When Ron Sally moved to Denver in 1995, he bought a home in the Park Hill neighborhood in part because he wanted to live within the East High School attendance zone so his young children could one day attend the city’s flagship high school.

A decade later, when his eldest son was in eighth grade, Sally, a 51-year-old corporate lawyer, looked at East more closely and backed away fast.

“In hindsight what I realized was everybody I had talked to about East was white,” said Sally, who is African American. “Then I dug a little deeper, did my due diligence, talked to current and former students, current and former parents, experienced teachers, and they were universal in their concern about the challenges they thought (my son) would be facing at East, as an African American male coming from a family that had high aspirations for him.”

So Sally enrolled his son instead at Colorado Academy, one of the Front Range’s priciest private schools. The lad thrived at CA and went on to Princeton University.

What Sally saw that alarmed him so was evidence of distinctly different school cultures and educational outcomes for kids of color and low-income students at East compared to their white, more affluent peers.

Although the achievement gap is endemic in schools and districts across the nation, it is especially glaring in high schools like East, of which there are dozens in cities and suburbs from coast to coast. These are the schools that look integrated from the outside, but are in fact segregated inside classrooms.

In such schools, top-performing students, most of them white or Asian and on the more affluent side, take honors and Advanced Placement classes and regularly gain admittance to the nation’s elite colleges and universities.

Meanwhile many African American, Latino and Native American students, predominantly from low-income families, fare far less well, tracked by their academic history into “regular classes” where expectations are lower and the pace of teaching and learning much slower.

Over the past decade, successive East principals and true-believing teachers have worked to narrow the gap with several initiatives, including:

