It seemed unimaginable until it happened — a near complete shutdown of school buildings across the nation.

As coronavirus began spreading in the U.S. in March, tens of millions of students saw their education come to an abrupt halt, as administrators raced to build distance learning programs from scratch.

School as we knew it was redefined in the months that followed. Gone were the teachers lecturing in front of dry-erase boards, students sitting criss-cross applesauce on rugs, children marching to art class or laboring over standardized tests.

What replaced our notion of school varied district by district, teacher by teacher, even family by family. Inequities surfaced quickly. For some American families, the disruption was a major headache, but manageable. But for many others, school closures made a tenuous situation impossible. Due to the economic turmoil, parents needed to leave the house to work. Sometimes students needed to work, too. Children’s disabilities or behavioral issues made remote learning difficult. And experts are only beginning to understand the learning loss that occurred in a single spring.

Chalkbeat asked students and parents who faced a range of challenges during remote learning to reflect on their experiences now that this tumultuous school year has finally reached its end. Their stories show the lengths parents and students went to keep learning, to stay on top of their coursework, to create something, anything that could stand in the place of school. And for some, that effort wasn’t enough, and their educational goals were put on hold.

Completing remote learning — from another country

Ambar Tejada, 21, the Bronx

Three years ago, when Ambar Tejada moved from the Dominican Republic to New York City, she felt immediately intimidated in the hallways of ELLIS Prep Academy, a high school in the Bronx that serves older immigrant students who are new to the U.S.

Everyone around her was speaking English. She didn’t know how to make friends. It was her teachers, she said, who “understand everything” and helped her feel at home.

Those relationships became more crucial than ever this March, when New York City decided to close its school buildings. Tejada, now 21, was looking forward to graduating this year and enrolling in college. But shortly after the pandemic hit, her aunt and some other relatives in the Dominican Republic decided it would be safer for her to fly home as New York City rapidly became the nation’s epicenter for the virus.

Even in another country, Tejada adapted easily to some of the logistics of remote learning. She was able to complete work using a school-issued laptop, and her internet connection was fine at first. There’s also no time difference between the Dominican Republic and New York City.

One big thing, however, had changed. As the news spread of so many coronavirus-related deaths, Tejada lost her drive. “Right now I’m not motivated to do anything, [but] I have to finish,” Tejada said during an interview in May. “I want to graduate because I want to feel my [aunt] proud of me.”

She also missed everything about being in school. “I wish I would be in the school with my teachers,” she said. “I wish I have a graduation. I wish I have a prom. I wish a lot of things.”

By far her biggest responsibility was finishing final capstone projects. One is about civil rights. Another, in science, is about chemical reactions related to chocolate milk. These projects have felt overwhelming to Tejada — “that I can’t do it,” she said.

This is where Tejada’s teachers and her counselor, Jackie Peña, have been vital, Tejada said. They’ve called or texted her daily, often through WhatsApp. Tejada gets messages or calls from teachers who ask her if she needs help, check to see where her assignments are, or just wonder if she wants to talk.

“To be in a different country where the lifestyle is completely different from New York, and to be in a different lifestyle during the pandemic, it’s easy for anybody to lose motivation,” Peña said recently. “But the fact that [Tejada] is still finishing all her requirements, finishing her capstones, getting all her perseverance out, shows a lot of resilience on her part. She wants to prove to her family that she wants to succeed.”

During a Zoom interview with Chalkbeat, Peña turned to Tejada and said, “It’s easy for me as a counselor to work with a student like you, Ambar, because you want it.”

Still, when ELLIS Prep’s virtual graduation takes place Friday morning, Ambar won’t be signing in. After her initial conversation with Chalkbeat, Tejada began experiencing health issues and had trouble with her internet connection.

“She really tried and she wanted to, but she didn’t finish pulling through,” Peña said this week.

Tejada recently returned to New York City and will enroll in summer school with the goal of graduating in August, Peña said.

Tejada still has her sights on college, but she’s worried she’s lost her grasp on English after being out of a bilingual environment for months, Peña said. Tejada wants more time to practice the language, possibly through an English immersion course at a local community college.

Even before Tejada returned to her Bronx apartment, she said she was nervous about what life would be like — could she hug her family and friends? What is daily life going to look like?

“Life is not going to be the same,” she said.

— Reema Amin

When you are both a student and an essential worker

Desmond Bryson, 16, Canton, Michigan

Online classes aren’t the only thing on 16-year-old Desmond Bryson’s plate. The junior at Detroit’s Communication and Media Arts High School, like thousands of teens across Michigan, also has a job.

Bryson doesn’t mind his job as a crew member at a McDonald’s — it has kept him busy during the pandemic, and he gets the personal interactions he misses from classes.

