Facing budget pressure at home and from Washington, Gov. Andrew Cuomo proposed increasing school aid by 3 percent this year — far less than what advocates and the state’s education policymakers had sought.

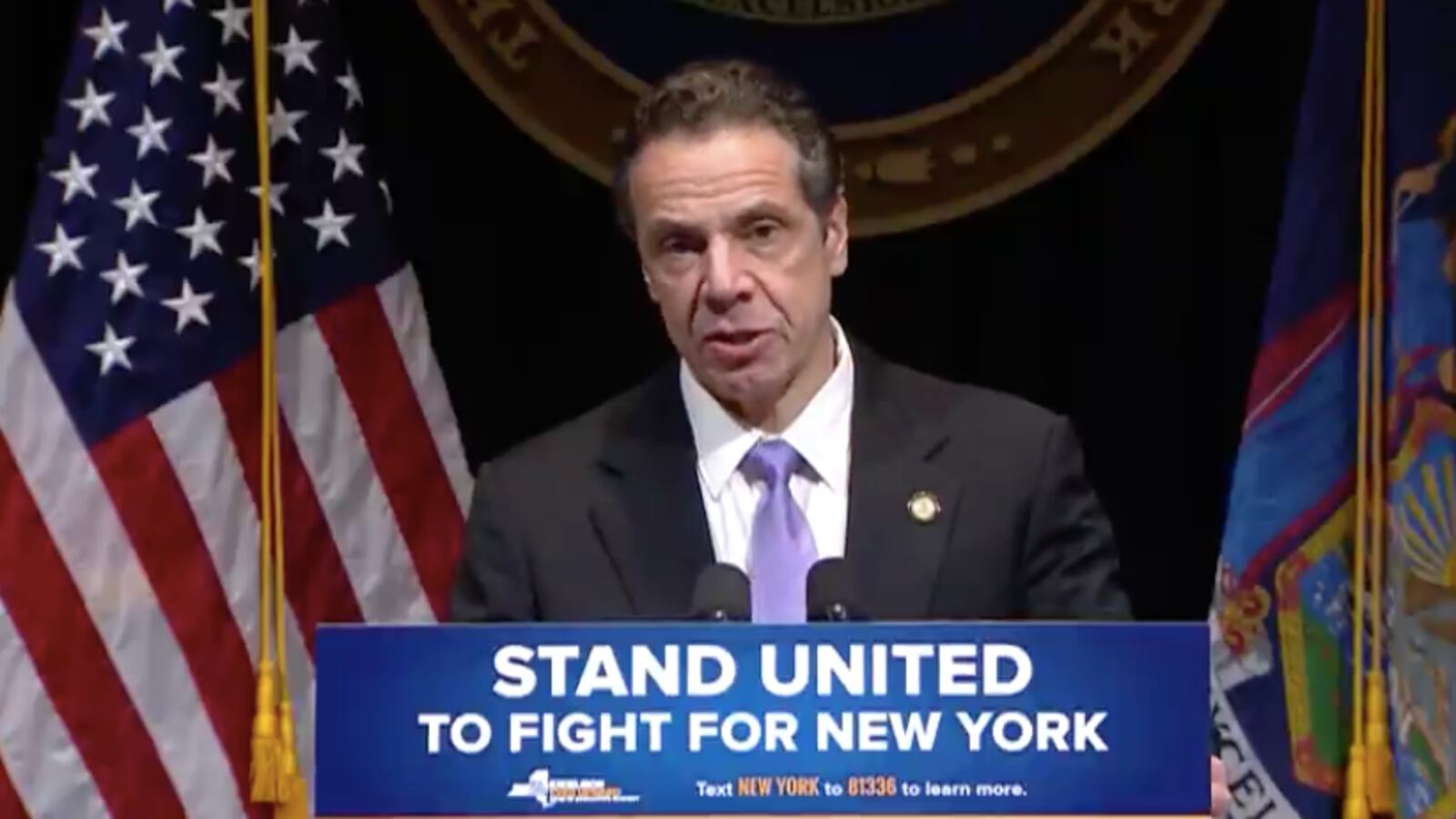

Cuomo put forward a $769 million increase in school aid during his executive budget address on Tuesday, less than half of the $1.6 billion sought by the state’s Board of Regents. In response, the state’s top education officials said they were “concerned,” and suggested that they would press lawmakers to negotiate for more education spending.

