A Republican State Board of Education member who believes socialism poses grave dangers at home and abroad has put his stamp on how Colorado students will learn about the Holocaust.

Over the last year and a half, Steve Durham has pushed for the state’s academic standards to connect the Holocaust and other genocides to socialism. Durham succeeded in omitting the word Nazi from an early version of the standards in favor of the party’s full name, the National Socialist German Workers Party.

Durham agreed to include the word Nazi after Jewish community members lobbied the State Board of Education — so long as the full name with the word socialist remained.

“People don’t know and have a right to know that this party was and is a socialist party,” Durham said at an August State Board meeting. “That is largely lost on the American people and on a number of history teachers as well. I oppose dumbing down the standards.”

Historians say Durham is wrong about the Holocaust and wrong about the roots of genocide. The idea that Nazis were socialists is “a lie,” according to David Ciarlo, a University of Colorado history professor who studies German politics. “It’s completely wrong.”

Still, Durham has exerted outsized influence over the standards related to genocide, which are meant to guide teaching across Colorado. A key section largely authored by Durham overrides recommendations from a committee of teachers and experts. The approved standards drop references to genocide in Rwanda, for example, while adding detailed references to the Communist Party of China.

The standards as written “absolutely suggest to teachers that they should be making a connection” between genocide and socialism, said John Gallup, a history teacher in Jeffco Public Schools who recently returned from Auschwitz as part of a fellowship on teaching genocide and reviewed the standards at Chalkbeat’s request.

Durham’s sway, despite his misleading historical claims about the Holocaust, raises questions about the State Board’s ability to accurately referee conflicts over teaching history as its members tackle a contentious update to the broader social studies standards — and at a moment when those fights are erupting nationwide. And in a state where teachers have limited access to Holocaust-specific curriculum or training programs, some see the attention being paid to socialism as a disturbing distraction.

“It feels very antisemitic, quite frankly,” said Democratic state Rep. Dafna Michaelson-Jenet, co-sponsor of legislation requiring Holocaust education statewide. She sees the latest standards as an effort to score political points rather than teach about the murder of Jews and other minority groups. “You’re erasing the violence that happened by making it something that it wasn’t.”

The Holocaust becomes contested territory

The meaning and memory of the Holocaust have become yet another battleground in the fight over what students should learn about history, race, and gender. A Texas school administrator told teachers to balance books on the Holocaust with “opposing views.” A Tennessee school board voted to remove the acclaimed graphic novel “Maus” from its curriculum due to its “unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide.”

The Holocaust also remains a potent symbol of evil to be used — or misused — in political arguments. Opponents of vaccine mandates have donned yellow star badges similar to those the Nazis forced Jews to wear. At a rally last year, Republican congresswoman and conspiracy theorist Marjorie Taylor Greene linked the Nazis and today’s Democratic Party by describing both as “national socialist parties.”

But teaching the Holocaust wasn’t supposed to be divisive in Colorado.

A state law passed in 2020 with broad bipartisan support required that students learn about the Holocaust and other genocides before graduating high school. (Many schools already included the Holocaust in history and literature classes, but it was not a requirement.)

Following the legislation, a committee of experts and teachers prepared recommendations for what students should learn. When the Democrat-majority State Board received them in spring 2021, Republicans raised a host of objections, many driven by contemporary political concerns — a theme of the discussions that would take place over the next year.

Republicans objected to references to mass violence, for example, saying the standards should then also reference recent violent protests in Portland, Oregon, and Seattle following the murder of George Floyd.

Durham saw something else wrong with the recommendations. While they mentioned the Cambodian genocide, they were silent on the crimes of the Soviet Union and Communist China. He proposed adding these events and said the standards should name the governments — such as the National Socialist German Workers Party — that carried out genocides.

Board Chair Angelika Schroeder, a Democrat, was largely silent on the substance of these discussions and later declined an interview request. She and fellow Democrat Rebecca McClellan ultimately voted with the Republicans to adopt Durham’s proposal, with McClellan praising the inclusion of the oppression of the Uyghurs.

Durham also proposed that students discuss the question: Why are so many modern genocides associated with socialist and communist governments?

That question didn’t make it into the standards — his colleagues simply ignored it — but Durham said in an interview, “I hope that students make that connection.”

Critics say they agree that students should learn about genocides carried out by the Soviet Union and China, but they worry that Durham’s list distorts history by excluding many other examples. Durham isn’t interested in that argument.

He dismissed Michaelson-Jenet’s concerns as playing the “race card.” Informed that many scholars disagree that socialists are the only source of genocidal violence, Durham asked a reporter, “Do they miss Pol Pot?”

Durham challenged the reporter to name any genocides committed by regimes that weren’t socialist, then rejected any examples as not truly conservative.

