Students who attended a KIPP middle school a decade ago were 13 percentage points more likely to enroll in college as a result, according to a new study of the country’s largest nonprofit charter school network.

KIPP cheered the results. “We made a commitment 25 years ago to help students climb the mountain to and through college, and these numbers show that we are moving closer to delivering on that promise on a national scale,” CEO Richard Barth said in a statement.

But the study can’t definitively say whether the charter network had an effect on students actually staying in college, and not enough time has passed to draw conclusions about college completion.

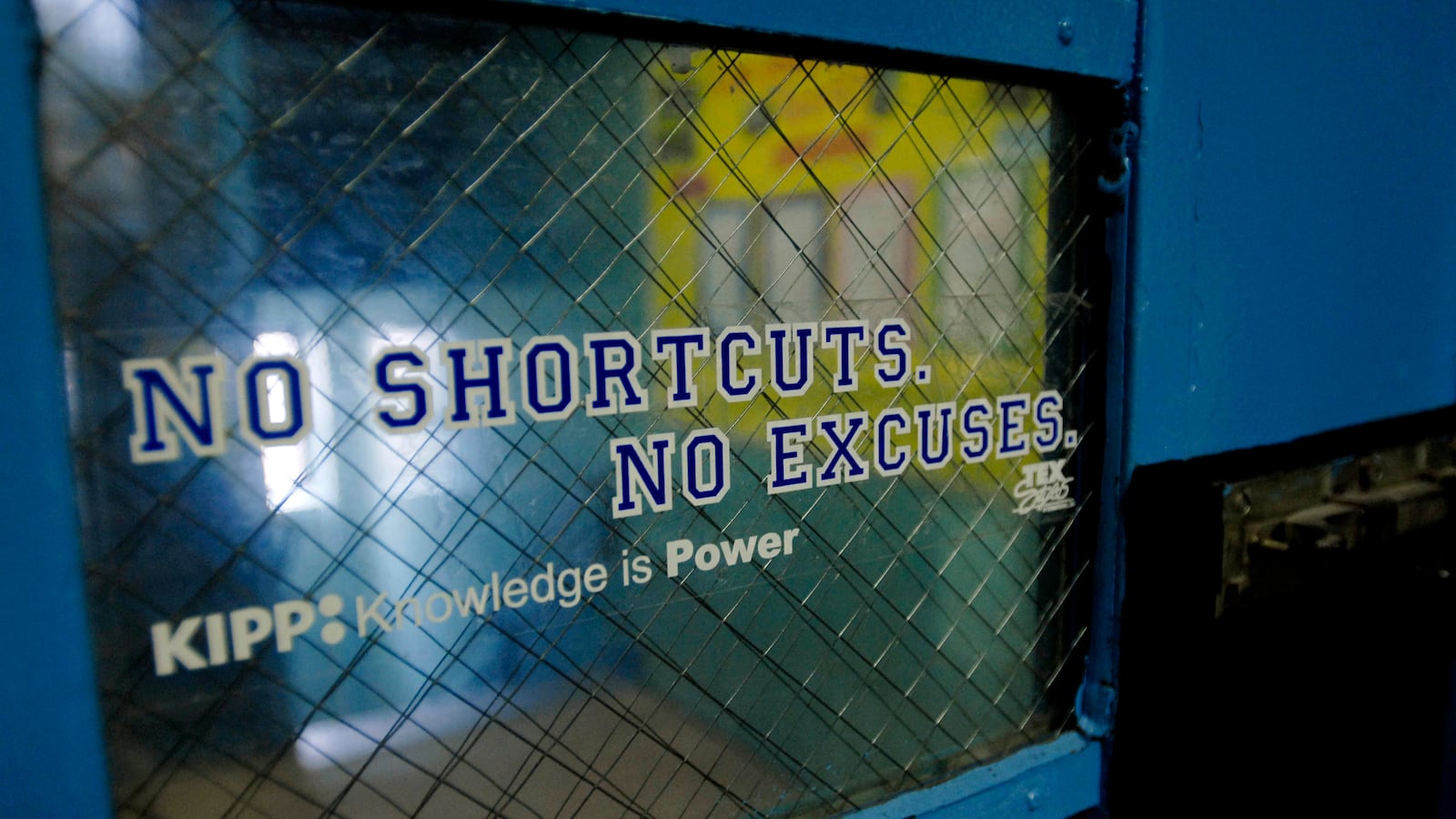

It’s the first rigorous attempt to measure the longer-term effects of KIPP, which pioneered an influential, much-debated “no-excuses” approach to running schools largely for low-income black and Hispanic students. KIPP, which just celebrated its 25th anniversary, now has 242 charter schools across the country in its network and recently won a large federal grant to continue growing.

