This post has been updated, as of January 4, 2018, to add the names of our design team members and to reflect our final Teach-Off design.

Two years ago, SXSW EDU approached me to be the keynote speaker at their conference in Austin, Texas. My book, Building a Better Teacher, had come out the year before, and they wanted me to talk about it. I floated a counter-proposal: Instead of having me, a journalist, stand on stage and talk about teaching, what if a teacher stood on stage and actually taught?

The idea stemmed from my reporting in Japan, where I watched public research lessons — complete lessons taught before an audience of fellow teachers, and followed by a discussion of what could be learned from the teaching episode. Public lessons are common in Japanese schools, part of the larger practice of jugyokenkyu, or lesson study. I absolutely loved observing these lessons and the discussions afterward. Each one was a gripping drama packed with confusion, struggle, and moments of revelation. I had already begun to see teaching through new eyes when I traveled to Japan — not as a matter of charisma and personality, the common American understanding, but as a craft — and these research lessons built on, and deepened, that lesson.

As I wrote in my book, “Teachers not only had to think; they had to think about other people’s thinking. They were an army of everyday epistemologists, forced to consider what it meant to know something and then reproduce that transformation in their students. Teaching was more than story time on the rug. It was the highest form of knowing.”

How amazing would it be if I could find a way for other Americans to have that same experience I had, learning, anew, what teaching is all about, without traveling to Japan? Alas, SXSW EDU said no to my proposal, but the organizers kept the door open to showcasing live teaching at a future conference. Two years later, when we discussed the idea again, they said they wanted to pursue it, and the seeds of our Teach-Off experiment were planted.

The original idea was Iron Chef, for teachers. That came from Akihiko Takahashi, a professor of education here in the U.S. who spent his early career in Japan, and a champion for bringing lesson study to America. Takahashi told me about a twist on the public research lesson, inspired by Iron Chef, in which two teachers teach live lessons back to back — each tackling the same topic, but through a different approach, like chefs cooking the same set of ingredients to different effect. As I wrote about in an excerpt of my book for the New York Times Magazine, he’d participated in such a “teach-off” on a stage in front of 1,000 teachers.

"I absolutely loved observing these lessons and the discussions afterward. Each one was a gripping drama packed with confusion, struggle, and moments of revelation."

If I wanted to give more people the learning experience I had, and do it in the U.S., the Iron Chef approach seemed perfect. But as my colleagues at Chalkbeat and I began talking with SXSW EDU about how we could actually pull such a thing off, we realized it would be all but impossible, at least this year.

Critical to lesson study is that a teacher teaches his or her own students. That way, he knows what the students do and don’t understand before going into the lesson. And it honors an essential truth of teaching: that each lesson is just one page in the long book of a year or more’s worth of learning. Flying two teachers and their students to Austin, and all the legal and logistical work that would require, seemed beyond possible to us in the time we had. But SXSW EDU was a big stage, and we didn’t want to turn the opportunity down without considering: Might there be a more doable version?

As we were thinking about this, I happened to attend a day of lectures and discussion honoring the career of Magdalene Lampert, a master teacher educator who was also, along with Takahashi, a main character in my book. Lampert has dedicated her career, in part, to explaining the complex nature of teaching within the over-simplified culture of American public policy. In the last several years she had hit on a concept that colleagues of hers were using in teacher education: the instructional activity, a classroom routine that can be used with students — and also, crucially, practiced (“rehearsed,” in her words) in lower-risk settings without actual students, like a teacher education classroom where fellow students play the part of children in a class.

At the center of the event honoring Lampert, held at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, was a demonstration of an instructional activity, also known as an instructional routine. In the demonstration, Elham Kazemi, a professor of math and science education at the University of Washington, led a group of adults in an instructional activity called “choral counting,” while Lampert acted in the role of teacher educator, offering feedback to Kazemi as she walked us through the activity.

