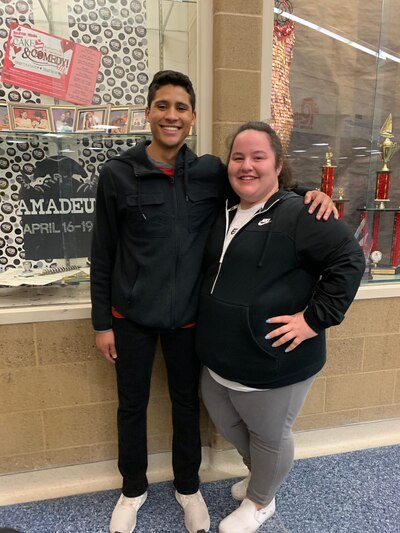

Stuck at home in suburban Omaha, Nebraska, 18-year-old Merlin Padilla has had a lot of time to stare at his college paperwork.

He’s been accepted to seven schools so far, but he still needs financial aid information to help him decide where to go. But that’s tricky right now, since he doesn’t have a printer at home and still needs to mail in some documents. The restaurant where he worked, Cheddar’s Scratch Kitchen, has cut his shift and reduced his pay, so he knows he’ll have even less money of his own to contribute.

And while he’s determined to start college in the fall, he’s not thrilled about the possibility that college campuses may not have reopened by then, either.

“I’m kind of worried that the beginning of the year might be on a Zoom call,” he said.

There are already many barriers that prevent would-be first-generation college students like Padilla from getting to college after they’ve been accepted. And research has shown that low-income students who intend to go to college are more likely than their wealthier peers to drop out of the pipeline over the summer.

But in this moment of great uncertainty — with changes to everything from high school graduation requirements to how colleges are welcoming incoming students — organizations that work with these students say they’re worried that more students than usual will fall off track, and are retooling their work to try to help.

For Padilla, crucial extra support is coming from a coach employed by College Possible, a nonprofit that works with more than 700 high school students in the Omaha area, nearly all of whom are from low-income families and would be the first in their family to attend college. Their one-on-one conversations — and an entire class focused on the college-going process — are now taking place on Zoom.

“These are the working families that are going to be losing their jobs,” said Guadalupe Torres, who oversees College Possible’s work in Washington state. “I do anticipate that we will see a greater number of students not showing up in the fall.”

The months of March, April, and May are critical for helping students navigate the college admissions and enrollment process. It’s when students sit down with counselors and coaches to review scholarship packages and financial aid documents and make checklists to ensure college forms are completed on time.

Already, there are signs that the pandemic is changing students’ college plans. A national survey conducted in mid-March of nearly 500 graduating seniors, most of whom attend a public high school, found that about one in six had changed their plans to attend a four-year college due to the coronavirus. Most of those students said they would go part-time or take a year off, though a smaller number said they planned to attend a community college or work full-time.

Just under two-thirds of students expressed concern that they’d have to change their first-choice college, often because they worried they no longer could afford it. (The survey respondents had an average household income of $88,000 a year, which is higher than what many students from low-income families rely on.)

Organizations that normally help students with college at school have shifted to helping students with those choices online. And like teachers, they’re also relying on calling and texting because some students lack a stable internet connection at home or are sharing devices with their family members.

OneGoal, which works inside high schools in six locations across the country, is moving as much of its curriculum as possible to Google Classroom. iMentor, which pairs high schoolers with mentors over several years, is turning its summer program that prepares students for life on a college campus into a virtual experience. And Torres, of College Possible, said her college coaches, who had experience working remotely, have been training her organization’s high school coaches to connect with disengaged students over the phone.

But one of the biggest concerns these advocates have is that programs that help first-generation students develop a sense of belonging — such as summer bridge programs and college orientations — may not happen in person.

As a result, some organizations are trying to rapidly deploy new programs aimed at making sure graduating seniors who want to attend college actually get there in the fall.

In central Texas, for example, the nonprofit E3 Alliance is working with several partners to launch an online platform that would pair a “volunteer army” with 2,000 graduating seniors from Austin and two other nearby school districts.

“When this pandemic hit we were very, very concerned … that we’re going to see a huge drop in students who are prepared for and successfully transition into college,” said Susan Dawson, E3’s president and executive director, who is trying to put together $700,000 for the effort. “We knew the need was already recognized. It’s an emergency now.”

Ben Castleman, an associate professor at the University of Virginia, has extensively studied what prevents students from matriculating at college. He says more intensive, in-person college advising is often what makes the difference for low-income students.

“That would be my strongest advice: Use Zoom, use other interactive technologies to provide students the closest approximation to in-person, personalized advising that we can to help them through this really challenging time,” Castleman said.

That could mean paying high school counselors to stay in their roles over the summer. Colleges can help too, Castleman said, by taking extra steps to link faculty, alumni, and prospective or incoming students. That could be through virtual tours of dorms and other campus spaces, or showing students what it would be like to take a college class online in the event campuses are still closed.

For now, many college-access programs are helping students stay on track virtually.

Shelby Acton, an 18-year-old high school senior in southeastern Kentucky, recently joined an online meeting with about 15 students and her counselor, Pamela Cate, whose work is part of Partners for Education, a program housed at Berea College that supports high school students across Appalachia.

Acton, who’s planning to attend Eastern Kentucky University in the fall, said she told her counselor over video chat about wanting to cry because she felt so overwhelmed, and how she worried she was annoying her high school teachers because she was emailing too many questions.

Cate told her not to feel bad or to hold back questions, and to make sure she keeps doing her work — even if the result is just a “pass” instead of a grade — so her transcript stays in good shape.

“Being in that group chat made me realize I’m not the only one struggling,” Acton said. “If I didn’t have Ms. Cate, I would probably be losing my marbles right now. She’s just keeping my head level and keeping my stress down.”

But for Padilla, and other students too, video chat sometimes falls short.

“In a Zoom, I kind of spaced out some moments,” Padilla said. “I felt like I wasn’t there in a way. I was receiving the information, but I don’t know, my attention span was very short compared to in person.”

Students and their families are also under increased financial pressure, though it’s unclear how that will affect college-going among this class of graduating high schoolers.

Dreama Gentry, who oversees the 225 college and career advisers who work with Partners for Education in Kentucky, says students in her region are questioning if it makes sense to pay college tuition in the fall.

“As we see an economic crisis, I’m really worried that we’re going to see more young people that need to be in the home to keep the home from falling deeper into poverty,” Gentry said. More students may stay home to care for siblings so their parents can continue working, she said, or take a short-term minimum wage job — her local grocery stores are hiring, she noted — to help make ends meet.

All this is happening at a time when organizations that help students get to college are facing their own financial difficulties. OneGoal, iMentor, and College Possible all said they had canceled fundraisers that had been scheduled for this school year. On top of that, several are raising additional funds for emergency grants to students who need food, laptops, and help paying for transportation.

They’re also worried that next school year there could be a reduction in foundation and private giving, and that school district budgets will be slashed. Several said they’d applied for a small business loan through a $350 billion fund established by the CARES Act — though they’re not sure they’ll receive them, given the high demand. (Congress is already weighing whether to expand the loan program.)

For now, they’re just trying to weather the storm, like their students.

“Our students are survivors, they are persistent, they do know resourcefulness,” said Torres, of College Possible. “And that’s what we’ve got to show, too.”