The first week of school highlights yet another facet of the challenge Chicago faces in supporting newly arrived migrants: enrolling their children in school. For the past two days, I saw it up close while helping two migrant families enroll their daughters at a neighborhood high school in Brighton Park.

These families, recent arrivals from Venezuela, are among more than 1,200 migrants currently sleeping in police stations; about 6,500 more are staying in local shelters.

Since mid-July, Chicago Public Schools has been beefing up its efforts to enroll migrant students. The district opened a welcome center at Clemente Community Academy in West Town. School officials say they have enrolled about 1,000 new English learners over the summer and expect 1,000 more to enroll in the coming weeks. However, there’s no way to tell how many of them are recently arrived migrants. In a last-minute push, the district said teams from the Office of Language and Cultural Education are visiting police stations to help migrant families staying there to enroll.

And together with mutual aid groups supporting migrants at police stations, the Chicago Teachers Union held a Zoom training for volunteers helping families enroll and signed up migrant students as part of a back-to-school party at union headquarters.

Yet some families are still struggling to get their children in school. As the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times reported, volunteers and young migrants staying in South Side neighborhoods with few Latino students say schools have turned them away because they lack staff qualified to teach English learners.

But even enrolling in schools with the staffing to support new arrivals can be daunting, especially in high school, where the red tape is extra-thick. As a volunteer with the mutual aid network for the 9th District police station in Bridgeport and a longtime education writer, this is what I saw. I’m sharing it here with the families’ permission. Their names have been changed because their asylum cases are pending.

Monday, Aug. 21, 2023

7:45 a.m., Kelly High School, 4136 S. California Ave.

While hundreds of Kelly students wait to enter school on the first day of the new year, I’m meeting aspiring freshmen Sofia and Marianna and their respective mothers as they get out of another volunteer’s car.

Inside, a security guard tells us registration for new students doesn’t start until 9 a.m. We can wait or come back later. The four of them haven’t had breakfast, so we head out.

8 a.m., Tio Luis Tacos, 3856 S. Archer Ave.

Over plates of pancakes for the girls and eggs with nopales, chorizo, and cecina for the grown-ups, we get to know each other a little. We speak in Spanish, though mine is only mediocre. Like many migrants coming to Chicago, Rosa, Sofia’s mom, says her family has been at the Bridgeport police station for three weeks. She and her husband have two children: Sofia and a 1-year-old boy.

Maria, Marianna’s mom, tells me her family has been at the station for just 10 days. In addition to Marianna, she and her husband have two other children: a 10-year-old boy and a 4-year-old girl. Both of them have already been enrolled at Holden, a neighborhood elementary school close to the police station. Her 10-year-old went to Holden on time for Day 1; her little girl has to wait while they make sure the preK has enough room for another student.

They tried to enroll Marianna there, too, but the school staff said she had to move on to high school due to her age: She’ll turn 15 in February.

Marianna has a taste for the salsa roja on the table with the chips, which makes both moms laugh. From volunteering, I know that Venezuelans, unlike Mexicans, don’t usually like their food spicy. Sofia is the more talkative one, convincing Marianna to have pancakes with her. Both girls love the pancakes, which vanish quickly. The sausage, not so much. Sofia takes some of her scrambled eggs in a to-go box.

9:10 a.m., Kelly High School, Door 4

When we get back to Kelly, a few other families are waiting by the registration entrance — Door 4. They have been buzzing, but no one is answering. I press the buzzer just for good measure, then text one of the lead volunteers with the District 9 group, who teaches at Kelly.

It’s starting to get hot outside. Maria holds her manila envelope full of papers up against her right cheek to shield her face from the sun.

After a few minutes, the Kelly teacher opens the door for us. We walk up to the security guard, who is helping with registration. She looks at the papers in Maria’s folder and a smaller stack of papers Rosa brought. Both moms have their daughters’ birth certificates, but neither has any transcripts from previous years. Both girls completed seventh grade in Colombia before making the trek to the U.S., their mothers say, but there are no records.

The security guard says she can’t register them without a transcript evaluation. How do you do a transcript evaluation without transcripts? We’re not sure what to do next, so we step out.

The Kelly teacher meets us outside and texts me a photo of a flyer outlining a two-step process for transcript evaluation. It’s translated into Spanish and Chinese. Step 1: Call the downtown office to make an appointment. Step 2: Bring the following documents downtown for review: a birth certificate and/or passport (if they have one) and any grades or transcripts they have from previous schools they attended outside the U.S.

I call the office to ask if we need an appointment, and the woman on the phone says we can come right away. So, off we go.

On the way, we make a pit stop back at the police station to pick up Sofia’s little brother. Rosa thinks it’s better for her to have him if we’re going to be gone for a while.