The governor’s modest increase in school funding comes amid a projected $4.4 billion state budget deficit, a federal tax overhaul expected to squeeze New York’s tax revenue, and the threat of further federal cuts.

Still, Cuomo, a Democrat who plans to run for reelection this fall and is considering a 2020 presidential bid, defended his spending plan as a boost for schools at a time of fiscal uncertainty.

“We have increased education more than any area in state government,” he said during his speech in Albany. “Period.”

He also floated a plan to have the state approve local districts’ budgets to ensure they are spending enough on high-poverty schools. And he set aside more money for prekindergarten, after-school programs, and “community schools” that provide social services to students and their families.

Now that Cuomo’s proposal is out he must negotiate a final budget for the 2019 fiscal year with lawmakers by April 1. While the Democratic-controlled assembly is likely to push for more school spending, the senate’s Republican leaders are calling for fiscal restraint and tax cuts.

What was the response?

Advocates and policymakers were alarmed by Cuomo’s proposed $769 million education bump — a 3 percent spending increase compared to last year’s 4.4 percent boost.

Last month, a coalition of statewide education organizations estimated that the state would need to increase spending by $1.5 billion just to maintain current education services. The group, which includes state teachers union and groups representing school boards and superintendents, called for a $2 billion increase.

In a statement Tuesday, Board of Regents Chancellor Betty Rosa and State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia noted that Cuomo’s proposal was less than half the amount they sought. They promised to work with lawmakers to ensure the final budget amount “will meet the needs of every student throughout our State.”

Anticipating such criticism, Cuomo noted in his speech that he has expanded education spending by nearly 35 percent since taking office. His proposal would bring total school aid to $26.4 billion — the largest portion of the state budget.

Still, that didn’t prevent pushback. A state assemblyman heckled Cuomo as the unveiled his education spending plan, suggesting it was not enough money.

“It’s never enough,” Cuomo shot back.

Will poorer schools get more funding?

Cuomo said he wants to fight “trickle-down education funding” and ensure that poor schools receive their fair share of cash.

To that end, Cuomo wants the state education department and his budget office to review local school district budget plans. The plan is aimed at larger school districts, including New York City, which Cuomo singled out in his speech.

“Right now we have no idea where the money is going,” Cuomo said on Tuesday. “We have a formula. We direct it to the poorer districts. But what did Buffalo do with it? What does New York City do with it?”

It’s unclear how the proposal would impact New York City, which already uses a funding formula designed to send more money to schools with needier students. But some education advocates were intrigued by Cuomo’s idea, which they said could be a way to expose and fight inequities in school funding across the state.

“Right now, school-level expenditure with consistent definitions is really a mystery,” said Ian Rosenblum, executive director of The Education Trust – New York. “It means that a lot of inequity can be swept under the rug.”

Cuomo officials also said that 73.1 percent of funding will be directed to high-needs districts in this year’s budget, which the state said was the highest share ever. Last year, they received 72 percent.

But advocates are more concerned with the state’s “foundation aid” formula, which funnels a greater share of funds to high-needs districts. The formula was created in response to a school funding lawsuit settled more than a decade ago; advocates say schools are still owed billions from the settlement.

Cuomo proposed boosting foundation aid this year by $338 million, a far cry from the $1.25 billion requested by the Board of Regents. Without more foundation aid, some advocates say Cuomo’s promise of greater funding equity rings hollow.

“Equity is you’re actually helping to lift up poor districts so that they can provide an equitable education,” said Billy Easton, executive director of the union-backed Alliance for Quality Education. “Not just that they’re receiving a larger share of a too-small pot.”

What does all of this mean for New York City schools?

New York City is not immune from Albany’s budget crunch.

The total increase proposed for the city — $247 million — falls about $150 million short of the mayor’s projections in November, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office.

It may also be difficult for the city to wrangle funding for big-ticket items. Mayor Bill de Blasio wants to expand his prekindergarten program to 3-year-old students, but he estimates that he will need $700 million from state and federal sources by 2021. (The governor proposed $15 million to expand pre-K seats across the state.)

How about charter schools?

Cuomo would boost spending for charter schools by 3 percent — the same rate as for district schools. He also wants to provide more support for schools that rent private space, which is a major financial burden for some schools.

“Once again, Gov. Cuomo demonstrated his unwavering commitment to ensuring every student in our state has access to a great public education,” said James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center.