“I enjoy [online classes] but it’s not as enjoyable as actually physically being in the school with my friends and connected with teachers,” he said.

Plus, Bryson needs the extra cash for his future. Many Michigan families are encountering more financial obstacles due to the pandemic, with Michigan’s unemployment rate rising to 24% in April from 4.35% in March, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While Bryson’s pay has remained the same as it was pre-pandemic — $10.60 an hour — he now only works six hours a week. Sometimes, he’ll work extra hours if his manager needs help. Before the coronavirus hit, he worked around 24 hours a week.

Headlines of Detroit’s rising COVID-19 death tolls alarmed Bryson’s mom, Lavelda, at first. “I’m constantly worried,” she said, adding, “However, I’m not as worried because he says he’s taking the necessary precautions to stay safe.”

But Bryson said he feels comfortable at his workplace. In addition to wearing masks and gloves, all employees are required to have their temperatures taken and wash their hands every 30 minutes.

When Bryson returns home from work, he follows his own safety routine. He’ll immediately dispose of his work gloves, throw his uniform in the washer, and take a shower.

Bryson has started mapping out his ambitions for after high school. He wants to study business at a university out of state, using that degree to help promote his clothing line and one day open his own store. Working right now, even during a pandemic, is pivotal to realizing those aspirations.

“You never know what happens, and you might need extra money,” he said. “I would like to get a scholarship, but if that doesn’t end up being the case, I’ll use that money towards my college fund.”

— Eleanore Catolico

Putting college dreams on hold

Eric Bellamy, 20, Newark, N.J.

Even before the pandemic, Eric Bellamy knew it was never going to be easy to make it through college.

One of nine siblings, he had worked throughout high school to help pay the bills, putting in six-hour shifts at a seafood restaurant after class. Still he managed to graduate from his Newark high school last year and enroll in college — a first step towards a degree that nearly two-thirds of his classmates didn’t take.

But like so many students from marginalized communities, he quickly found that persisting in college can be even more difficult than making it there in the first place. For 20-year-old Bellamy, the problem was money. He had trouble paying for his books and affording the fees at New Jersey City University, a public institution in Jersey City. To cut costs, he lived with his family in Newark and commuted to campus. Then, just a few weeks into the semester, he got a call from his mother: The family had been kicked out of their home.

“I walked out of class,” he said. “I didn’t even want to finish school anymore.”

Bellamy moved in with a cousin and her three children last fall and withdrew from the university. But he didn’t want to abandon his dream of becoming the first in his family to earn a college degree, which he hoped would lead to a career as a social worker. So he soon enrolled at Essex County College, a two-year institution in Newark.

Despite all the forces arrayed against him as a Black man from a low-income family, Bellamy was still clawing his way toward a degree. Then the pandemic struck.

“I was already struggling before it happened,” he said. “Now I’m struggling more.”

Systemic racism has left Black Americans especially vulnerable to the coronavirus; during the pandemic, they have died from the virus and lost their jobs at higher rates than white people. And even before the pandemic, Black students were already far less likely to finish college than white students due to disparities in college preparation, access to selective colleges, and wealth.

As a full-time student in temporary housing, Bellamy had no safety net to cushion the blow of the pandemic. After classes moved online in March, he couldn’t afford to buy a laptop nor did his college provide him one, Bellamy said. The campus computer lab and his local library went dark. And he couldn’t borrow the devices that his younger siblings’ schools had loaned them because the district monitored their use, he said. Meanwhile, he applied for a job at an Amazon distribution center but never heard back.

With no way to attend class remotely, Bellamy had to put his college dreams on hold. If he can save up some money, he might try again when — and if — things go back to normal.

“Even though I want to finish college, the pandemic messed me up,” he said. “I just want to wait until everything is like it was.”

— Patrick Wall

‘The longer this has gone on, the more upsetting it’s been’

The Glick family, Staten Island, New York

Staten Island dad David Glick has tried to make the most of remote learning for his three school-aged children, two of whom have significant disabilities. But most of the time, it just feels like “triage.”

His 10-year-old daughter, Emmaline, has Rett syndrome — a rare disorder that affects her cognitive function and ability to speak and walk. When school buildings shut down in March, the family discontinued the one-on-one nurse who helped guide Emmaline through the day, worrying that the nurse might increase Emmaline’s chances of contracting the coronavirus, a bigger risk since her medical condition leaves her more vulnerable.

But without the constant supervision, Emmaline, who suffers from seizures, fell down multiple times, giving her a black eye and bruises across the side of her face. “We do have a one-on-one nurse now. There was no other option to keep her safe while we’re trying to help our other kids do online learning,” Glick said.

