For more than two decades, the Colorado State Board of Education has had the final word on disputes between charter schools and the school districts that authorize them.

A bill expected to be introduced soon in the Colorado General Assembly would change that by allowing appeals to district court. State Rep. Shannon Bird, the bill’s sponsor, said she wants to provide an independent review in a process that has often been perceived as political.

“If there is a dispute, the parties in the dispute should have an opportunity for review if they believe the laws have not been applied fairly,” she said. “To me, it is fundamental.”

Bird, a Westminster Democrat, said her bill is not “anti-charter.” Nonetheless, it represents the first test this session for how the current Democratic-controlled legislature views the balance of power between districts and charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently operated.

Some school districts are applauding the potential change, while charter leaders fear they would be at a disadvantage if disputes over whether a school should be approved or receive a renewal of its contract were to go to the courts.

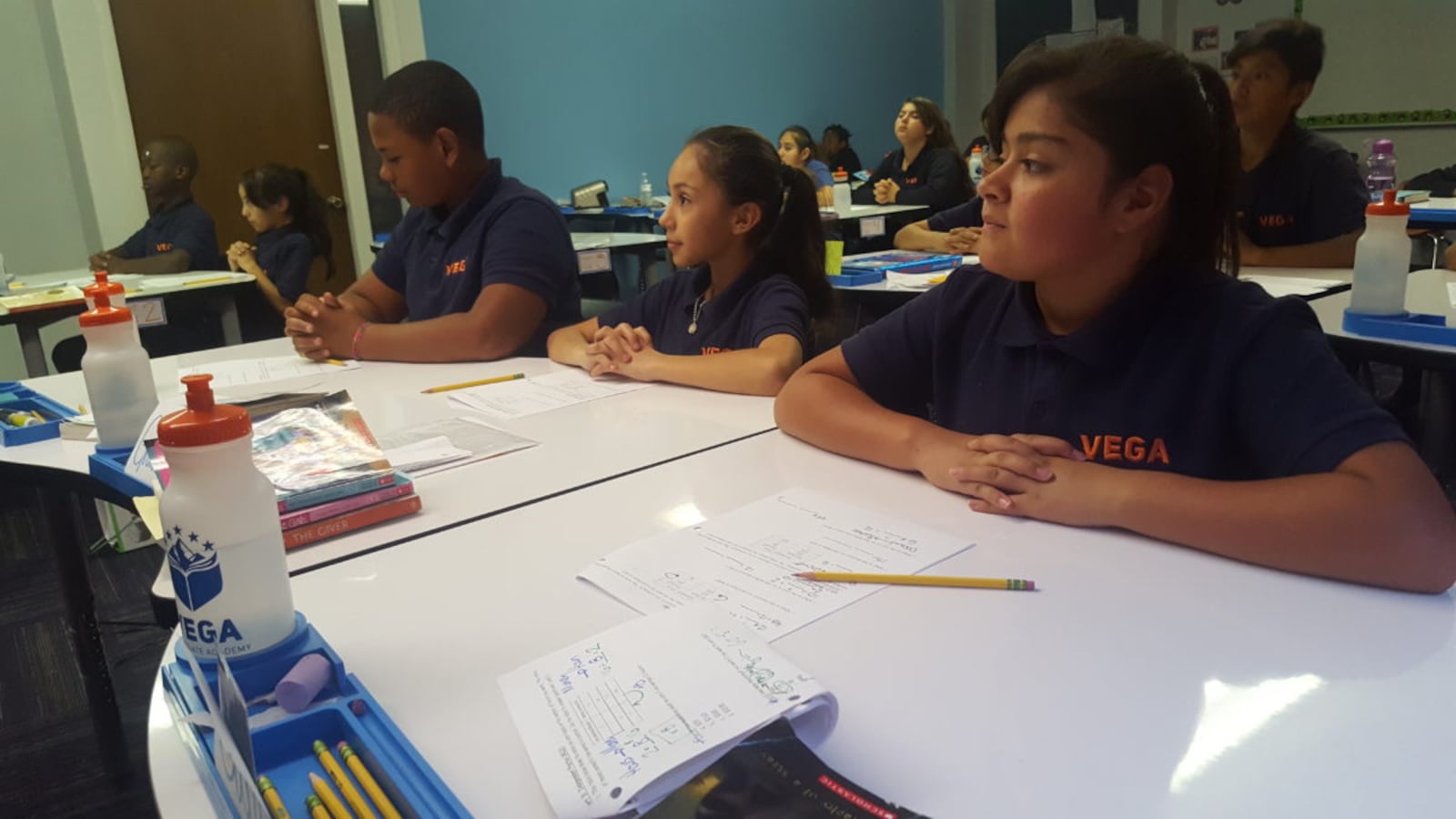

“As a small charter we don’t have the resources that a district does to put into a legal battle,” said Miguel In Suk Lovato, vice chair of the board of Vega Academy, a charter school that was recently involved in a dispute with the Aurora school district. “I think it would have stretched us to the limit and maybe the breaking point.”

Aurora Superintendent Rico Munn, meanwhile, believes the opportunity for appeal would make the process fairer.

“It’s an option for many decisions of administrative agencies,” said Munn. A former member of the State Board of Education, Munn said he doesn’t understand why its decisions should be different.

State laws limit the grounds that school districts can use to turn down a charter proposal. If a local school board rejects an application or renewal request, the charter school can appeal to the State Board of Education, which can either uphold the district decision or send it back. Charters schools can appeal again, with a second State Board decision being final.

The State Board of Education consists of seven elected, partisan members, but in charter school appeals it often doesn’t split along party lines. In the past decade, the State Board has upheld local board decisions 13 times and sent them back for reconsideration 18 times. In five cases, it’s ordered the establishment of a school against a local board’s wishes, and in three, it’s overturned a decision to revoke a charter.

