These stories were originally published by Newsroom by the Bay, a digital media program for high school students. Students around the world were asked: How have you been reacting, navigating, and adapting to the remote learning experience? They wrote about their experiences this past school year after buildings closed due to the coronavirus. In some places, school was back in session by late spring; elsewhere, campus reopenings were delayed further. Hear from more students at their website, coded and created by student editors.

Learning from home in difficult times

By Magdalena Andjieva, 16, Ilsfeld, Germany

In normal times I would attend the Steinbeis Gemeinschaftschule (Steinbeis Community School) in my hometown, Ilsfeld. But since the school closed on March 16, I’ve been working on my own.

Recently we returned to our school again, but as the situation hasn’t cleared up yet, we don’t attend classes as usual. This means that we go to school only for a few hours then work from home again.

The homeschooling situation during isolation was a bit difficult for me since I had no one to help me out beside my friends who texted with me, and that was difficult in itself. We didn’t have video chats with our teachers very often. We were given homework with only a few instructions, and sometimes not even that.

My parents weren’t able to help me out since we are foreigners and don’t know the language very well. My first language is Macedonian; I came to Germany with my family when I was 13 years old. When we first came here, it was really hard for me since I couldn’t speak the language very well. I was able to understand more. Staying in a foreign country and having to learn the language isn’t as easy as it might seem. You do have a lot of contact with native speakers, but my friends were also foreigners, so we often found ourselves struggling when trying to explain something.

Those were difficult times but I’m sure whoever is going through the same understands me. There are thousands of people around the world struggling. It might seem like you’re alone, but trust me, you aren’t.

In order to do my homework, often I had to ask my classmates for help, or try and do the work on my own using the books we had been given at the beginning of the year.

I can’t say that my academic life has gotten better during isolation. I’ve had many troubles with my homework and mental health. I feel like not being able to go out of the house for more than a week — let alone months — messes with your head. Other than doing homework, all I’ve done was help around the house a bit or stay on my phone, watching videos and catching up with friends. It wasn’t a very interesting time.

I hope the situation gets better and we begin again with school as we normally would.

‘What I had hoped for, no?’

By Diego Garcia, 17, Toulouse, France

It was a Thursday in mid-March, and rumors of President Macron’s potentially grandiose speech were swarming in all the lycées [high schools] of France.

There was a climate of apprehension, as though we all knew what the outcome of his speech would be but were too embarrassed to vocalize our joy. Macron announced that evening the closure of all educational facilities. And I couldn’t help but feel a guilty smirk spread across my face. At the time, a slow descent into perennial laziness felt welcome.

“This is what you had hoped for, no?” Mum asked.

My smile vanished, ceding its place to an expression of simple acceptance. It wasn’t long until social media was saturated with jubilant posts and stories celebrating the switch to online learning. Initially, it felt novel. The first day was a breeze. I’d never been so relaxed.

I spent the whole first week of online school euphorically flying through my classes. Sitting all day on my chair and jumping from videoconference to videoconference seemed so exciting and easy. For most classes, I slumped back into my chair while listening to introductory lectures and being dismissed to complete assignments.

But the novelty soon started to wear off. I began to feel the complacency. The buzzing of the videoconference notification became deeply annoying, and I couldn’t help but let out a sigh of frustration every time it peeked out on the side of my screen. I directed my frustrations towards the teacher favorite Microsoft OneNote — a digital portfolio for students to organize their work. At first, I thought it was useful and innovative, but then it became an exercise in online school tyranny. With my reduced, fish-like attention span, I began neglecting to upload my work. I was keeping up with lessons but forgetting to turn in assignments.

Schools in France are slowly returning to in-person learning. At the time I’m writing this, primary students have returned and will be followed by the secondary students. There is a rotation for students to go to school on set days — “Group C” goes on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. But I’m still at home. It’s not clear if the students in my year will be able to go to in-person classes or not.

Now I feel a cycle of mismatched emotions. When I wake up, there is a sense of anger. At lunch, a feeling of freedom because I can stand up and walk around. During the evening, a sense of relief emerges. But as one day blends into the next, relief is quickly replaced by annoyance again.

It’s not what I had hoped for.

