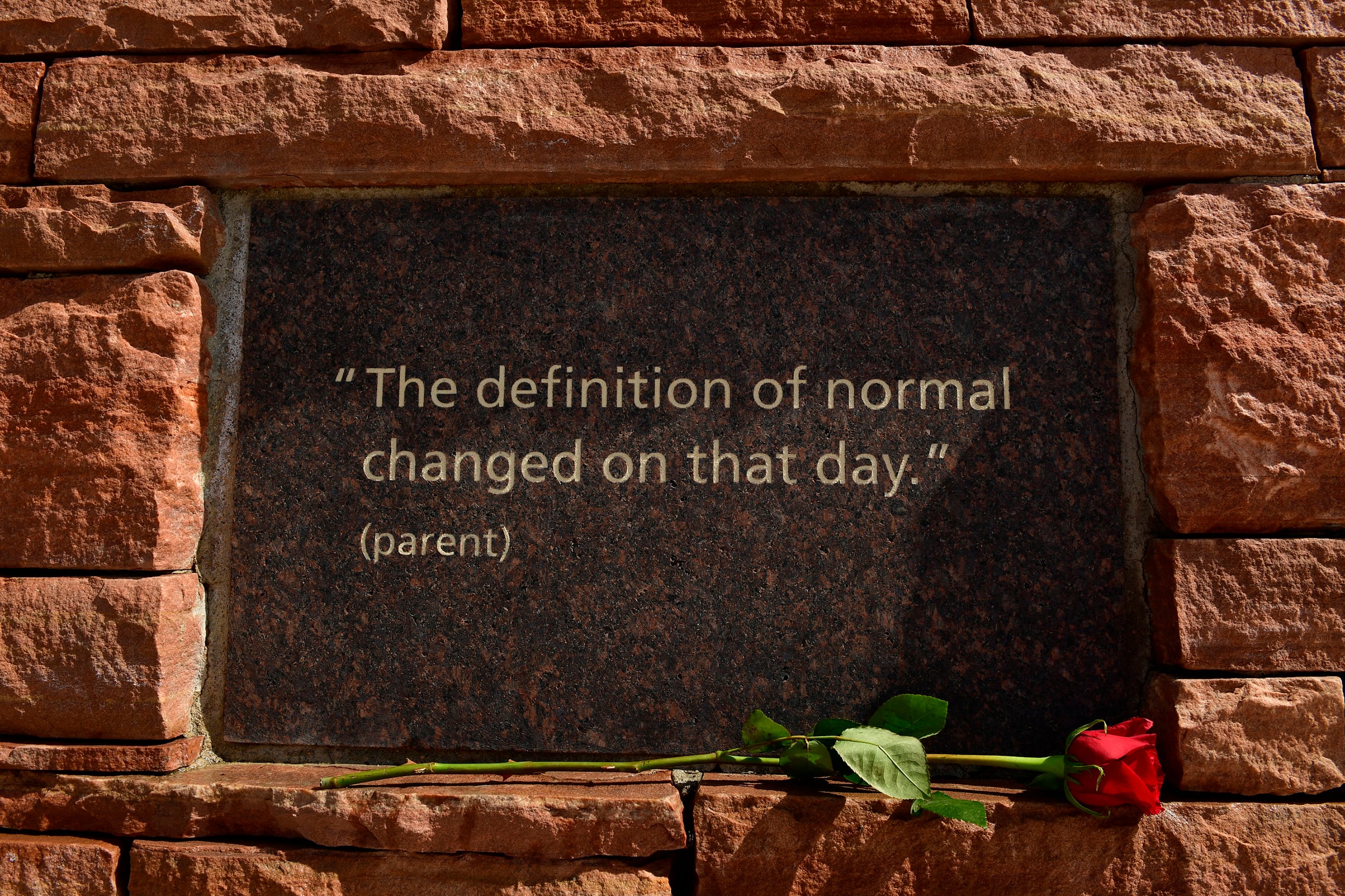

When Heather Martin was a senior in high school, she survived the Columbine High School shooting that killed 12 students and one teacher in Littleton, Colorado. Even as she tried to move on with her life, she carried the trauma of that day inside her — often in ways that surprised her.

The following year, during a community college class, she burst into tears during a routine fire drill, confused and embarrassed by her emotional reaction.

“I hadn’t remembered, until that very moment, that the fire alarm had been going off while I was barricaded for three hours before the SWAT team came,” she said.

She also struggled with panic attacks, an eating disorder, and insensitive comments from instructors. Eventually, Martin dropped out of college.

Today, Martin is a high school English teacher who prioritizes making her students feel safe and giving them the tools to understand and cope with trauma. She’s also the executive director of The Rebels Project, a nonprofit that supports survivors of mass tragedy. In March, she attended the State of the Union address as a guest of U.S. Rep. Jason Crow, a Democrat who represents the southeastern Denver suburbs.

Martin, who teaches at Aurora Central High School, talked to Chalkbeat about how she rediscovered her desire to teach after leaving college, what calming techniques she teaches students, and why she loves home visits.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

When I was in elementary school, my friends and I used to “play school” when we would study for tests. We alternated being the teacher, and I think that really laid the foundation for me wanting to teach in some way.

After the shooting at Columbine in 1999, I struggled a lot with trauma while attending community college and ended up dropping out. One day, while filming some B roll for a documentary called ”Grieving in a Fishbowl,” I was asked to flip through my high school yearbook. I found where my English teacher had signed: “I hope you major in English and become a teacher - your students would love you!” it read.

