all, pre-K teachers work with four-year-olds who are not only new to language instruction, but to school in general.

Reina Garcia, a pre-K teacher at P.S. 46, says she starts each day in whatever language the class last spoke the previous day. This means she can continue an activity from the previous day if she feels like it deserves more time. Ms. Ruiz takes a similar approach. During a recent visit, when her students arrived back in the classroom after music class, they sang her a song in each language — even though it was English-only time. And if a child accidentally blurts out an English word during a Spanish-only activity, Ruiz does not admonish or correct the student.

Programs like the one where Ruiz teaches have emerged due to a combination of pushy parents and willing administrators. At P.S. 15, prospective parents raved about the dual-language experiences their children were getting in summer camps and school officials decided to start their program as early as possible.

The story was similar at P.S. 46, where administrators decided to change their transitional bilingual program into a dual-language one in response to parent demand. (Transitional programs, which have fallen out of favor across the country in recent years, ease students into English-only instruction over time.) Both P.S. 15 and P.S. 46 have also received grants, which the city still offers, to help fund teacher training and curriculum development for dual-language programs.

Class and socioeconomics may also have something to do with whether dual-language programs get up and running. As city officials have admitted, well-heeled parents from neighborhoods like Chelsea tend to clamor for them most loudly and aggressively. Though Queens has the highest percentage of English-language learners, it’s Manhattan that educates the highest percentage of them in dual-language programs.

Experts say one reason dual-language learning works is that children apply their knowledge of one language to another. Students also share skills with each other, Ruiz says, meaning something as simple as children arguing how to destroy a tower they’ve just built can serve as an informal language lesson.

“A giraffe will knock it down,” one of Ms. Ruiz’s students remarked one morning, holding up a toy giraffe. “No, today an elephant will knock it down,” another argued, waving his toy elephant. The tower won’t last, but for the native Spanish-speakers watching and listening to their English-speaking peers, the new vocabulary words could last a lifetime.

Madeleine Cummings is a fellow for The Teacher Project, an education reporting initiative at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism dedicated to covering the issues facing America’s teachers.