Maria’s husband, Juan, is at the station with Marianna’s little sister, who can’t start school today. They want to come, too. Juan especially wants to meet me since we haven’t met before and now I’m driving his wife and older daughter all over town. So we all pile in my ‘97 Camry. Juan sits shotgun; the moms and kids are squished together in the back.

On the way north to the Loop, I ask Marianna’s and Sofia’s parents if registering their children for school in Colombia had been easier. They say yes.

10:25 a.m., Chicago Public Schools Central Office, 42 W. Madison St., Garden Level

We walk through the revolving doors and down the stairs. Two security guards sit behind a Plexiglas barrier. I explain that we called ahead and name the person who is expecting us.

After a short wait, another staffer comes to meet the two families. She interviews them in Spanish and confirms both girls were born in Venezuela. Then she asks, in Spanish, “What school are you accepted to?” The girls and their families all give blank stares because they haven’t memorized the name of their soon-to-be high school yet.

“Kelly,” I answer.

The central office staffer asks, “Is that a neighborhood school?”

“Yes.”

Later that night, I received messages that suggest I might have misheard the question about neighborhood school. It’s possible she asked me, “Is this the neighborhood school?” The messages I received indicated that CPS wants families currently in police stations to register at the neighborhood school nearest the station, and then transfer if the school can’t provide the services they need.

But that’s really hard on people who have been living in constant motion, especially children. Our mutual aid group decided to bring them to Kelly because it is a convenient bus commute from the police station, has bilingual teachers, and English as a second language class. There’s also a teacher there who is also a mutual aid volunteer to help them if they have any problems.

Finally, the staffer comes back with some new papers to add to each family’s stack, allowing them to go ahead and register their daughters as ninth-graders at Kelly.

11:54 a.m. Kelly High School, Door 4

We’re back. This time, Door 4 is propped open. We tell the security guard we went downtown and show her the additional papers. She gives each family a packet of enrollment papers to fill out.

The security guard asks Rosa for her ID. It’s back at the police station. Rosa, Sofia and the little guy pile in the car with me to go get it.

By 1:05 p.m., we’re back at Kelly for the fourth time today. The chances Sofia and Marianna will get any class time on Day 1 have already vanished. Now I’m afraid Sofia’s registration gets pushed another day too.

But the guard gives her a number – 45 – on an index card and tells us to wait in the auditorium. Marianna and her family are already there, among a dozen other families, holding an index card with a number, too. Hers is 40.