Three boxes waiting by the door

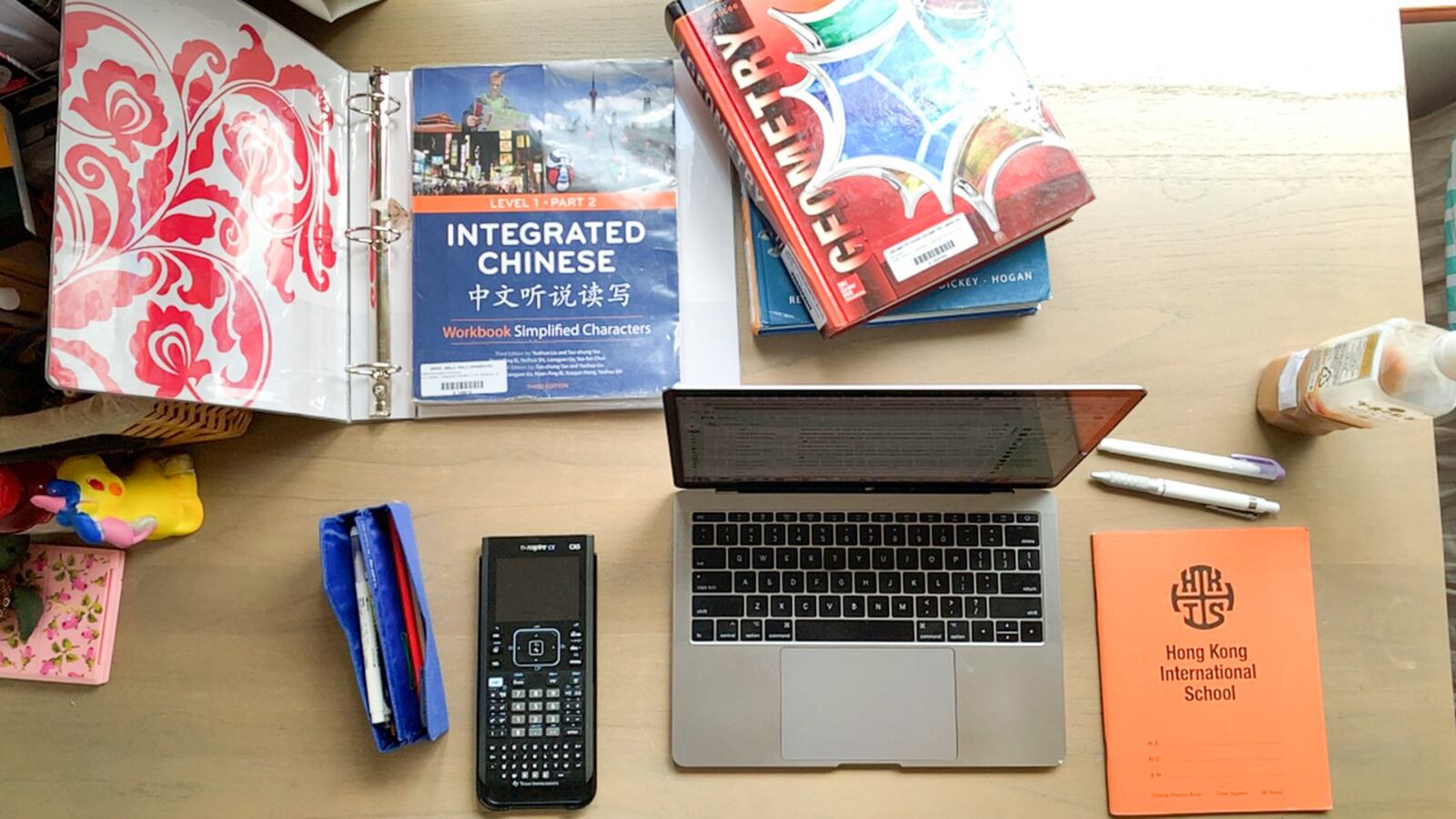

By Erika Hornmark, 14, Hong Kong

My family keeps three boxes of masks by the doorway, above the dusty shoe cabinet that hasn’t been opened in a while. The boxes can be seen in the corners of my Zoom video meetings.

At the beginning of my school year, wearing masks in groups was banned in my hometown of Hong Kong because of their symbolic roles in the Hong Kong protests. Now if I’m seen without one, it’s grounds for upset stares and finger-pointing.

I was on vacation in Bangkok, Thailand, with my family when reports of rising fatalities from the coronavirus began appearing in the news. Social media buzzed with rumors that schools in Hong Kong would close after the Chinese New Year that began Jan. 25.

