When I moved to Crete, Illinois, in 2021, I didn’t expect a five-day curriculum unit to change how I saw my community or myself.

Tapped by the county to work on a new Underground Railroad unit, I came to the project with an educator’s mindset and a heart for justice. What unfolded over the next several months, however, was more than a lesson plan for local students. It was a journey of reconnection, reckoning, and restoration. And it all began with a question: What would it mean for students to see themselves not just as learners of history, but as part of it?

That question anchored our team of educators’ work as we developed a unit exploring the Underground Railroad through the lens of Caroline Quarlls. Quarlls’ journey from slavery to freedom began in St. Louis; she passed through Crete on her way to Canada. Bolstered by a county grant, my colleagues and I designed the middle and high school curriculum with a deep commitment to place-based education and social-emotional learning.

To ensure authenticity and accuracy, we consulted local historical resources and received invaluable insight from the Crete Area Historical Society and Museum. These partnerships helped us understand our community’s role in the broader narrative of the Underground Railroad.

Yet one of the most formative parts of this journey didn’t come from a textbook or archive. It came from listening, deeply and humbly. After completing the initial curriculum, I realized that while the first edition was grounded in good intentions, it had not adequately included the lived expertise of Kimberly Simmons, a direct descendant of Caroline Quarlls.

That realization, which Simmons pointed out after she saw the lessons we devised, stopped me in my tracks. Instead of moving forward with that version of the unit, I reached out and arranged to meet Simmons virtually and later in person. I also had the opportunity to engage with Dr. Larry McClellan, a distinguished historian whose work has focused on the Underground Railroad in Illinois. McClellan and Simmons are co-authors of “To the River,” a vital text that became central to our unit.

Simmons welcomed me into a conversation that became a turning point. I attended a symposium she led at the University of Windsor in Canada, where she illuminated the deep historical connections between the Detroit River, Canadian freedom, and the networks of resistance that carried freedom seekers across borders. Her perspective, and the truths she carries with both authority and grace, reshaped how I understood the narrative we were teaching.

She personally reviewed the revised unit, helping us to correct a significant inaccuracy regarding Quarlls’ motive for escape. It was a reminder that good intentions don’t replace responsible storytelling. Proximity to a story doesn’t equal ownership. It was a lesson in what it means to approach this work with the respect it deserves.

What emerged from these relationships wasn’t just a powerful social studies unit. It became a dynamic way for students to connect with the land they walk every day. Through maps, primary sources, and values-based reflection, students didn’t just learn about the Underground Railroad. They traced its path through their neighborhoods. They explored how places like the Crete Cemetery and Crete Congregational Church connect directly to stories of resistance, courage, and legacy. Some students even brought their families to visit these sites, sparking long-overdue intergenerational conversations.

Be bold enough to ask what history lives in your backyard. Be brave enough to learn what you were never taught.

