Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Every August, Jamar McKneely feels the pain of what was lost. This year has been harder than most.

It’s been 20 years since Hurricane Katrina submerged his city — and upended life and learning in New Orleans, where McKneely now leads the InspireNOLA charter school network.

Before Hurricane Katrina, McKneely taught math and entrepreneurship and coached football at Edna Karr High School in the city’s Algiers neighborhood. He was one of about 7,000 school district employees fired in the months after Hurricane Katrina. The teacher workforce comprised mostly Black women in the majority Black city, and many educators received their pink slips while they were still evacuated.

Water had breached the New Orleans’ levees on Aug. 29, 2005, flooding about 80% of the city. Nearly 1,400 people died due to the storm, the subsequent deluge, and the flawed federal response to the disaster.

Katrina pummeled New Orleans at the very beginning of the 2005-06 school year — leaving most of the city’s public school buildings damaged, some of them beyond repair. A few city schools reopened within months, but it would take years for others to welcome back students. By that point, the school system looked very different.

State lawmakers repurposed the Recovery School District, formed before the storm to turn around low-performing schools statewide, and allowed it to take over more than 100 New Orleans public schools, including ones that had previously met the state’s performance standards. The Recovery School District incentivized charter operators to reopen campuses, and only a few high-performing schools remained under district control.

With these newly minted charter schools came an influx of teachers recruited by organizations like Teach For America and TeachNOLA. Many of them were white and from out of town, with limited training or classroom experience.

Today, the New Orleans school system serves a much smaller student population. Enrollment now stands at about 42,000, down from about 65,000 before Hurricane Katrina. In 2019, after the last remaining district high school was handed over to a charter operator, New Orleans became an all-charter district. Just last year, though, the local school board opened the Leah Chase School, its first traditional public school in nearly two decades.

Today, New Orleans’ high school graduation rates and state test scores are way up, and a higher percentage of city students are college-bound.

What this transformation means remains highly contested. Charter advocates tout New Orleans as a poster child for education reform. Others lament the number of veteran educators who lost their jobs and seniority, and argue that the charter system promotes competition rather than collaboration between schools.

For his part, McKneely said he’s proud of New Orleans’ transformed school system, but loss will always be part of the story.

“As much as we’ve been working to gain an educational system that is promising, that has unique growth, I revert back to the pain,” McKneely said. “I still revert back to being terminated. I still remember how many homes were lost, how many individuals lost their lives, how many educators are no longer in this space.”

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina, Chalkbeat spoke with five New Orleans educators about surviving the storm, teaching in Katrina’s wake, and how they understand the seismic changes to the city’s school system. Their comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The football players at Edna Karr High School were already in their uniforms when Jamar McKneely told them that Jamboree — the tournament marking the start of the season — was being postponed. It was Aug. 28, 2005, and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin had just issued a citywide mandatory evacuation order. McKneeley gave the disappointed players a pep talk before driving 80 miles to his parents’ home in Baton Rouge.

We told the students to be safe, be careful, listen to their parents, and hopefully, we’ll return within the next two to three days, after the storm has passed.

When I saw how flooded the city was, when I saw how many people were displaced on roofs, the realization hit me that we would not be returning to New Orleans as normal. Even though that was happening, what was on my mind was: When could we return? How would we help rebuild? What was happening with my students?

I started receiving phone calls from my students saying they were displaced, they were on buses, they were going to Texas, they were going to multiple different people and places. That was the most important thing, providing assurance to them as we try to get through this. But for myself, I didn’t know how I would pick up life. And then, before I even started looking for another opportunity to work, I received a termination letter. I didn’t know how I would survive.

McKneely spent the rest of the school year teaching in the Baton Rouge district, where some of his former students had enrolled. In the spring, Edna Karr’s principal invited him back. Before the storm, Edna Karr was a district-run selective admissions school; after the storm, it became an open-enrollment charter school. He accepted the position, commuting from Baton Rouge for months before securing a FEMA trailer in New Orleans.