It seems I had forgotten for a while where I wanted to go, but I eventually found my way back. After 10 years and a long road of healing, I went back to school, finished my degree, and earned my teaching license.

How did your trauma manifest during your initial college experience?

I had extreme anxiety and unpredictable panic attacks — or at the time I thought they were unpredictable. I developed an eating disorder, started ditching and failing classes, and even tried recreational drugs. I attributed many of these things to “normal” college behavior and refused to acknowledge that it had anything to do with the shooting. I told myself, “It’s been ___ months, I should be fine.”

I had an English teacher assign a final essay that had a prompt related to school safety or guns in schools. When I finally worked up the courage to tell her why I couldn’t do the essay, she said it was required and if I didn’t do it, I would fail the class. I never went back to that class and, ultimately, ended up failing. I was already questioning my “right” to be traumatized, and her dismissal was extremely harmful.

When I took English again, I was assigned to write a 2-3 page personal narrative about an event that impacted me. This was about a year after the shooting, so I decided to actually tackle writing about it. I wrote upwards of 10 pages. On the due date, I printed my essay and brought it to the instructor. I told her how long it was, but I did not tell her the content. I wanted reassurance that the length was okay.

She said she would probably just grade me on the first few pages. Again, I felt dismissed and that my experience didn’t matter, and again, this amplified my questions about whether I had any right to feel and be traumatized. Again, I failed English class because I stopped attending.

My students love to hear that I failed English class twice in college!

What was it like to attend the State of the Union address?

The invite from Congressman Crow came as a surprise and I was very excited, and even a bit nervous, to attend. Every person I met was very interested and compassionate regarding long-term recovery from trauma. Congressman Crow and his staff were wonderful and did an excellent job of helping get the message out about the need for long-term support.

How did your own experience in school influence your approach to teaching?

I was a student who often felt like I wasn’t seen or noticed in school. I did just enough to stay off everyone’s radar — never a super-high or a super-low performer. As a teacher now, I look for students who may feel like I felt and am sure to connect with them as best I can. Also, obviously, the shooting and my subsequent healing journey help to drive my mission to make my classroom (and school community) as safe as I can — both in the physical sense and the emotional sense.

Tell us about a favorite lesson you teach.

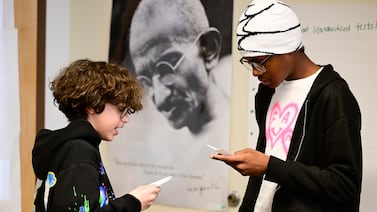

I call it a “Mirror Poem.” We begin by comparing Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130, “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” to Sonnet 18, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” We focus on which is the “truer” love poem.

After many discussions, we decide which one represents a mirror. The answer always depends on what students view as a mirror’s purpose, so the responses are excellent. My favorite part is that after we read and analyze, students write their own poem using a mirror as a metaphor to describe how they see themselves and/or how others see them. The poems are INCREDIBLE and reading them never ceases to amaze me at how brilliant they are.

Tell us about The Rebels Project.

I co-founded the organization in 2012 with three other classmates from Columbine in the aftermath of the Aurora theater shooting. It’s named for the Columbine High School mascot. We wanted to provide support that we didn’t have access to after the shooting at our school — a space to share, connect, and heal alongside others who understand what it’s like to experience a similar event. Everybody on our leadership team has experienced a mass trauma themselves, which drives our decisions in every project we develop.

We connect survivors from all across the world. We hold support meetings, travel to impacted communities, educate the public on ways to support trauma survivors, and host an annual survivor retreat. We do this all as volunteers.

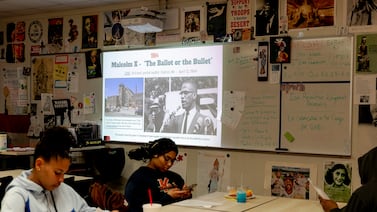

How do you incorporate trauma-informed practices into your classes?

Recently, we read ”The Kite Runner,” which has some disturbing content that may provoke some anxiety or trauma responses. We practice grounding techniques before reading, then I offer opportunities to use some of the techniques as we read. These can include coloring, folding origami, deep breathing exercises, and bilateral movements that use both sides of the body together, such as tapping, pacing, or walking.

Another way I practice this is through good old-fashioned modeling. I point out when I’m feeling activated, how I notice it, what it feels like, and how I ground myself. I’m also very open about my healing journey. I teach seniors, so it’s age-appropriate that I share my story about surviving a school shooting and how I struggled in the aftermath. I am honest about some of the struggles I still have, even 25 years later. I think it’s so important that they know that healing doesn’t always mean you “get over it,” it’s more about working through it. Experiencing trauma changes us, and I feel that acknowledging that change is important.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

At our school, we conduct home visits to help connect with the parents and guardians. These are always positive — basically pumping up the kiddo and sharing how amazing they are. I’ve had such wonderful visits with parents who come from various countries around the world, including Afghanistan, Republic of the Congo, Mexico, and Burma. I absolutely love connecting with them and learning more about the lives of the students.

What are you reading for enjoyment?

Currently, I’m reading a few books. (Yes, I’m one of those weirdos that can read multiple books at a time!) They include ”The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” by James McBride, the ”Skyward Series” by Brandon Sanderson, and Bruce Springsteen’s memoir, ”Born to Run” because he is MY FAVORITE!

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.