School boards in Chicago and Illinois have cut short time to hear public comment — just as public concern and questions about education have grown.

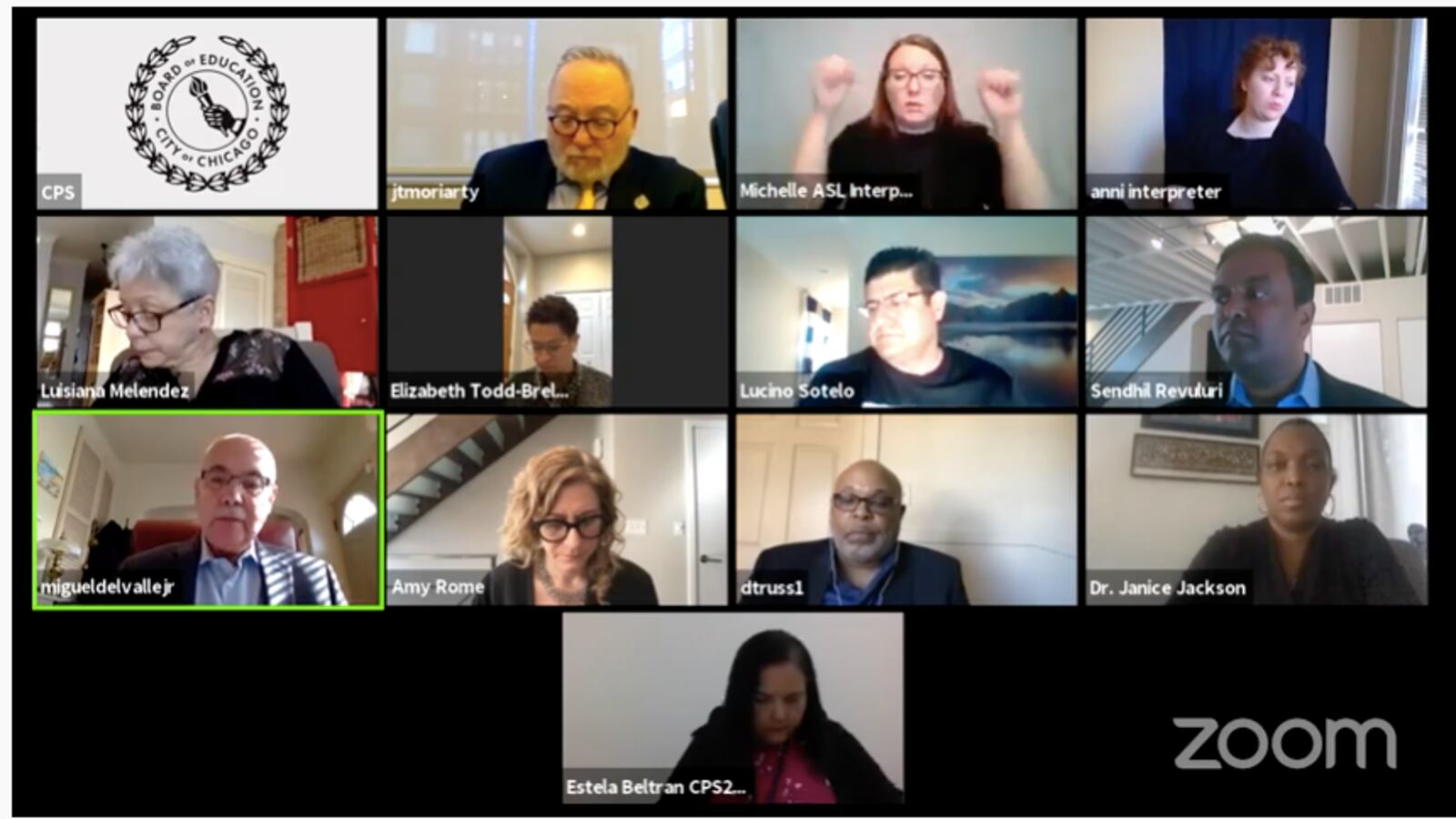

The boards, both appointed, have done this by cancelling meetings and limiting the number of speakers or the time allotted to them at meetings held online.

The Illinois State Board of Education, the body charged with drafting the new rules on school days and remote learning, cancelled its monthly board meeting in April. Its next meeting is May 20.

The Chicago board, which usually kicked off its monthly meetings with hours of public testimony from up to 60 parents, students, educators, and community groups, now permits only 15 speakers for a total of 30 minutes.

In a statement, Chicago Public Schools said it set the call-in limit to only have 15 speakers because the call-in system used by the district required public commentors to spend hours waiting on the phone before being patched in, a timeline that was unsustainable for 60 speakers. It would also significantly lengthen the meeting, a representative said.

“The Board of Education has always prioritized and will continue to prioritize public participation under the emergency circumstances, which necessitate a different approach to public participation,” a statement from the district said.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s March 16 executive order closing bars and businesses also suspended the portion of the Open Meetings Act requiring in-person attendance for public bodies. That gave them the flexibility to make their meetings virtual and broadcast any changes to public comment rules.

According to a statement posted in the Chicago board agenda, the order also allowed public boards to make sure that meetings were “expeditious“ in order to “maximize time spent directly addressing the needs of the students and families during the public health emergency.”

But some critics worry about the restrictions limiting public comment. After the March meeting of the Chicago board of education, some community groups said they were not able to get on the list to speak, while more than half of the list was from one school community, Lincoln Park High School.

Those concerns have cropped up around the country as school boards and other governing bodies operate under looser rules made possible by hastily crafted executive orders and board motions.

In Memphis, Tennessee, the school board conducted a secret, closed meeting by videoconference. In Newark, New Jersey, the board granted the superintendent sweeping authority.

So-called “sunshine laws” vary by state, but they generally require public agencies to publicize board meetings in advance and make them accessible to the public.

The Illinois State Board of Education, which videocast its March meeting and had some board members meeting in the same room, postponed its April meeting. It gave as its reason “to protect public health and safety“ and because agenda items did not require immediate action. The board accepts public comment in writing, but has not yet confirmed a public participation schedule for its next meeting.

The Chicago school board rules on public meetings say participants may submit written comments, or sign up for a 15-minute office hours meeting with a board member. It also says the board president can amend the board meeting guidelines.

Jianan Shi, whose group Raise Your Hand usually has at least one speaker at a regular public comment session, said he appreciates that Chicago Public Schools has follow the guidelines of the Attorney General’s office regarding responses to the Freedom of Information Act, but he wants to know why the board has limited public participation to only 15 speakers per meeting.

“If there is no issue with having 60 slots, we should have 60 slots,” he said.