The latest study builds on a 2013 paper that looked at about 1,000 students who applied to a KIPP middle school in 2008 or 2009. The initial research found that students who won the lottery had substantially higher math scores two years later compared to students who lost the lottery. (Other studies of KIPP have also shown that its schools produce large test score gains.)

The researchers continued to follow those students for this latest study. Attending KIPP, they found, had a large effect on four-year college enrollment: 52% of KIPP students enrolled in a four-year college within two years of completing high school, compared to 39% of those who didn’t go to KIPP.

That’s a big boost, comparable to the national gap in college enrollment between white students on the one hand and black and Hispanic students on the other.

But when the researchers looked at whether students remained consistently enrolled in college for four semesters, the KIPP advantage was less clear. Of the KIPP alumni, 33% persisted in four-year college, compared to 24% of the non-KIPP alumni. That 9-point difference was not statistically significant, which may reflect the study’s small sample of students but also means the researchers can’t say with confidence that KIPP made a difference.

The study focuses on students who entered a KIPP lottery at one of 13 middle schools; many also attended a KIPP high school. The authors estimate that each year at a KIPP middle or high school boosted four-year college enrollment by 2.5 percentage points and persistence by 1.7 points. (Again, the difference in persistence was not statistically significant.)

“For the students in this study, it is too early to say whether the strong effect of KIPP middle schools on college enrollment will ultimately improve rates of college graduation or lead to long-term improvements in employment and earnings after college,” write Thomas Coen, Ira Nichols-Barrer, and Philip Gleason of the research firm Mathematica. (The paper was funded by Arnold Ventures, the philanthropic arm of Laura and John Arnold; Arnold Ventures is also a funder of KIPP and Chalkbeat.)

But the authors say there’s reason to be optimistic.

“If a future study revealed that KIPP middle schools ultimately do have an effect of approximately 9 percentage points on college completion, that effect would be equal to more than a third of the degree-completion gap for black and Hispanic students,” the researchers explain.

This is a big “if,” though, since the study shows that KIPP’s college edge deteriorates after high school graduation, from a 13-point enrollment advantage to a 9-point edge two years in. That suggests that some KIPP students who are induced to attend college are dropping out without a degree and potentially with student debt.

KIPP leaders have spoken candidly about the challenges that many of their alumni face in college. In one survey of alumni, over 40 percent said that while in college they often or sometimes skipped meals for financial reasons. KIPP offers college advising services to alumni and, in some regions, emergency cash grants.

The study doesn’t show what aspect of KIPP’s approach — say, its college-going focus or its academic program — led to increased college enrollment.

It’s also possible that the results partially reflect other advantages KIPP has over nearby district schools, including the ability to spend more thanks to private fundraising and no requirements to replace all students who leave mid-year, minimizing one type of disruption. (Researchers have shown that students do not depart KIPP schools at higher rates than nearby district schools, rebutting a common criticism.)

KIPP is one of the largest charter school networks in the country, but it’s still only a slice of the charter sector writ large. Indeed, a recent national study of 31 charter middle schools — which tended to serve a more affluent student body than KIPP — found that they had no effect on college enrollment or persistence.

But KIPP has been a key model for the “no excuses” style of charter schooling, a somewhat disputed term which generally means high expectations, strict disciplinary standards, and an extended school day. (KIPP has said that it is moving away from aspects of this approach, including embracing restorative justice-style discipline.)

“No-excuses” charter schools have been shown to substantially raise test scores, but some critics have argued that these gains are unlikely to translate into long-term success, particularly after students leave such such a structured environment.

The latest study offers another data point, but the jury remains out.

Studies of the Noble charter network in Chicago and of “no-excuses” schools in Texas, including two KIPP schools, have found that such schools increase both four-year college enrollment and persistence. But a preliminary study in Boston — whose charter schools have been shown to dramatically raise test scores and four-year college enrollment — didn’t find clear evidence that charter students were more likely to complete a college degree.

“A growing body of lottery-based evidence shows that charters that boost test scores also boost enrollment in four-year colleges,” Sarah Cohodes, a professor at Columbia Teachers College, who has studied charter schools. “However, in most cases it is difficult to determine if the enrollment impacts persist through college and to degree attainment.”

“The new KIPP study is very much in line with this pattern, and unfortunately the only way to know for certain is to wait for enough students to get old enough that it is possible to track them to and through potential college graduation,” she said.