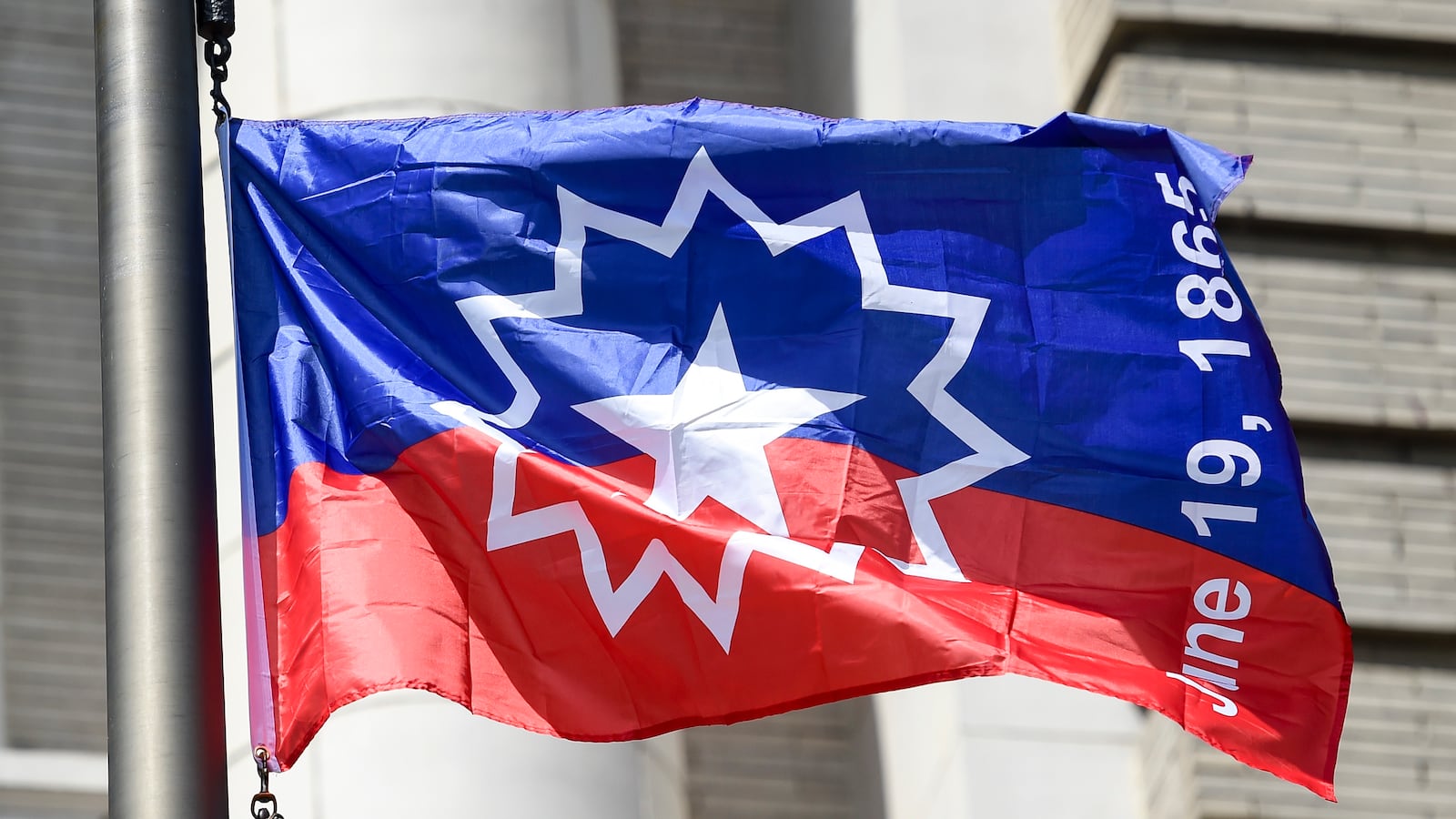

This curriculum didn’t stay in the classroom. It led to the Village of Crete’s first organized Juneteenth celebration in 2023, a small but deeply meaningful event sponsored by family and the Crete Area Historical Society and Museum. That gathering grew into a larger event called Juneteenth at the U, supported by Crete-Monee School District 201-U, local businesses, Monee Township, Prairie State College, and Governors State University. Like the curriculum, the celebration was rooted in truth-telling, joy, and reclamation.

Eventually, this journey led me to co-author, with Dr. Rita Guzmán, “We Celebrate Juneteenth Unidos,” a bilingual children’s book inspired by Juneteenth at the U. Through the voice of a grandmother and her granddaughter, the book invites families to see Juneteenth not as a historical footnote, but as a thread connecting past, present, and future.

Throughout this process, I’ve learned that you don’t need to be a credentialed historian to begin this work. You don’t need to be an expert to care deeply or lead thoughtfully. What you do need is a willingness to listen, to be corrected, to seek out those who know more, and to let your curiosity guide you with humility and care.

We are all part of living history. The more we approach that truth with a curious and open spirit, the more meaningful our learning and our teaching become.

To every educator, parent, neighbor, or community leader reading this: Let this be your invitation. Be bold enough to ask what history lives in your backyard. Be brave enough to learn what you were never taught. And be willing to say, I didn’t know, but I want to.

Because honoring the past doesn’t just shape the future. It shapes us.

Valerie Butrón is an educator, speaker, and co-founder of Tumbao Bilingual Books. She bridges curriculum and community to bring overlooked histories into classrooms through place-based, student-centered storytelling.