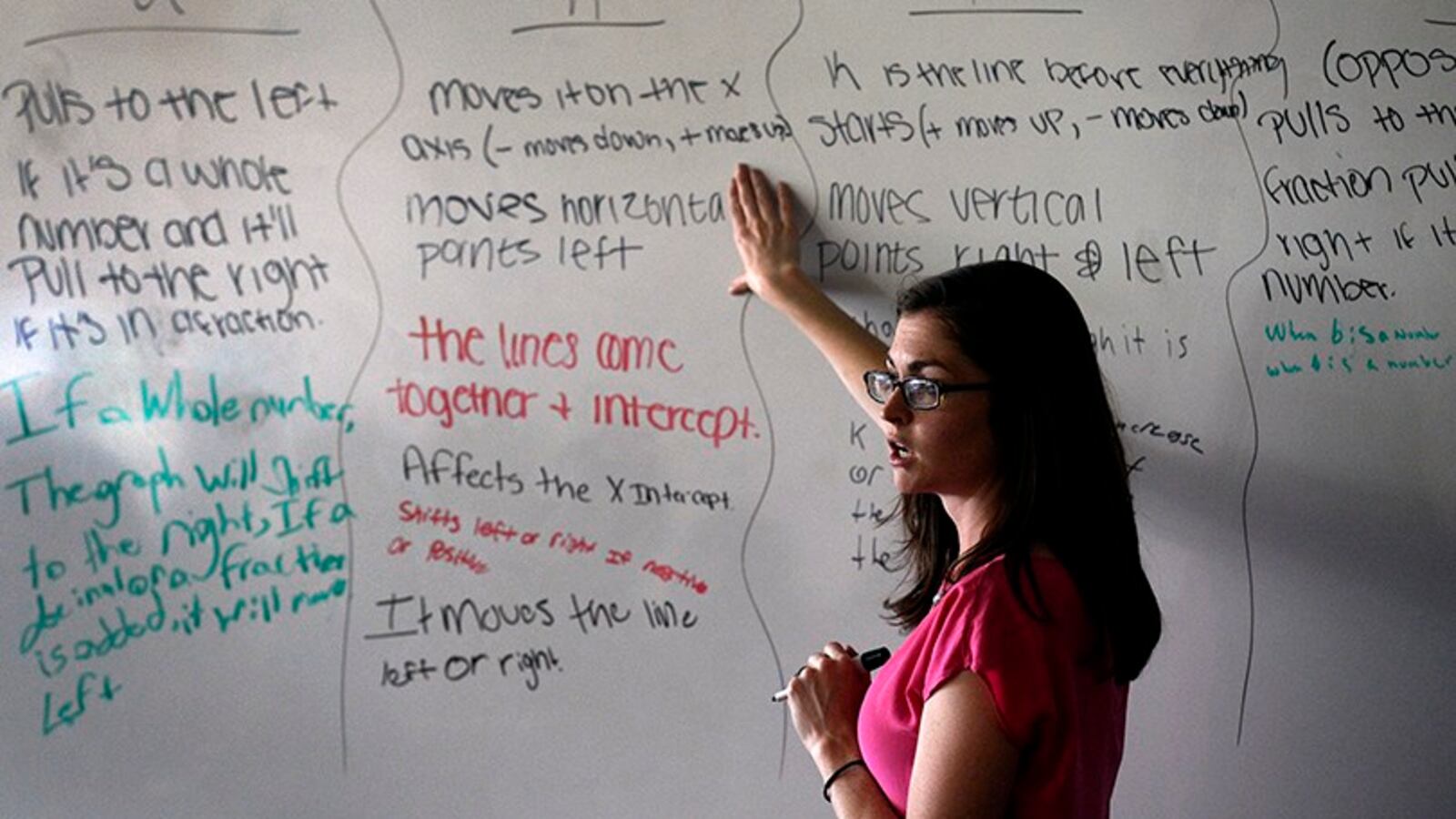

Everyone in the room was riveted: by the lesson, which had us counting by 7’s and looking for patterns, and also by the teaching, which Lampert and Kazemi unveiled together, vividly, showcasing the many decisions Kazemi had to make, from how to organize the numbers on the whiteboard to help us see the patterns to how to design the activity and how to respond to our questions. This work is almost always invisible to the general public, but via the instructional activity, Lampert and Kazemi taught us two lessons — the first about math and numbers, and the second about teaching. I had the same feeling I did during public lessons in Japan: a gripping reminder of how complicated, challenging, and awesome teaching can be.

Afterward, I talked with some of the other attendees about our SXSW EDU opportunity, and an incredible group was formed. I called them our “design team” — teacher educators who thought there had to be a way to work within the constraints of our limited budget and timeline to teach a broader audience something important about teaching. One member of the group told me about her long-standing fascination with cooking and singing competition shows: how they showcased an intricate craft to a broad audience (the broadest!). She’d long thought, in her private time, about how a similar show might work for teaching. In a way, that was already part of her job as a teacher educator, helping novices come to unlearn their starting-point assumptions about teaching and see the work in a new, more complicated, and more truthful light.