At home, Emmaline spends her days watching videos and practicing her communication skills using a device that tracks her eye movements. But even as Emmaline’s nurse gets her out of the house regularly, much of school revolves around structure and opportunities to socialize — “and that’s almost impossible to do online,” Glick said.

Meanwhile, Glick’s four-year-old son Levi, who has autism, has been struggling with severe anxiety. Before schools closed, he had been making progress with making eye contact and with expressing his wants by paging through a series of pictures of things like cookies or even concepts like “happy” or “sad.” (Levi and Emmaline attend Eden II, a state-approved private school whose cost is funded by the government.)

Now, that progress has slowed. “We’re lucky if we can get an hour of instruction done,” Glick said.But even as Levi’s teachers have made efforts to reach out, including a music therapist who holds virtual sing-alongs, Levi has started shutting down. “The other day he pulled a weighted blanket over his head and sat there for two hours and he didn’t want to be touched or disturbed,” Glick said. “The longer this has gone on, the more upsetting it’s been to him.”

Glick and his wife are also trying to stay on top of their nine-year-old daughter Annabeth. Recently, she submitted an assignment by simply writing “hi.” The family is also supplementing her work from P.S. 65, which takes about two hours a day, with lessons from a company called Outschool, a cost of about $20 per day.

Right now, Glick is concerned about the fall. The family doesn’t plan to send any of their children to school to protect Emmaline from the virus, but they are worried that could leave their other two children further behind, especially if online teaching hasn’t improved much.

“Will good online instruction be in place for those who choose not to go back to a physical building?” Glick wonders. “It needs to be a lot better than what it is now.”

— Alex Zimmerman

A school year marked with anxiety

Savannah Storms, 16, Fountain, Colorado

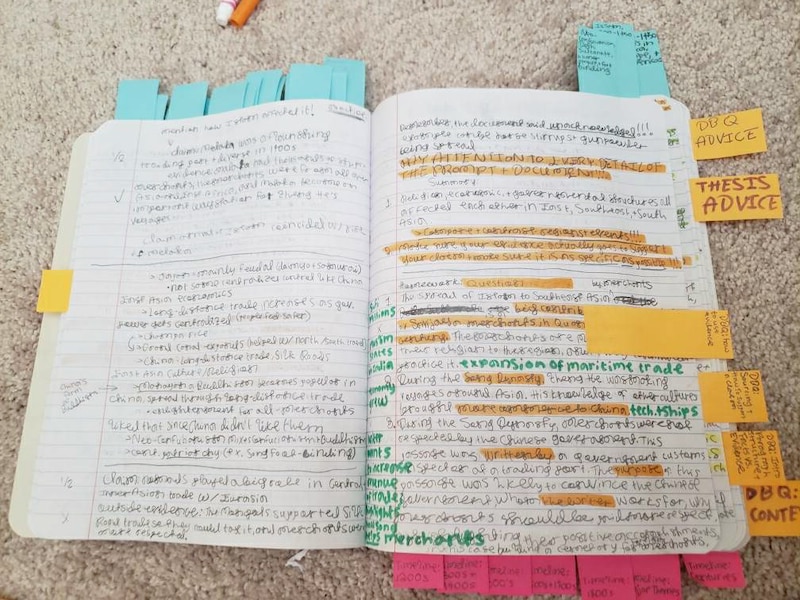

When schools first closed, Savannah Storms’ biggest source of anxiety was having to study for her very first Advanced Placement test on her own and submit it online. What if the server crashed when she went to click submit?

That proved to be just one of many unsettling moments for Storms, a sophomore at Fountain-Fort Carson High School who said remote learning was made more challenging by her generalized anxiety and ADHD.

“I was terrified of coronavirus. I was really scared. I was like, ‘Why am I living in a time like this?’ because my anxiety is really bad,” said Storms. “I’m not good without a structure. I had to make my own and it was really overwhelming. It took about a month for me to find a strategy for studying.”

During the first few weeks of isolation, when she still had hope school would be back in session by April 30, Storms tried to study for her AP test alone. But she said her brain was so occupied with the virus she mostly just stared at old material.

Storms said one thing that helped reduce her anxiety was taking ownership of information she was consuming. At first, she was watching NBC News videos on YouTube and reading articles on her SmartNews app. Some of those news articles really scared her because they were talking about young people dying.

“I was scared during Ebola and I didn’t live anywhere near it,” said Storms. “And this was a real thing that was everywhere. I got really terrified.”

The killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer similarly upset Storms at a time when she already felt fragile. “I felt like I had a responsibility to fix it. I, as a Gen Z, have this responsibility to help Black Lives Matter,” said Storms. “That put a lot of pressure on me and I felt a lot of anxiety about it.”

Storms finished the school year with all A’s. And now she’s waiting to see what fall has in store. She, like so many others, wants to go back to school.

— Claire Bryan