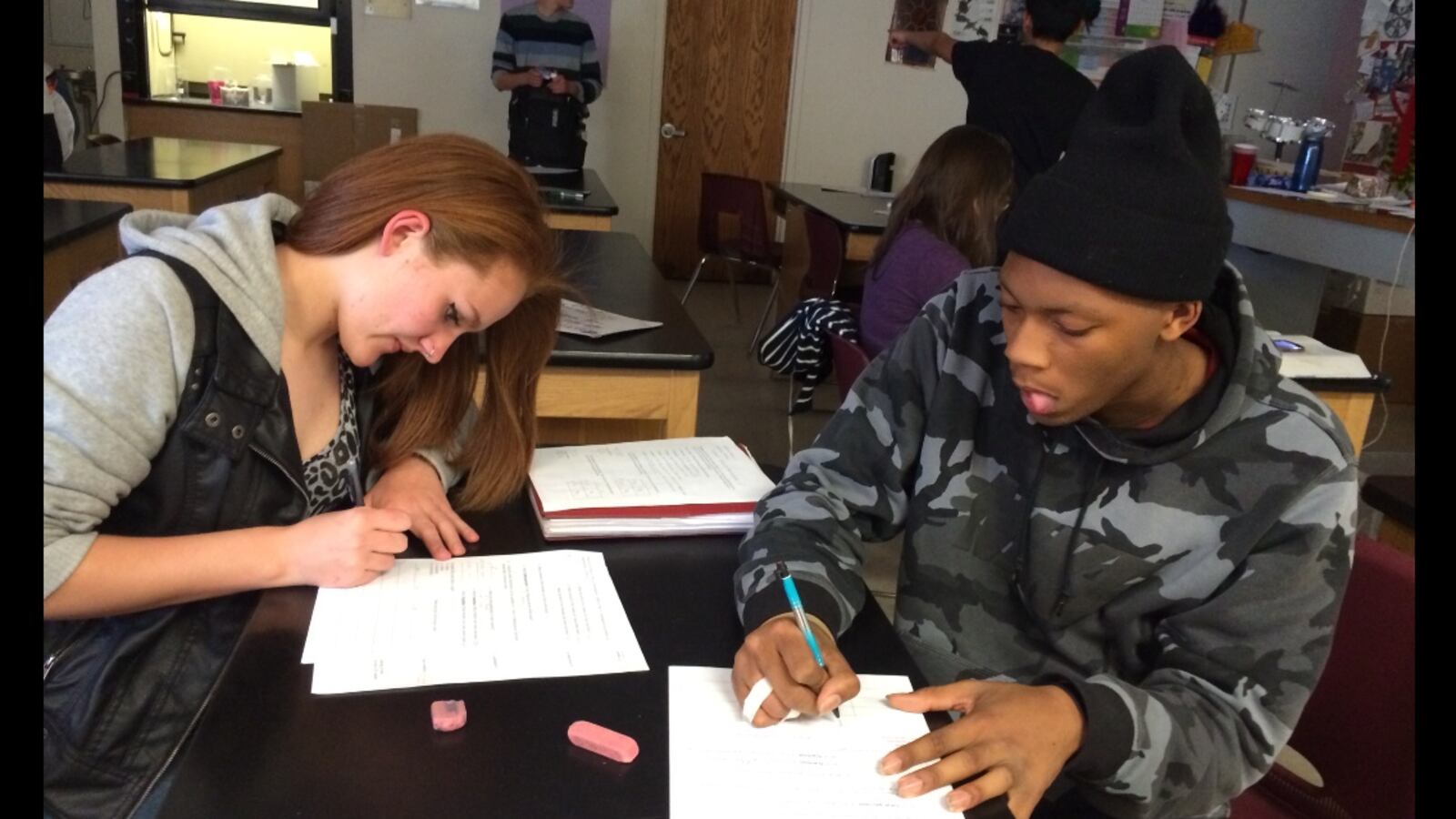

- launching “detracking” efforts to bring honors and regular-track students into heterogenous classes and providing extra academic support classes for the lower-performers

- raising awareness among students of color and their parents about the availability of honors and AP classes

- identifying high-achieving minority students in regular classes and urging them to challenge themselves academically with tougher classes.

In addition, a school-based foundation provides low-income students with funds to buy AP books, and pays for AP exams for those who cannot afford the $89-per-exam fee.

A small drop in a cavernous bucket

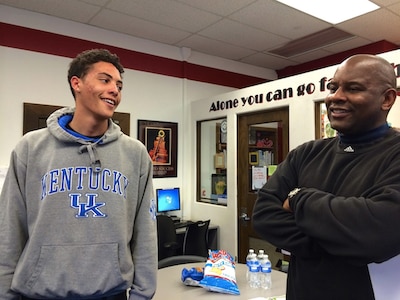

Although Ron Sally decided not to enroll his son at East, the school’s gaps gnawed at him, and in 2009 he founded Project Greer Street, a mentoring program for African American male students at East. Its aim is getting students with unrealized academic potential through high school and into elite four-year colleges. His program has helped all of its graduates attend top-tier four-year schools.

“I’m from St. Louis, where the inner city schools look nothing like the palace we’re in right now,” Sally said on a recent Saturday, seated in a spacious East classroom with enormous windows. “So when I came to Denver and people said this was an inner city high school I said, ‘this is Xanadu, compared to where I’m from.’ I thought to myself, if this can’t work in a place like East, which I think is a fantastic high school — it’s like a Benneton commercial, as far as student composition — then we’ve got a real problem here in America.”

But Sally is the first to admit that his project, which this year serves seven juniors, amounts to a small drop in a cavernous bucket.

And despite determined efforts by Sally and a dedicated core of East teachers, backed by administrators, progress has been painfully slow and decidedly mixed.

On the one hand, minority student participation in AP classes is on the upswing, thanks in large part to a concerted, nationally-recognized effort by a student-led initiative called Angels for AP Excellence. Even as a more diverse group of students take AP classes and exams, exam passing rates have not dipped at East.

On the other hand, a much higher proportion of white students pass AP exams than do African Americans or Latinos. Last year the AP exam pass rate among white students was 65 percent. Among African Americans it was 35 percent, and among Latinos it was 47 percent.

Also, gaps measured by the state TCAP test remain yawning, wider than the gaps in Denver Public Schools as a whole between white and minority students.

Still, the breadth of East’s TCAP gaps may be explained in part by how high-achieving East’s top students are. In fact, East’s minority students outperform their counterparts across the district even though the gulf between them and East’s white students is so huge, as measured by standardized test scores.

At East, for example, the gap between white and African American ninth and tenth graders on math TCAP tests in 2013 was 51 percentage points – 68 percent of white students scored proficient or advanced on the tests compared to 17 percent of African American students. The gap across DPS on those same tests was 41 points.