I wanted to come back to show them a sense of normalcy. I didn’t care what it looked like. I didn’t care what it sounded like. I just wanted to be back with my students that I had been educating before, those who returned gradually, or those who were there for Day 1. At first, it was, like, we survived. You made it, I made it, we’re back. We tried to do a lot around the social-emotional space to understand together what we had experienced.

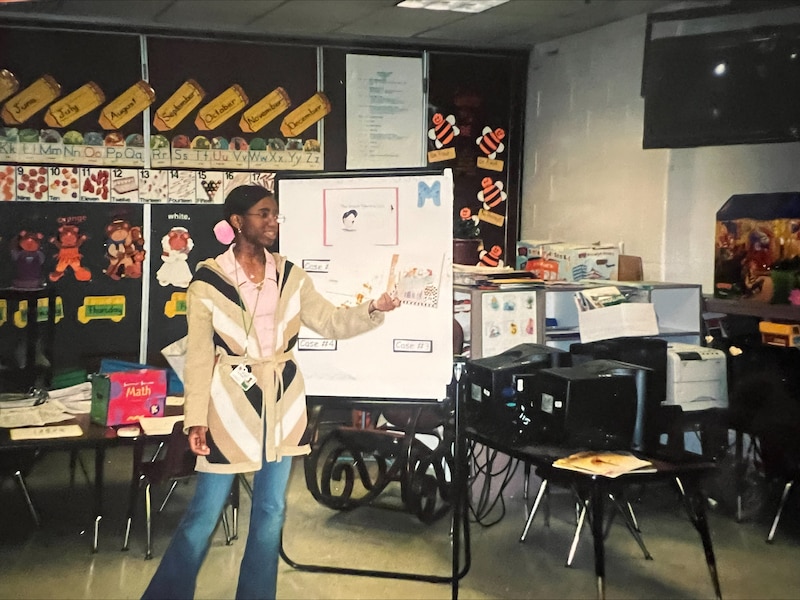

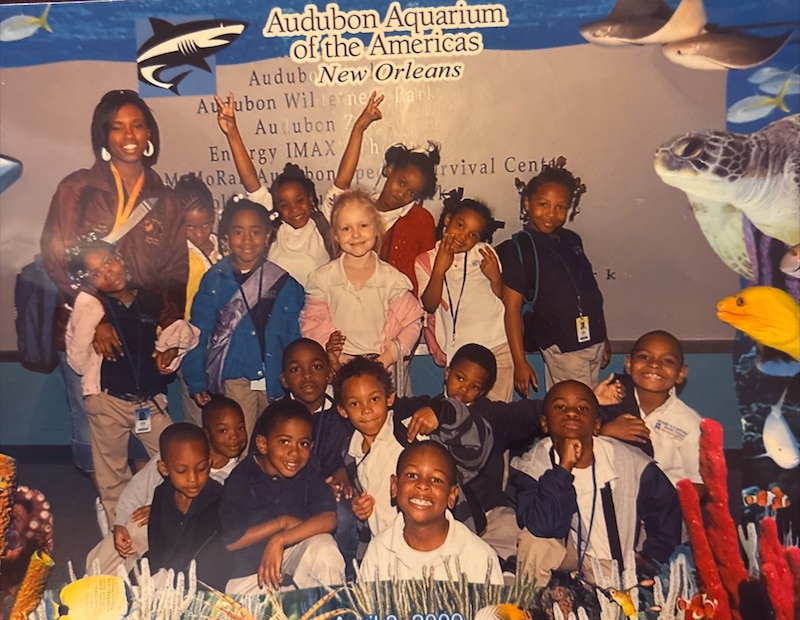

The week leading up to Hurricane Katrina, Alicia Harris was working off the clock to set up classrooms and computer labs at Fisk-Howard Elementary School, where she was a paraprofessional. She had been so focused on the start of the school year that she hadn’t known a storm was coming until her brother asked her if she was evacuating. She decided to ride out Katrina at the Hilton where her brother worked, and she ended up at the epicenter of the botched federal response.