1:30 p.m., Kelly High School Auditorium

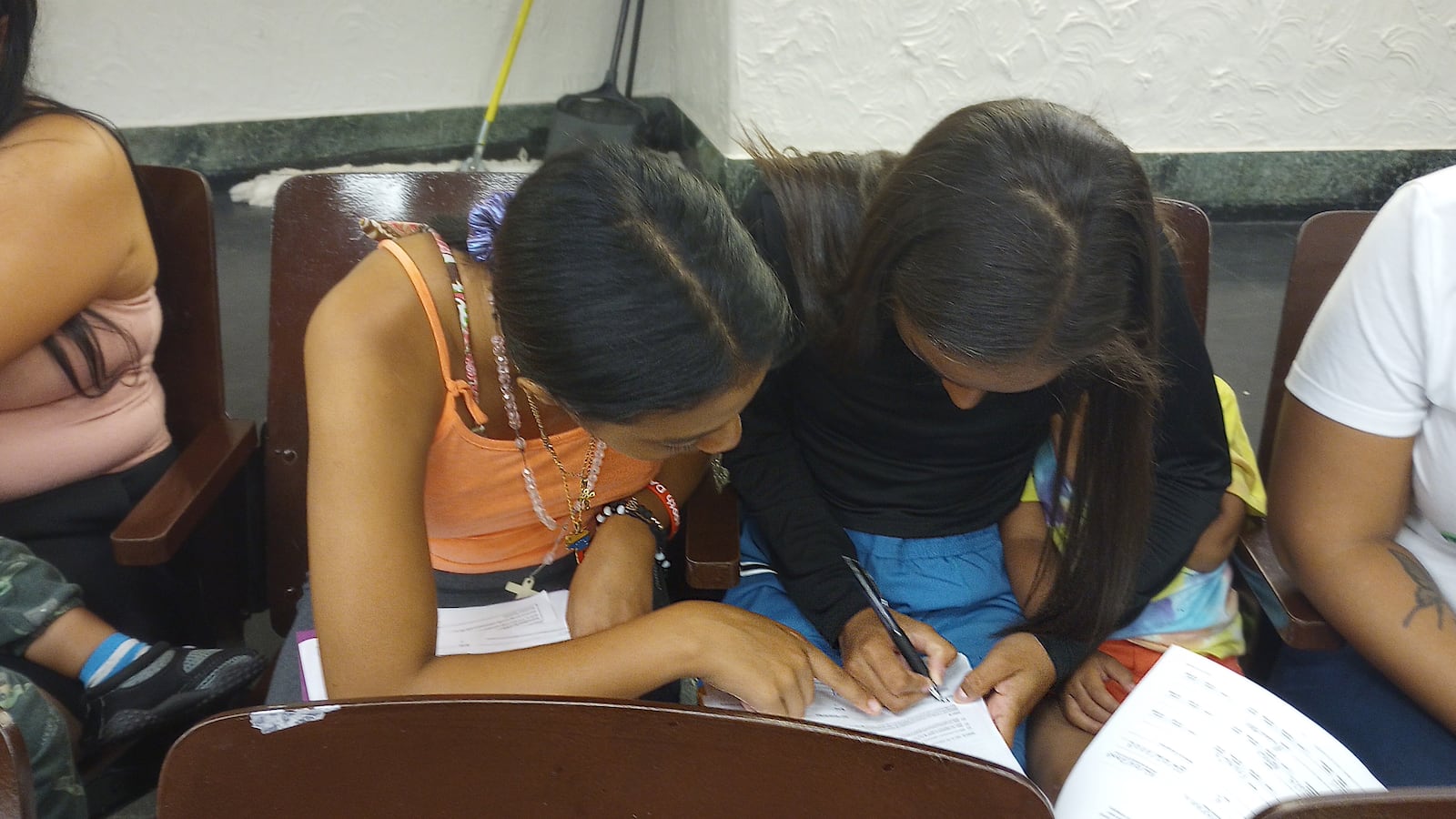

While waiting, Sofia and Marianna fine-tune all the paperwork. Heads bowed, they tick off the to-dos. Media release, done. Consent for school text messages, done. Racial/ethnic survey, done.

A short woman walks in and calls the number 33. A family follows her out of the auditorium. Sofia’s baby brother sleeps in his mom’s lap. Marianna’s little sister miraculously fell asleep while sharing a wooden auditorium seat with her big sis. The older girls are yawning. Eventually, they each put their head on their mother’s shoulder, their long hair hiding their faces as they burrow in for a rest.

There are two counselors down near the stage. I ask them what happens next. They say the girls must get registered in the main office; then, they can receive class schedules. If the girls don’t make it to the main office today, they will have to come back at 9 a.m. tomorrow and keep on waiting.

Suddenly, there are end-of-day announcements coming over the intercom. They’ve missed the first day, and it’s looking like they won’t be able to attend class tomorrow, either.

2:47 p.m. Kelly High School Main Office

Finally, Marianna’s number – 40 – is called. I follow her family to the main office, where they get to wait again, this time in padded office seats.

When Marianna and her parents start talking with the school clerk, she asks for two proofs of address. I interrupt and say, “They are STLS,” which means students in temporary living situations. These students are legally entitled to enroll in school without the usual documents.

Once that’s done, I play with the 4-year-old while Marianna and her parents hand over the paperwork. Eventually, the clerk shares the good news before the bad: Marianna is officially registered. But tomorrow she’ll have to come back at 9 a.m. tomorrow to take an English proficiency test before she gets a class schedule.

We head back to the auditorium. Sofia and her family aren’t there; their number has been called, too. Both girls are registered and can test tomorrow.

We leave Kelly around 3:40 p.m. No one except Sofia has eaten since breakfast; she had her leftover eggs.

Tuesday, August 22

9:10 a.m. Kelly High School, Library

Tuesday morning, Sofia, Marianna, their moms, and the 1-year-old all come with me to Kelly while the girls take the English-language placement test. While we all wait in the library, a teacher brings in a box of donut holes to share with all the families waiting to register or have their children test for English placement. After about half an hour, a teacher comes in to take Sofia and Marianna downstairs for testing.

I leave them my cell number to call when the test is finished. When I return, the girls and their mothers are outside, talking with two young women who appear to be Kelly students. I join the circle between Sofia and Marianna and ask in Spanish, “How did it go?”

“Excellente!” Sofia says with a wide smile. Marianna smiles shyly, and I stretch my arms each way to give them both a quick shoulder hug. Soon after, the conversation wraps up, and we head back to the station.

Wednesday, August 23

8:00 a.m. Kelly High School, Main Office

At the office, the girls get paper printouts of their schedules. The secretary says they can get IDs and bus passes at lunchtime.

When they see they have a class together, they squeeze hands and smile. Then they head to their first-period class: English as a Second Language.

Maureen Kelleher is a volunteer with the District 9 mutual aid group and a longtime education writer. She previously wrote a First Person piece about choosing a new school for her daughter.