But the district gap was smaller mostly because just 56 percent of white students DPS-wide scored proficient and advanced. Fifteen percent of African American students were proficient or advanced in math across the district.

Unlike DPS as a whole, gaps between white and Latino students are narrower at East than between whites and African Americans. Teachers, administrators and advocates speculated that this may be because a large number of East’s Latino students “choice” into the school, while many African American students live within the attendance boundaries and therefore don’t have to make an affirmative choice to attend East.

Other data are mixed as well. Across racial and ethnic lines, on-time graduation rates at East are relatively high – 93 percent for whites, 89 percent for African Americans and 85 percent for Latinos. Dropout rates are extremely low – under 2 percent for each group.

But there are significant disparities in percentages of students requiring remedial course work in college. Among East’s white graduates, 13 percent require remediation. That number climbs to 45 percent for Latino graduates and 67 percent for African Americans.

Attacking the gap

Anyone serious about attacking the stubborn challenge of achievement gaps has to take a long view, according to Andy Mendelsberg, East’s current principal.

“Nobody is changing achievement gap stuff significantly over one year,” said Mendelsberg, who has worked at East for 16 years, the past three as principal. “It’s got to be a prolonged effort. We are impatient to close the gap, but we’re patient in the things we’re putting in place to achieve the desired goals.”

The attitude toward the gap at East has shifted over the past decade from something like complacence to a school-wide fixation on tackling the issue head-on, Mendelsberg said.

“When I was dean here [in the late 1990s] I would have told you that I never understood why everyone thought East was such a great place,” he said. “I thought it was great for one kind of kid but I didn’t think it was great for every kind of kid walking in the door.”

Today, Mendelsberg said, “I would tell you we are still a long ways from any kind of trumpeting success. But we are all unbelievably aware of the gaps, we all know what role we have to play to help kids close those gaps. We just know it’s going to take time.”

Some teachers in the trenches, though, said they wish the school would be more strategic in its gap-closing efforts. Jessica Donovan-Massey has taught English at East for nine years. She, along with a group that also includes science teachers Margaret Bobb, Bonnie LaFleur, and Nate Grover, are among the teachers at the heart of the effort to place students in untracked, heterogeneous classes.

A key component to making mixed classes work is academic success classes, which provide extra learning time to all students who wouldn’t normally be in an honors class. To be effective, these classes need to be small, teachers said, but they keep growing in size, demonstrating a lack of understanding of their importance among the administration.

Also, for mixed classes to work well, Donovan-Massey said, the school needs to pay attention to research that says a mixed class should have balance of at least 60 percent higher-achieving, more affluent students and no more than 40 percent lower-performing, usually lower-income students. She describes the split as between “high-achieving students and reluctant students.”

Instead of using the 60-40 split as an outer limit, Donovan-Massey said, East administrators, those who are even aware of the research, use it as a norm. Given the slippage that invariably occurs, she said, this means that many heterogeneous classes are skewed closer to 60-40 in the other direction.

“Let’s put it this way,” she said. “It is very hard to rally that kind of a class behind you, which is what you need to do: rally them behind you in academic pursuit. And they are reluctant to rally behind you because they don’t believe; they’ve been mistreated, they’ve been put down, they’ve been marginalized, and so when you have a whole bunch of them, like a whole class full, it’s a critical mass in the wrong direction.”

Getting strategic

It helps when developing strategies for attacking achievement gaps to recognize that they are multifaceted, said Christine Miller, East’s parent and community liaison.

“The achievement gap is linked to two things: a knowledge gap and an advocacy gap,” Miller said. “A lot of students of color here don’t have the knowledge of what’s available, and their parents don’t either. But they don’t know how to advocate for themselves or their children either. When you are lacking in those two things you end up being tracked.”

Students confirmed this. Ray Pryor is a high-achieving, African American East junior who attended the Odyssey charter middle school and who belongs to Ron Sally’s Project Greer Street. He entered East feeling academically prepared for any challenge. He immediately enrolled in freshman honors-level courses, where he thrived. But he knew nothing about the next logical step.

“I had no idea what AP was until a counselor made me aware of the opportunity” during his freshman year, Pryor said. “And once I learned about it, I said why not, because I said why not to honors classes and I felt it would be the most enriching academic experience I could have at East.”