I was inside the Hilton hotel, but you could say I was on the street because you had no lights, no water, no nothing. They ran out of food. People dead on the street and you see them floating in water. I was stuck in New Orleans until Sept. 7. That’s when I made it to Virginia, and when I was able to take my first real bath and find something real to eat.

Before the storm, Harris was enrolled in a district-sponsored program to train paraprofessionals to become teachers. After Katrina, the program was eliminated. Harris is now in her 26th year as a paraprofessional in New Orleans.

A few years ago, Harris began pursuing a degree in elementary education. An aspiring school principal, she was also accepted into a union-run teacher leadership program. She still works full-time with fourth, fifth, and sixth graders with disabilities at Leah Chase, the city’s only district-run school.

Katrina set me back 20 years, for real. … It set me back a lot because I lost — well, everybody lost — everything. I was in a situation as a para educator, struggling in school, and when Katrina hit, it just made everything worse.

I didn’t get any assistance from FEMA — that was the first thing that really hurt me. You hear people talking about, I got this from FEMA, I got that from FEMA. Hard as I worked for the city, child, I didn’t get nothing. So I have been struggling from that moment that Katrina hit, up until now. Even now, with me being a full-time student, it’s a struggle. I’m carrying 19 [credit] hours, just trying to finish so I can make the money doing what I love, and that’s teaching.

What I really want to do is become a principal because I have all these years of experience in school. I know how to run it now. Let me show you how to run it!

I will be graduating, probably, this time next year, and I’m so excited. I can’t wait. Someone said to me, “Miss Harris, you’re going to be a great principal.” I said, “I know I will.” I said, “Things take time.” I know I can do it.

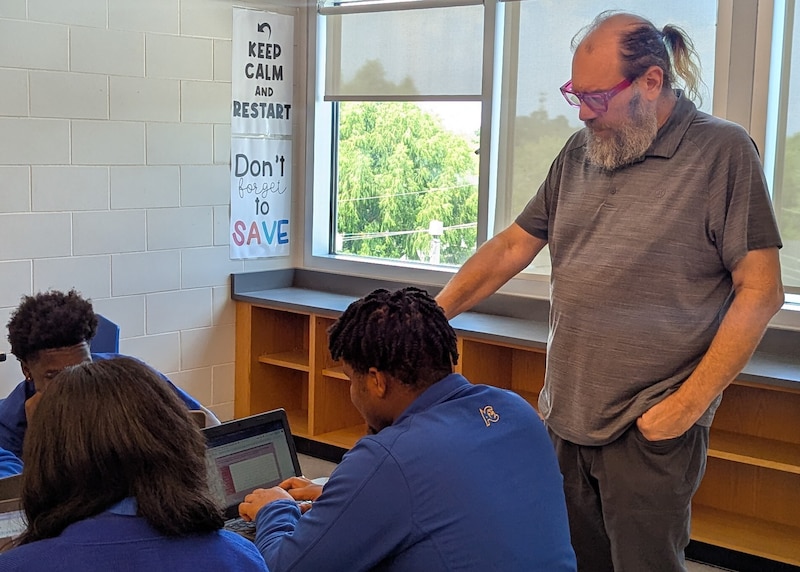

Dave Cash wanted to help rebuild his adopted hometown post-Katrina, so the web developer decided to become a teacher. Today, he teaches career and technical education at L.B. Landry High School and serves as president of the United Teachers of New Orleans union. His first teaching job, though, was at George Washington Carver High School, which reopened in August 2007. Classrooms were set up in trailers on the city’s sprawling Ninth Ward campus. Humvees were a frequent sight in the area, as the Louisiana National Guard continued to patrol the city.

A lot of students, when they evacuated to Houston or Atlanta or other places, were bullied or called refugees, so they wanted to come back to New Orleans. There was a significant number of young people who came back without their parents.

