Denver Public Schools officials say they are starting their search for curricular materials aligned to the Common Core State Standards in math and English language arts all over again.

It’s been four years since Colorado adopted the Common Core in language arts and math as part of the Colorado Academic Standards. Starting next spring, the state’s standardized test in the subjects will be tied to the new standards.

But DPS has yet to adopt or purchase a new set of curricular resources aligned to the Common Core.

District officials say that the textbooks and other academic resources that are on the market right now aren’t up to snuff, especially for Denver’s large population of English learners.

“It’s a real struggle right now,” said Alyssa Whitehead-Bust, the district’s chief academic and innovation officer. “Finding a curriculum that’s that’s been redesigned for the Common Core is difficult enough—and finding one that’s aligned for English learners is a different challenge.”

The district reviewed the Common Core-aligned textbooks and curriculum on the market last year, Whitehead-Bust said, but decided that none was worth the millions of dollars the district would have to invest.

The district then decided to create a new curriculum in-house. “That was Plan B. And that turned out to be equally challenging,” Whitehead-Bust said. “Now we’re back to the drawing board.”

Whitehead-Bust said there was no clear date by which the district was guaranteed to have new resources. “We’re continuing to move forward with research and investigation,” she said.

In the meantime, DPS teachers are in limbo, adapting resources that were created with the previous state standards in mind to create lessons that are aligned the Common Core.

Redesigned, not realigned

The Common Core standards for English language arts and math have been adopted in 43 states and the District of Columbia (Minnesota adopted only the standards in English language arts). Though the standards have stirred political and educational controversy, Denver officials say they are more rigorous and will encourage better teaching and learning.

But Denver is not alone in having not found new Common Core-aligned curriculum and textbooks, said Carrie Heath Phillips, program director for Common Core State Standards at the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), which helped develop the standards. “Many places didn’t want to rush to buy new materials until there were more quality resources out there.”

She said that’s starting to change: Some states, including Tennessee, Louisiana, and Hawaii, have recommended lists of textbooks that are aligned to the standards.

In Colorado, each district chooses which curriculum and resources it will use. Some districts, including Boulder, have adopted new curricular resources tied to the Common Core.

Whitehead-Bust said that DPS is searching for something that’s not simply old textbooks with a new label. “There are a lot of companies that have remapped their material to the standards. But they haven’t redone their material. We’re looking for materials that are really redesigned, not just realigned.”

In the meantime, she said, teachers haven’t been totally without updates and support. “What we’re trying to do is take the resources that were in place last year, many of which were really strong and solid resources, and deepen the rigor of the content, infuse more informational text, and deepen expectations around text-dependent questions, so we can really guide teachers through.” Elementary English language arts teachers have gotten new guided reading books for their students. A literacy newsletter has suggestions about how to tie lessons to the new standards.

“Great resources in the hands of less-than-well-trained teachers don’t have anywhere close to the same impact as well-trained teachers using resources you’d hoped to replace and upgrade over time,” she said.

But weaving old materials together with new additions aimed at making lessons more rigorous or aligned with the new standards isn’t always easy.