When we all left Cambridge, I asked this design team to join me and our executive editor for a series of phone calls to determine if there was a way we could achieve our goals within the context we had been given. It wasn’t lost on me that the challenge we presented our design team with was not unlike what teachers have to do every day: work within far from perfect settings to achieve a learning goal that can sometimes feel impossible, given the constraints. Unsurprisingly, the design team stepped up brilliantly, and the Great American Teach-Off was born.

We’ll share more soon about how the competition is aimed at working within constraints. A few of the problems we sought to solve and our solutions to them:

How could we approximate some of the most important work of teaching in a condensed amount of time?

The concept of an instructional activity is a huge help here. Think of the instructional activity like a very well chosen book excerpt. It’s impossible to convey the fullness of a book without actually reading it, but a great excerpt can take a slice of what it feels like to read the book. By using instructional activities for our lesson challenge, we realized we could show the complexity of teaching in a period of time much shorter than an average lesson.

How could we approximate teaching without actual students?

This is a huge constraint, but it is also one that teacher educators have worked hard to solve for, and we decided to borrow from what they have learned. While some purists believe teaching can’t be taught until a teacher has a classroom all his or her own, others take the position that it’s important to give people who are learning to teach experiences that are, in their words, “approximated” versions of the real thing before they become full-blown teachers.

Both Lampert and Pam Grossman, dean of of the University of Pennsylvania’s education school, have shown that teachers can learn about teaching when their colleagues act in the role of students. Kazemi and Lampert’s instructional activity at Harvard, meanwhile, showed me that even with a large audience of adults acting as students, many important parts of teaching could still be made visible. The crucial and essential work of understanding students’ developing thinking over the course of a year cannot be directly seen, but with a solid discussion afterward of what the slice of teaching shows us, it does not fully disappear. We’re building on these models as we design the Teach-Off.

How could we make the invisible work of teaching visible in a contest setting?

Since making the invisible visible is, well, our entire goal here, we knew we couldn’t just have a contest in which teachers taught live on stage. We also needed lots of opportunities to help the audience peer inside teachers’ heads and see what thinking they were doing as they taught. Cooking and singing competition shows offered some great models for how to do this in the form of the celebrity judges, the “coaches” who sometimes are assigned to contestants offstage, and the host who interviews everyone about how they are making their decisions. We decided that our Teach-Off would include all of these roles: a coach for each team of teachers, judges who are skilled teacher educators and would understand that their role was not to critique but to unpack and help the audience “see” the teaching, and finally a host who could interview not just the judges but also the teachers themselves about how they tackled their lesson challenge. (Sidenote: We haven’t identified people to fit all these roles yet, so if you’re interested, please let us know!)

Is a competition appropriate? [UPDATED January 4, 2018]

We wrestled with this a lot, and ultimately our revised design eliminates the competition element. There won’t be a winner of the Teach-Off, only prizes that a panel of judges award to each participating team.

Some have speculated that we faced pressure from sponsors or some other force to make the Teach-Off competitive. We didn’t. We were attracted to the format because of the narrative power a contest holds for an audience. The stakes of being anointed the “winner,” or not, would have been completely made-up, but we hoped they would also make people keep watching.

Nevertheless, as we saw many teachers recoil at the thought of a competition, we decided the narrative stakes were less important than what was always our ultimate goal: to showcase the way that teachers plan, re-plan, re-think, revise, both beforehand and on the spot, and to honor that work with all the force we can muster. As I said in the earlier version of this post, if we pull this off, the real winners won’t be either team of teachers. They’ll be the audience and the general public, who will learn what it takes to engage in the professional practice on display.

We’re still finalizing the design of this event in real time, and surely we don’t have this in its best possible form just yet. We welcome discussion of what it takes to make the work of teaching public. And we also offer deepest gratitude to SXSW EDU and the philanthropists who made it possible for us to take up this opportunity in the first place. I especially want to thank our design team: Julie Sloan of the Boston Teacher Residency, David Wees of New Visions for Public Schools, and Amy Lucenta of Fostering Math Practices. These teachers and teacher educators have donated a lot of time and thoughtfulness to making this a success, and their generosity of time and spirit inspire me.

A final footnote: If you want to watch the keynote address I ended up giving at SXSW EDU in 2015, I am embarrassed to report that you can do so online, here. You’ll see I tried to act out teaching on stage, my best approximation of the learning I’d had and probably one of the worst acting performances you’ll see. I think we can do better, and in March — with the help of all of you — we will try.