Two weeks later, I was in front of a computer, watching my biology teacher flip through slides. I lay sideways on my bed, camera and microphone off — just like everyone else in my class. My mother doesn’t believe in studying inside the bedroom, so I don’t have a desk.

Some of my classes have been impressively organized, with teachers updating lesson plans and hosting well-attended video meetings. Others have been lackluster, rarely assigning material with rushed five-minute Zoom conferences only twice a week. I often feel like I’m teaching myself.

Many of the tests I’ve taken have been on simple Google Forms and Schoology, and most worksheets have been taken directly from online sources. It would be easy to cheat, easy to avoid the minimal adult supervision. Many teachers have resorted to cutting out large chunks of the curriculum.

I sometimes feel exhausted by long interactions with my family. But as long as I wear a mask, carry hand sanitizer and stay in groups of four or fewer, I’m allowed to see my local friends in person. I’ve been surprised — as a person who is naturally private and reserved — by my frustration at not being able to see people every day.

I look forward to sitting in a class of 20 once again. I look forward to hearing my classmates debate controversial topics in my humanities class, and sitting with my friends in front of the taco stand in the cafeteria.

I look forward to when there aren’t three boxes of masks by the doorway.

Sharing a phone, learning without friends

By Ifeoluwa Martins, 14, Lagos, Nigeria

I am 14 years old. May 1, the day I’m writing this, is my birthday.

In normal times I attend Gaskiya Junior Secondary School in Ajegunle, a neighborhood in Lagos, Nigeria. My school closed in late March, around the time we were going on spring break. My school had no distance learning plan, and we have been given no resources.

I study now with Miss Shola Shoroyewun, a community leader who helps five of us with our lessons. We are cousins and siblings living in the same compound.

None of us has a computer or Wi-Fi. So we share Miss Shola’s phone. We are also using a new website called Safleaders. It includes the junior and senior secondary curriculum that we have in school — English language arts, civic education, mathematics, and agricultural science.

Using the website is cool and easy. You can download what you need to read very fast. We just pass the phone from student to student, or one of us will read to the others.

The last assignment we got from Miss Shola was to do a personal narrative. We looked up what was required and then we talked and Miss Shola broke everything down. If I have more questions, I know she can answer them.

I miss my friends, I miss the cooperation between students, I miss the group projects and lessons. I would rather be back in my traditional school. But there are so many students in my classroom that I can’t count them — it feels like 100.

Even though we are in lockdown, I feel happy. My academic life is better now than before. I can focus more on my studies and I have time for my own projects.

My learning space is my bed and when I am not doing schoolwork. I like to read there. The book I am reading now is by Ben Carson, the U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, who has says he has family roots in Kenya.

The title is “Think Big: Unleashing Your Potential for Excellence.”

‘Dark times, but I see light’

By Eugene Halim, 17, Jakarta, Indonesia

I could feel the news was coming. But I didn’t want to believe it.

With only a week until opening night, we had been practicing day and night for our school play, hoping for a perfect performance.

Then after a particularly grueling 10-hour Saturday practice, our director told us that the play was canceled. Our cast of 100 people immediately broke down in tears, cries echoing in the dark hall as the musicians put down their instruments. I sat behind my drum kit, my skin stinging with the reality of what was happening.

Since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed, the situation in Indonesia has worsened. The number of new cases has increased and unemployment has soared, with no end in sight. Public buildings are closed, concerts canceled, public transport shut down, and our school switched to online instruction.

It took me awhile to adjust to the new system, but I’ve slowly realized that my learning experience has actually improved. Classes have become more efficient; my teachers have spent more time discussing material, instead of taking attendance, and are much easier to contact after school hours. I can re-watch lectures if I don’t understand something. I’ve had enough sleep and a quiet work environment.

I’ve saved a lot of time by not commuting through three or four hours of traffic every day. With more free time, I practice drumming, cook, and play video games. I’ve also had extra time to work on my history research paper.

Still, there are things that I miss. I took the everyday for granted — participating in club activities, spending time with friends, and being able to have face-to-face conversations. I no longer get to see my brother this summer because he’s studying in the United States.

But I keep looking for blessings in disguise. Spending rainy Saturday nights with my parents has brought us closer. With our typically busy routines, I didn’t realize I was missing deeper, personal conversations about our lives, opinions and the future. We’ve recently spent time together building a hydroponic farm, going on family walks, and bingeing our favorite Netflix shows over midnight snacks.

The times feel turbulent, dark and unstable, but I see light in the opportunity to reflect on the little things that really matter.