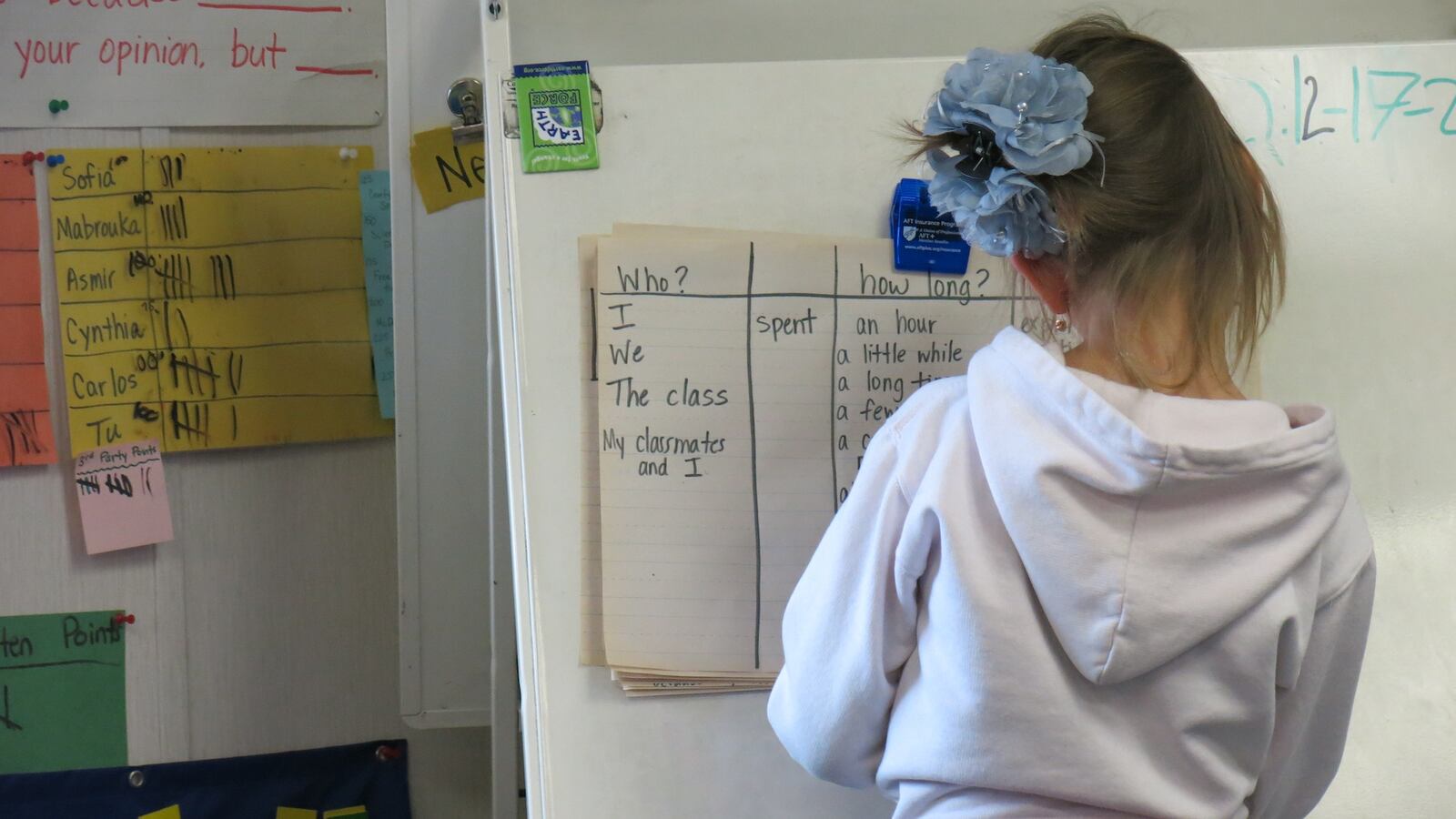

“They do provide us with a lot of resources,” said Margaux Rowley, a second grade teacher at Ellis Elementary, in southeast Denver. “But sometimes you’re getting so much—it’s, ‘do this with the scope and sequence,’ ‘do this with the standards.’ It’s a lot of information.”

Rowley said that making sure the lesson plans and instructional materials she uses in class line up with the standards, and with how other grades in the school are interpreting the standards, is a challenge.

Theresa Winslow, a fifth grade teacher at Ellis, said that math materials are more up-to-date than language arts. “In literacy, we’re still tied to the lesson guides from ten years ago.”

Frustrated board

At a meeting of the district’s board in November focused on academic programs and teacher and leader training initiatives, board member Arturo Jimenez said he was concerned about the delay. “If we don’t have the curricular materials chosen and implemented and ready to go, it’s difficult to see the logic that we’re focusing on teacher leadership development, evaluation and incentives,” he said. He compared it to sending paratroopers into battle without parachutes.

“How do we focus teachers without planning and practice guides, without curriculum that’s focused on the Common Core? It seems like we’re doing it backwards,” he said.

Superintendent Tom Boasberg said while he understood the concern, “we have kids on the ground who desperately need our teachers. Are not going to say we’re not going to coach or develop them?”

Whitehead-Bust described the district’s efforts to “bridge” between old materials and new. “Many districts are in our position,” she said. “It’s frustrating for teachers.” She said there would likely be an update to the timeline for finding resources as the district develops its new strategic plan this winter.

Board president Happy Haynes said she was surprised to hear that materials appropriate for English learners were hard to come by. “I don’t know why it took [publishers] so long to figure out that that’s an extraordinary need—but we need to keep the pressure there in order to get the materials we need.”

Challenges for English learners

States and districts have been developing ways to make sure the standards are accessible to English learners, according to the CCSSO’s Phillips. The state of New Jersey, for one, has developed scaffolding guides for English learners. The school district in San Diego has translated all of the standards into Spanish. The Council of the Great City Schools released a “user’s guide” for districts looking to find instructional materials tailored to English learners’ needs this August.

In 2013-14, 35 percent of Denver’s public school students were English learners.

District chief schools officer Susana Cordova said the new standards highlight an already-existing challenge: “It’s difficult to find material in Spanish in general–and even more difficult to find material that’s been revised and aligned to the rigor of the Common Core.” The district offers several Transitional Native Language Instruction, or TNLI, in programs, in which Spanish speaking students spend some time learning in their native language.

She said there also aren’t enough materials with features that make it easier for students who are learning English to process text (such as on-page definitions for tricky words). She said the Common Core standards’ emphasis on informational text and problem solving in math means that English learners are confronted with more technical language and, in math, just more language than ever before.

And even resources that are advertised as aligned don’t always live up to the hype, she said. When the district reviewed one publisher’s Common Core-aligned materials, Cordova said, eight of the ten lessons built for English learners focused on idioms. “That’s not the bulk of what English learners need to learn,” Cordova said.

The district adopted a new program called E.L. Achieve, intended to be a more effective literacy program for English learners, earlier this fall.

At Ellis Elementary, where more than 24 languages are spoken and fewer than a third of students speak English as a first language, “we didn’t get the new standards and think, oh my goodness, how will we teach our English learners,” said Linda Miller, the dean of instruction at Ellis. “It was, how will we get STUDENTS to show that they have mastered or are where they should be with the standards? So now it’s this aftermath—so now we’re going to use E.L. Achieve. How will that support teaching the standards as well?”

“We’re working as hard as we possibly can to teach all our students,” Miller said. “A large majority happen to be English learners. But that hasn’t changed.”

Teachers were most concerned about how students, especially English learners, would fare on PARCC, the state’s new computer-based, Common Core-tied assessment, which, they said, is very text heavy. Even the instructions for how to navigate the online exam—drag and drop, or figuring out which box is an answer box—can trip up students, especially those who are still translating in their heads.

“A lot of our English learners are brilliant,” Winslow said. “But the test isn’t really going to show you what they’re capable of. And then it looks like we’re not doing our jobs.”