Pryor is now an active member of Angels for AP Excellence, the student-led group promoting broader AP participation. This school year, he and some of his peers have presented their program before the College Board, AP’s parent organization, and at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Kate Greeley is in her second year as an assistant principal at East, and serves as a staff liaison with the student AP advocacy group. Before coming to East she worked as a data specialist at DPS headquarters, and she has brought a data geek’s focus on numbers to the school’s gap-closing efforts.

“[The gap] is not being swept under the rug,” she said. “It’s not like we say ‘oh that’s shocking’ and then move on with our day. Instead we have tried to take the approach of, ok it is shocking, now what are our action steps?”

The first step Greeley and her team took last school year was identifying students of color who had scored proficient or higher on the TCAP reading exam and who had a grade point average of 3.0 (B) or above but were not enrolled in high-level courses. There were about 100 such students. Christine Miller sent letters home to those families. Many responded, like Ray Pryor, that they had never heard of AP. And if AP provided college credit and could help them save tuition money, and their kids were ready for it, by all means sign them up.

Students were invited to meetings led by Angels for AP Excellence to demystify AP, and had the opportunity to shadow students into AP classes.

Greeley’s next move was to dig down one layer deeper and find last year’s ninth- and 10th-grade students of color who had scored partially proficient on the TCAP and weren’t in high-level classes – 324 in all. Last fall, East staff reached out to those students and their families to offer them counseling and informational sessions on college admissions, ACT testing, and test-taking strategies. Of those invited, 131 have participated in informational events and counseling sessions.

How many of these students decide to take higher-level classes will become clearly when the 2014-15 school year begins. But last year’s efforts yielded some big gains. The number of African American students enrolled in AP classes increased this year at East by 36 percent. Latino student AP participation climbed by 26 percent.

Still, the AP participation rate by ethnicity is nowhere near mirroring the composition of the school’s student body. White students are over-represented in AP classes, while African American and Latino students remain significantly under-represented.

Breaking through the discomfort

Ask kids of color at East and they’ll tell you that honors and AP classes don’t always feel welcoming to them, and it requires some courage to cross the threshold for the first time.

Senior Karina Orellana decided as a junior to take an AP government and politics class. She and her friend Luis Cotto enrolled together. The first days especially were tough.

“We walked in and right away the minorities (four out of a class of about 15) all sat together and everyone else sat on the other side of the room,” Orellana recalled.

And even after she started feeling more comfortable, there would be awkward moments. When class discussion turned to immigration issues, “everybody just turns around and looks at the little Hispanic girl expecting me to say something about immigration because I am Hispanic.”

Orellana and Cotto are now leaders of the Angels for AP Excellence group.

Ray Pryor took AP human geography as a sophomore and experienced the same self-segregation of students. Then the teacher switched up the seating chart and forced students to mix.

“I think it was best for me not to get used to this comfortable enclave in the minority corner,” he said. “I got to meet some fantastic new people who come from a different culture than I do.”

It’s easy at a school like East for white students to remain in their bubble and remain oblivious. White senior Sarah DeMoully, who is a leader of Angels for AP Excellence, said she was unaware of the achievement gap until a friend who writes for the school paper did a story on the issue and DeMoully accompanied her during some of the reporting process.

“Honestly, before that my awareness was zero,” she said. “When you are in a classroom with kids who just look like you, the awareness just really isn’t there because you are comfortable.”

Until she attended a meeting with her reporter friend, “I hadn’t heard how some students can feel uncomfortable in classrooms, and that was really eye-opening to me and I knew I wanted to do something to help change that.”

Eliminating the gaps will be a long-term struggle, Pryor said, because inertia comes from both sides of the chasm.

“In American society, conformity is very comfortable. It’s OK to fit in the groups society says you belong in,” he said. “I think that’s a huge challenge when you come to a school like East where you have so many kids from different groups that have been conforming for a majority of their lives. How as a school do you ensure success for everybody when you have people coming from all these backgrounds?”

Schools like East will continue struggling with that question into the indefinite future.

Editor’s note: For a deeper look at some of East’s – and other schools’ – achievement gap data, see this story.