So that was an interesting thing as a teacher: If a kid is acting up in class and I call home, sometimes their girlfriend answers, because that’s who they live with. And their girlfriend is obviously not going to have a conversation with them about their behavior in class. Everything was not normal.

In the first 12 years I taught, I was at two different schools, each for six years, and I had 11 different principals. That’s an instant way to explain how tumultuous it was and how difficult it was as a new teacher to grow when your leadership is constantly changing over.

Cash credits veteran New Orleans educators, many of them Black women who had been fired following Hurricane Katrina, for helping him through those chaotic first few years in the classroom. After school, he would often hang out at the teachers union office, where many of the veteran educators congregated and volunteered.

There was this tension, because there was this really strong narrative that the reason why New Orleans needed charter schools was because the teachers were the problem and had been ruinous for the city beforehand. I think there were people that were teaching that maybe didn’t respect the veteran Black educators, but I wanted to learn from them. … They would just talk to me about my day and help me find the courage and the energy to go on.

For as long as she could remember, Brittany Smith wanted to be a teacher, like her father. She attended a teaching academy program at New Orleans’ Benjamin Franklin High School. She was a sophomore education student at the University of New Orleans when Katrina hit. Her family evacuated to Texas, and then moved temporarily to Georgia while their house was rebuilt. Returning to New Orleans a year later, Smith completed her degree and became an elementary school teacher. She is now the principal at the Edward Hynes Charter School — UNO.

In New Orleans, whenever you ask people what school they went to, they’ll always say their high school. The pride was always there, but now to see it thriving after such devastation in New Orleans, I think it brings about a stronger pride in our resilience, in our ability to say: Even though we felt like [the city] was completely wiped out after the storm, here, my school still stands. They still have kids in the building, and they’re thriving.

I feel like everyone came back with the purpose of providing a place of structure and high expectations for learning with input for everyone. So I feel like the charter school system [served us] well.

Smith teared up reflecting on what she wants her students, all of them born after the storm, to know about Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath.

In education, it was a loss of connection, a loss of stability for some kids, a loss of continuity. I would want them to know how strong the people of New Orleans were. To go through that, and still have the desire to come back and rebuild takes a lot of strength. And to let them know that they are coming out of people who are very strong, which makes them, therefore, a very strong student. And letting them know that there was this huge challenge that students who were once their age overcame. To know that whatever you may face, you can overcome that — I think that’s the biggest thing I want my kids to walk away with.

On her Teach For America application, Stevona Elem-Rogers said she would “teach anywhere.” TFA placed the recent college graduate in post-Katrina New Orleans. The Alabama native taught high school English before getting a job at the Teach For America organization. She now serves as chief of community programs and partnerships at BE NOLA, a nonprofit supporting Black-led efforts to improve education in New Orleans. The organization’s Black Is Brilliant Summit in October will feature sessions reflecting on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

I came in 2007, and I had no context that the Black teachers had been fired. All the teachers had been fired, but specifically, that they were majority Black, and majority Black women. The choice to join this context wasn’t given to teachers on either end — to me, who is coming from college, and to Black veteran educators. Many of them wanted their jobs back and were told, “No, we can’t give you your job back,” and then you find out that somebody has your job who never taught, and you taught for 15 years.

That first year in the classroom, Elem-Rogers said she leaned heavily on the Black veteran teachers at what was then O. Perry Walker High School. They helped her pass her math licensing exam, which she initially struggled with, and encouraged her to enroll in a traditional teacher training program, through which she eventually earned a master’s degree.

They’re trying to help kids who went through one of the most traumatic natural and unnatural disasters of our time, and they are also helping me, a first-year teacher, have context for where I am and also how to teach. They had the added labor of helping me be a good teacher, on top of trying to rebuild their homes, on top of trying to make sure that the kids who experienced the greatest trauma are taken care of.

They didn’t have a choice in that either, and they don’t get credit, the ones who did get their jobs back, for helping mold a whole generation of teachers.

Gabrielle Birkner is Chalkbeat’s features editor and fellowship director. Email her at gbirkner@chalkbeat.org.