I am a public school social studies teacher in Northern California. My job is sometimes terrifying in scope: teach the state standards, which cover everything from early man to the present day, to 87 students who range in age from 11 to 14.

I’ve struggled with how to present the entire history of humankind in a way that is both interesting and digestible. Over the years I have become better at it, focusing in sixth grade on how societies are formed and in seventh grade on the rise and fall of empires. In eighth grade, I am confronted with U.S. history, which in the age of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, I feel enormous pressure to teach with both accuracy and sensitivity.

When I was in school, we were taught that Columbus was a hero who discovered America and that the Pilgrims and the “Indians” shared friendly meals and culture. I was taught that the Civil War had to do with states’ rights, and that slavery, while bad, was a brief moment that was now behind us. I remember hearing about the suffering of Irish and Italian immigrants but never about the Chinese Exclusion Act or Japanese internment camps.

Those are obvious distortions, omissions, and discredited interpretations. But other key pieces of history are more complicated to determine how to teach, especially to middle schoolers. Do we get into Lincoln’s web of motivations for freeing enslaved people? FDR’s failure to stop the slaughter of Europe’s Jews alongside his efforts to rebuild the U.S. from the Great Depression?

I have learned over the past five years that there is no easy way to teach our history. It’s messy. It’s complicated. Heroes are often also flawed, and I don’t want my students to think I have all the answers. Instead, I want to teach them that the way we learn about our history is all about the questions we ask.

Teaching history can also be painful. Showing my eighth graders the tortured face of Emmett Till is the hardest day of my school year. I wish I could share his picture and say the bravery of his mother Mamie Till Mobley, who made the decision to share the mutilated face of her son on the cover of Ebony magazine, led to an end to racist violence against young people of color. But that would be a lie.

I am white, as are almost all of my students, and that makes things more complicated in other ways. Here in the hills of Northern California, in a community where many deeds still have restrictive covenants on them, it can feel like we are too far removed from certain parts of American history. Several years ago, when it came to my attention that some of my students were casually using the N-word and homophobic language outside of class, my concern only deepened. Black culture was a subject of fascination, but Black people were being denied their humanity.

I decided my normal teaching tactics weren’t enough. In 2019, my students and I raised money to fly from California to Georgia and Alabama. Our school is small and forever chasing dollars just to cover the basics. But parents, students, administrators, and ultimately our community came together and made it possible.

I could see on my students’ faces that they truly understood what it meant to deny someone’s humanity.

In Alabama, we visited the Rosa Parks Museum, the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the 16th Street Baptist Church. We discussed heroes both Black and white. We studied the ways in which people sacrifice for change. We stood where people died because they believed in a better world; we stood where children had been killed in a terrorist attack.

