For the past four years, I served as superintendent of Oxnard School District, located 30 miles up the California coast from Malibu. But unlike Malibu, most of our school district’s 14,000 students come from low-income, Spanish-speaking families.

Yet, not all of our Latino families consider Spanish their first or second language. Nearly 500 families reported speaking Mixteco, an Indigenous language of Southern Mexico, which has scores of variants. For a long time, though, Mixteco wasn’t represented in any of our literacy materials, often making it hard for families to read together.

Despite the prevalence of the Mixteco language, our students sometimes felt ashamed to report their Mixteco heritage or identify with their unique language and culture, Argelia Alvarado Zarate, one of our school district’s Mixteco translators and community support liaisons, told the Oxnard school board last spring.

“I was told not to say that I spoke Mixteco because it was something that we couldn’t share with other people who weren’t from our community,” said Alvarado Zarate. Growing up, she said, she yearned to have something in her native language to show that speaking Mixteco was “nothing to be ashamed of.”

Looking to change this, Alvarado Zarate and others on our family and community engagement team decided to support our Mixteco families and bring their culture to life through storytelling. The idea to translate digital books into Mixteco first sprouted a few years ago at a family reading night at one of our schools. There, Norma Zarate Cruz, another one of our school district’s Mixteco translators and community support liaisons, translated a book into Mixteco for some of the families in attendance.

Because Mixteco isn’t a written language, we had to make some decisions to ensure the greatest accessibility.

“They’re always told to go home, read to your child,” Alvarado Zarate told the school board. “But the same answer that they always give the teachers is, ‘I don’t know how to read or write.’”

Mixteco is a spoken — not a written — language.

Recognizing the literacy barriers that our Mixteco-speaking families faced, Alvarado Zarate and Zarate Cruz approached our school board with an idea to help these students and their families read together. They got approval to translate some of our digital books available on myON, the educational software company Renaissance’s digital reading platform. The app gives students access to digital books that match their desired language and interests.

We then partnered with Renaissance and worked with them to translate digital books into written (transliterated) and spoken Mixteco. Now, Mixteco-speaking families throughout Oxnard have 25 books they can enjoy together. For the first time, our families can listen to stories in their native language and read stories that appreciate and preserve their rich culture.

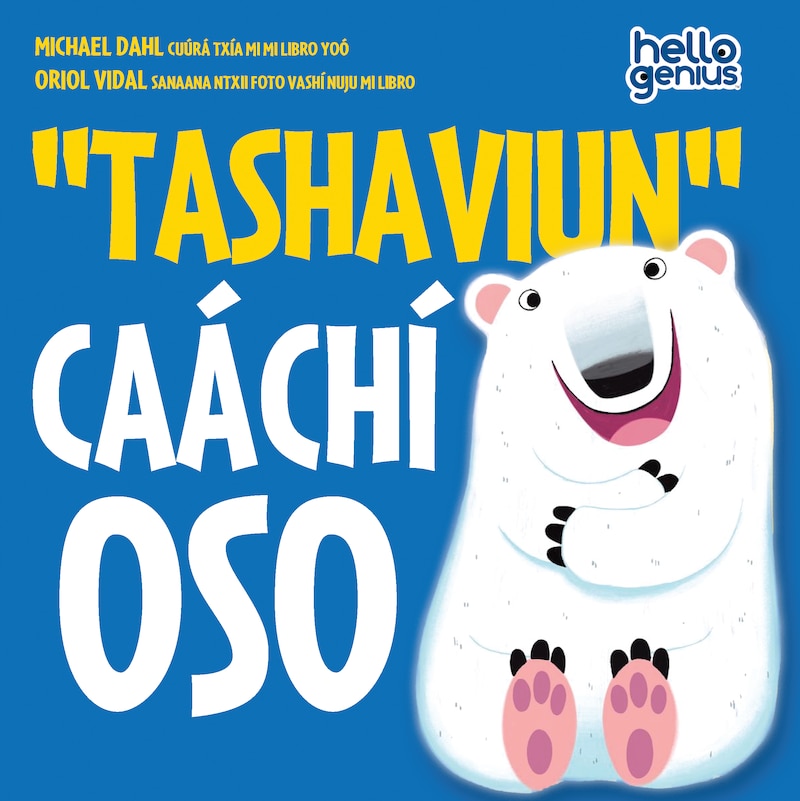

Alvarado Zarate and Zarate Cruz carefully chose the book titles, looking for topics that would most engage Mixteco-speaking students in the younger grades. They chose themes focused on overcoming bullying, maintaining cultural pride, and spreading kindness, including “Tasha Viun Caáchl Oso,” translated from “Bear Says ‘Thank You.’”

Because Mixteco isn’t a written language, we had to make some decisions to ensure the greatest accessibility. In each of the digital books, the text follows Spanish phonics, and the recording was spoken in the San Martin Peras variant of Mixteco. The audiobooks include two familiar voices: Zarate Cruz’s and Alvarado Zarate’s.

I know how important it is to foster inclusivity, diversity, and an appreciation for the languages and cultures that make our communities thrive. I also know what it’s like to feel excluded as a non-native English speaker. I’m originally from Venezuela, where I worked in special education before I began teaching in the Spanish Bilingual Special Education setting at San Francisco Unified School District several years ago. From there, I came to Oxnard.

At Oxnard School District, we designed a student profile to message the key traits we wanted our students to develop before they graduated. Two of these traits connect to equity, diversity, and inclusion, and one focuses on developing students to be global thinkers. We want our students to interact and solve problems with people across a diverse spectrum of races, ethnicities, and gender identities. The other focus speaks to students’ development into digital learners who carry with them a sense of cultural identity and pride, so as they learn to solve the problems of the future, they never forget where they’ve come from.

Our Mixteco translation project supports these goals — encouraging families to embrace their native language. To truly reflect diversity, equity, and inclusion, we know that content must go deeper than honoring heroes and holidays. We cannot pretend that we understand and reflect the different cultural backgrounds of our student population if we don’t elevate others who can speak to those experiences.

With this effort, Mixteco has “been given light,” as Alberto Mendoza, a district parent support liaison, put it. “It’s been given that space to say yes, you and your language are part of us.”

Dr. Karling Aguilera-Fort served as Superintendent of Oxnard School District from 2019–2023. Earlier this year, Dr. Aguilera-Fort accepted a role as the Site Associate Superintendent of Educational Services at San Francisco Unified School District.