The bill would also make existing non-discrimination requirements clearer and change other aspects of the appeals procedure, including:

- Making it explicit that charter schools must enroll students through random selection, with no consideration for disability, English learner, or gifted status

- Requiring charter schools to lay out exactly how they’ll meet the needs of special student populations

- Banning parties in a dispute from having contact with board members outside formal channels

- Requiring the State Board of Education to create a written record that lays out how and why it arrived at its decision.

The State Board of Education won’t take a position on the bill until after it’s introduced.

Many of the bill’s provisions don’t represent a dramatic change from current practice for most charter schools. For Bird, these issues of equity are important enough to make explicit in statute, but they leave some charter operators wondering whether they’re being held to a different standard than district-run magnet programs and options schools.

“What problem are we trying to solve here?” asked Dan Schaller of the Colorado League of Charter Schools.

As a whole, Colorado charter schools serve higher percentages of English language learners and students in poverty than the statewide average, but lower percentages of students with disabilities. Some parents of students with disabilities report being discouraged from enrolling their child, often because he’s not a “good fit” for the school’s educational model, while in other cases, districts tell charters they cannot enroll a student because the school doesn’t offer the right services.

The education of students with disabilities was at the heart of Aurora’s dispute with Vega. After the State Board overruled Aurora’s decision to shut down the school, the district allowed the school to keep operating provided it met certain conditions. An independent review found that Vega was not complying with all the requirements to serve special education students but also found fault with aspects of Aurora’s investigation.

Lovato said he believes the district and the school have a stronger relationship now, and Vega has improved its record-keeping for special education students. He’s not sure that would have happened if the two sides had ended up in court.

For her part, Bird said her bills aims to ensure charters fulfill their potential.

“We decided a long time ago in Colorado that charter schools are part of our family of public schools, and I believe in that,” she said. “They’ve done innovative things and opened doors of opportunity, and I want to make sure those doors of opportunity are open to all kids.”