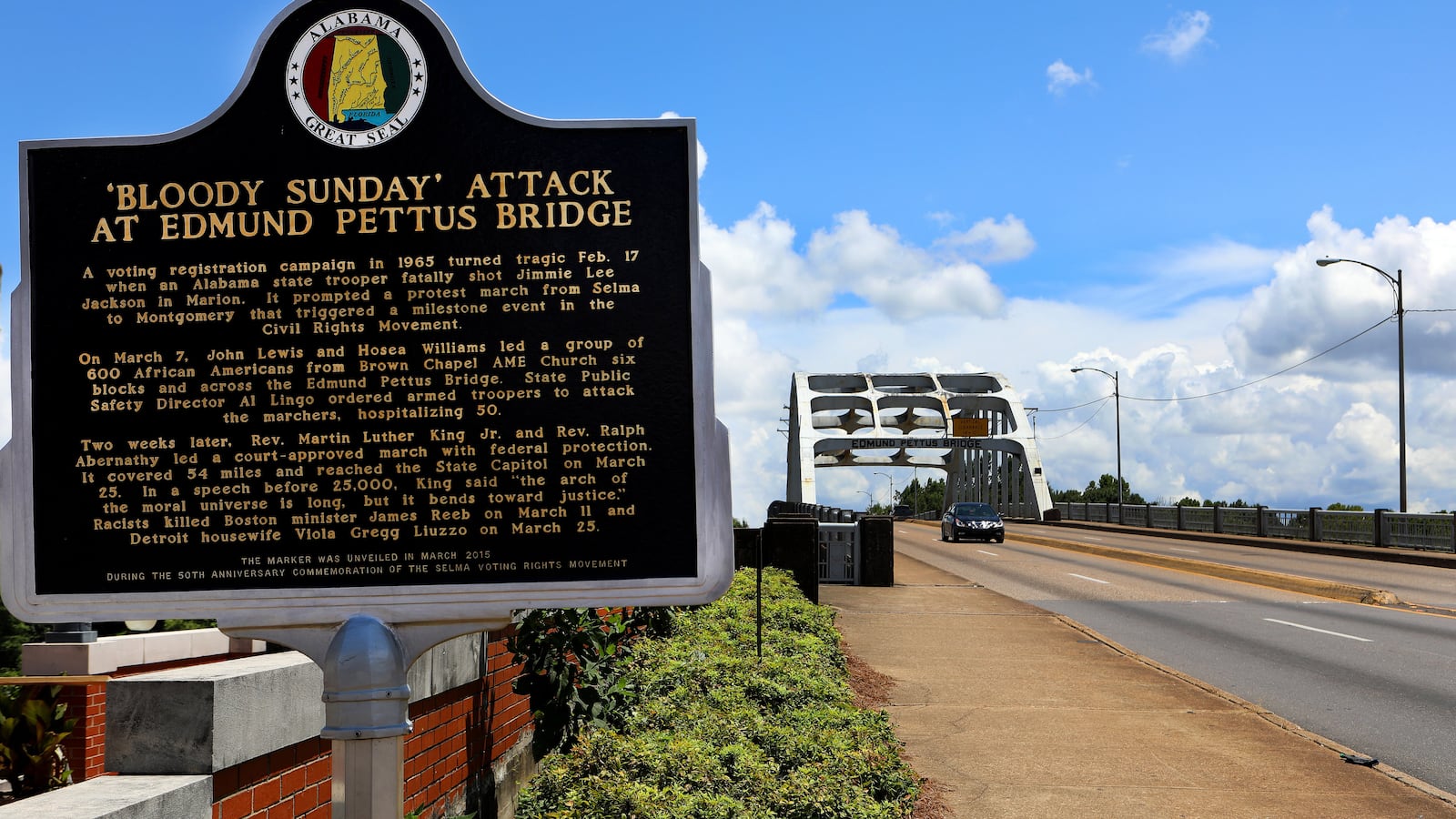

My class also had pen pals from a school in Alabama, and we met in person the day we were scheduled to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where, in 1965, peaceful civil rights marchers were viciously attacked. Many of the local kids had never been to the bridge either, so it became a shared experience, its gravity new to all of them.

I had foolishly forgotten name tags the morning that we were all due to meet, only to find that because of social media the students all recognized each other and greeted each other joyfully. Watching the students make those connections, and learn from one another, was beautiful and sometimes funny. My students learned that their counterparts liked college football as much as they loved the Golden State Warriors. And after seeing their pen pals interact with me and their teachers using “ma’am” and “sir,” my students asked me roughly one million questions about it.

The most powerful learning experiences came at museums that brought history alive. At the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery, there are holograms of enslaved people in cages awaiting sale. One was calling repeatedly for her children from whom she had been separated. Several students had to walk back outside to catch their breath, and I could see on my students’ faces that they truly understood what it meant to deny someone’s humanity.

On the last day of our trip, we were in Atlanta at the National Human and Civil Rights Museum. There was a lunch counter and stools set up, and if you sat at a stool and placed your hands in a particular spot, and put on headphones, it would simulate the experience of sitting at a lunch counter while people shoved, yelled at, and harassed you. There were docents at each end of the counter and they advised the kids that if at any point it got to be too much they could remove their headphones. Many students wept silently as they sat there, the stools jostling. I watched as one student who sat for quite some time stood up and started to walk past the docent. The woman just a few years older than her gently touched her arm and asked if she wanted a hug. My student looked up and said, “Yes, ma’am.”

When we came back to school, I felt like I was teaching a completely different class of students. We held events so that the students could educate the community about what they had seen. I heard them speak with confidence and conviction about some of the most difficult parts of our history. I heard them describe the things they had seen and heard, and could see that in the re-telling they weren’t just educating the community but also connecting what they had learned to the world they lived in today.

The trip left me with this message for my community: Trust your schools and your teachers. Trust your kids to hear hard things and have hard conversations. We don’t have to agree on everything. But let us agree that we want our children to understand our real history to equip them for a better future.

Katherine Sanford is a parent and teacher in Northern California.