Appreciation is nice, but isn’t recognition better?

In honor of Teacher Appreciation Week, I want to reprise some of the strongest voices we’ve showcased in Chalkbeat so far this year: those of teachers. Nobody can tell the story of American education better than the people who create it every single day.

That was certainly the case for the following four teachers, who volunteered their time and, more importantly, their wisdom when they contributed to Chalkbeat’s reporting over the past year.

So here’s an idea: Thank one of them — or a teacher you know yourself — by making a donation to Chalkbeat in their honor. It’s a double-whammy kind of gift, because it’s easy (just click here) and meaningful (proceeds will go toward supporting our ability to tell more teachers’ stories in the months to come). We’re also sending an extra gift to the first 10 teachers to be honored, courtesy of our sponsor Yoobi, the very cool school supplies company. (By the way, check out their tear-jerking thank-you to teachers this week.) Plus, we’ll feature some of the honored teachers on Chalkbeat.

Oh, and one more thing: Thanks to a generous $10,000 matching gift from Rick Smith, one of my own incredible teachers, every donation will be doubled. (Rick was the longtime editor-in-chief and CEO of Newsweek, and I’ve learned a lot from him about leading a journalistic enterprise.)

Now, on to the teachers.

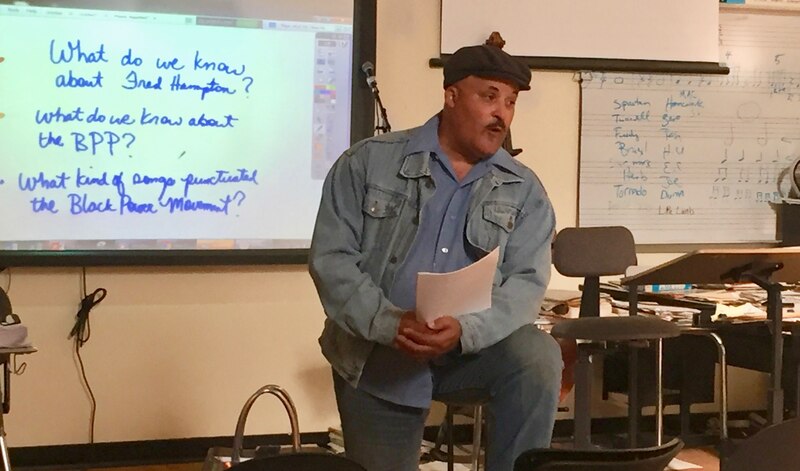

Quincy Stewart

We featured Quincy Stewart of Detroit’s Central High School because of his distinctive approach to teaching music, which blends African-American history with music theory. But it was the way he described a quintessential American teacher experience — being subject to policies outside your control — that made him unforgettable.

“It’s kind of like being…at the bottom of a latrine,” he said. “The biggest thud from what comes into the latrine lands at the bottom… Us teachers have really felt the thud of the crap.”

Sable Otey

Lately, whenever I push myself to add a workout into my busy day, I think of Sable Otey. For the last year, Otey would teach for a full day at her Memphis elementary school — and then spend a second full day training for the Olympics.

She told us how she found her motivation: “I realized I have been an inspiration to so many people, so many kids, so many adults, even, in my community. Just coming from Binghamton, being told some of the things that some of the kids are being told now — that they’re not going to be anything. They’re not going to get a college degree. I’ve overcome all of those obstacles.”

When students share their challenges with her, she tells them her own life story. “I think it’s my job to do that because it’s a village. Back when villages were raising people, a village actually raised me: my principals, my teachers, people in my community. All of those people helped me become who I am today.”

Ilona Nanay

You know “driveway moments,” when you stop what you’re doing to finish listening to a great radio story? I had one of those when I read teacher Ilona Nanay’s account of the pang of sadness she felt at her Bronx high school’s first-ever graduation ceremony. She was reading the graduation program, and all the students had notes next to their names sharing the college they planned to attend in the fall — except for two.

“These young women started high school as English learners and were diagnosed with learning disabilities. Despite these obstacles, I have never seen two students work so hard,” Nanay wrote. “By the time they graduated, they had two of the highest grade point averages in their class.”

“It would have made sense for them to be college-bound,” she continued. “But neither would go to college. Because of their undocumented status, they did not qualify for financial aid, and, without aid, they could not afford it.”

Jose Romero

I’m reserving this last entry for the person whose story gave me the most goose bumps. Jose Romero, a high school senior in Queens who is Mexican American, wrote about the perils of spending the first decade of his education never having a teacher who looked like him.

He framed his moving and beautifully written piece around two stories.

The first is of a moment in fifth grade when a classmate asked him whether he crossed the border from Mexico. Romero didn’t, but both of his parents did. Theirs is a powerful story of hope, challenge, love, and fate — and one that his classmate, sadly, never got the chance to hear. When the question came up, the classmate mixed it with a degrading slur about immigrants, and instead of creating an opportunity for sharing and learning, the boys’ teacher let the slur pass and shot down any further conversation.

The second story Romero tells is of his high school, the first place he’s ever had a teacher of color. He’s now part of an all-male mentorship group led by two African-American teachers. “It’s hard to explain the way it feels to have a teacher who looks like you,” Romero writes; “they’re like older brothers who become a huge part of our lives, even if it’s just for four years. They make it easier to connect and socialize and help me feel more like I belong.”

Here’s the part that gave me goose bumps: Romero’s own plan for the future is to pay his mentor teachers’ gift forward by becoming a fifth-grade teacher himself.

Special thanks to our partners at Yoobi for supporting this campaign.