“There is some truth out there that students need to understand,” Durham said. “Weak government, limited government cannot engage in this kind of activity. Socialism by definition is big government. It doesn’t mean that they all commit genocide, but they are the ones capable of it.”

Experts say Durham’s ideas are incorrect

Historians and educators say Durham’s comments and the emphasis of the standards he crafted are misguided. They say it’s important for students to understand that governments of all stripes have committed genocide. It’s also important for students to understand that mass murder often starts with words that dehumanize and demonize.

“Genocide is carried out by leftist governments and governments on the right, and it is not just a crime carried out by authoritarian states or dictatorships. Democracies have carried out genocides,” said University of Northern Arizona professor Alexander Alvarez, a genocide scholar who serves on his state’s task force charged with improving Holocaust and genocide education in K-12 classrooms.

“If we think genocide is just carried out by communist governments, we don’t have to look at our own history, or we can think that we are immune to the forces that lead to genocide.”

Seeing the term socialism through a modern American lens is also a mistake, historians and educators said.

The Nazis rose to power as a racist right-wing party virulently opposed to socialism and communism, according to historians interviewed by Chalkbeat and resources provided by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. The first concentration camp, Dachau, opened in 1933 to house political prisoners, many of them communists and social democrats.

In 1920s Germany, the term “national socialism” represented a kind of racist populism that put the interests of ethnic Germans above others. The term stood in contrast to “international socialism” and “international capitalism,” both of which were associated with Jews to falsely blame them for harming the German people. While an early Nazi party platform included some socialist ideas, leaders soon ignored them and those ideas became irrelevant to the party’s rise.

“What’s important is that they demonized their opponents,” Ciarlo said.

Through a letter-writing campaign and in private meetings with board members, Jewish groups raised concerns that the initial version of the standards adopted in 2021 without the term Nazi missed the mark. Most students have heard of Nazis before they encounter them in history class. If students then learned only about the National Socialist German Workers Party, would they understand the party’s defining ideology was belief in German racial superiority that justified killing or enslaving other peoples?

“It’s essential that when they hear the term Nazi they connect it to a genocidal society,” said Dan Leshem, a Holocaust educator and director of the Colorado Jewish Community Relations Council. “We need to be horrified and shaken and shook.”

Compromise keeps ‘a piece of indoctrination’

This year, the State Board had another shot at the standards covering the Holocaust and genocide. The entire social studies standards are up for review, and the standards committee recommended new language in June that included the Soviet Union and China along with Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur — without the emphasis on socialism so important to Durham.

Democratic board member Karla Esser said she heard the concerns of the Jewish community and shared them. She brought an amendment in August to describe the Holocaust as “carried out by the German Nazi Party and its collaborators.” Esser and McClellan also pushed back during a board meeting when Durham said the Nazis were socialists.

Esser’s amendment was adopted unanimously by the State Board. Alongside the addition of the term Nazi, it restored much of Durham’s socialism-focused language and replaced the simpler language the committee had recommended.

In an interview, Esser said the language was a compromise, one she felt confident could get at least four votes on the seven-member board. She knew Durham felt as strongly about having the word socialist in the standards as she did about using the word Nazi.

“That is his belief,” Esser said. “In my estimation, it’s a piece of indoctrination. I don’t think the standards should reflect our worldviews. They should reflect recorded history, with the understanding that there is always a point of view in history.”

But Esser gave Durham credit for listening, and said she doubted his interpretation would reach students. “Most teachers and most textbooks are not going to try to indoctrinate our students,” she said.

Michaelson-Jenet, the legislator, said the result ignores the intent of the bill requiring Holocaust education. The goal was to equip young people with basic knowledge about the Holocaust, something she saw many people lacked during her time leading the Holocaust Awareness Institute at the University of Denver, and teach them how intolerance can turn into genocide.

Yet State Board members also seemed to lack a basic understanding of how genocide happens, she said, and they didn’t consult experts who could have informed their decisions.

“If we want to actually get to the point where we’re teaching what hatred looks like, this is not the way to do it,” she said. “I don’t see anything about that goal.”

What does this mean for students and teachers?

The compromise language agreed on by the State Board is part of a broader update to Colorado’s social studies standards set to be finalized in November. In the next few weeks, the same State Board will consider new civics standards and whether to expand references to the contributions of communities of color and LGBTQ Americans, as required by a state law passed in 2019.

State standards represent what Colorado students are supposed to know and what Colorado schools are supposed to teach. But school districts also have broad discretion to make their own choices. Durham, a big believer in local control, is quick to say no teacher has to follow his lead.

Gallup, the history teacher in Jeffco Public Schools, said he’d be surprised to see school districts formally adopt Durham’s political framing. “I think teachers will look at this, and to be honest, they’ll use that language as they see fit and they’ll make that choice in their own classroom,” he said.

School districts have until July 2023 to incorporate the new genocide standards into an existing course required for graduation. The state is developing an online resource library to help.

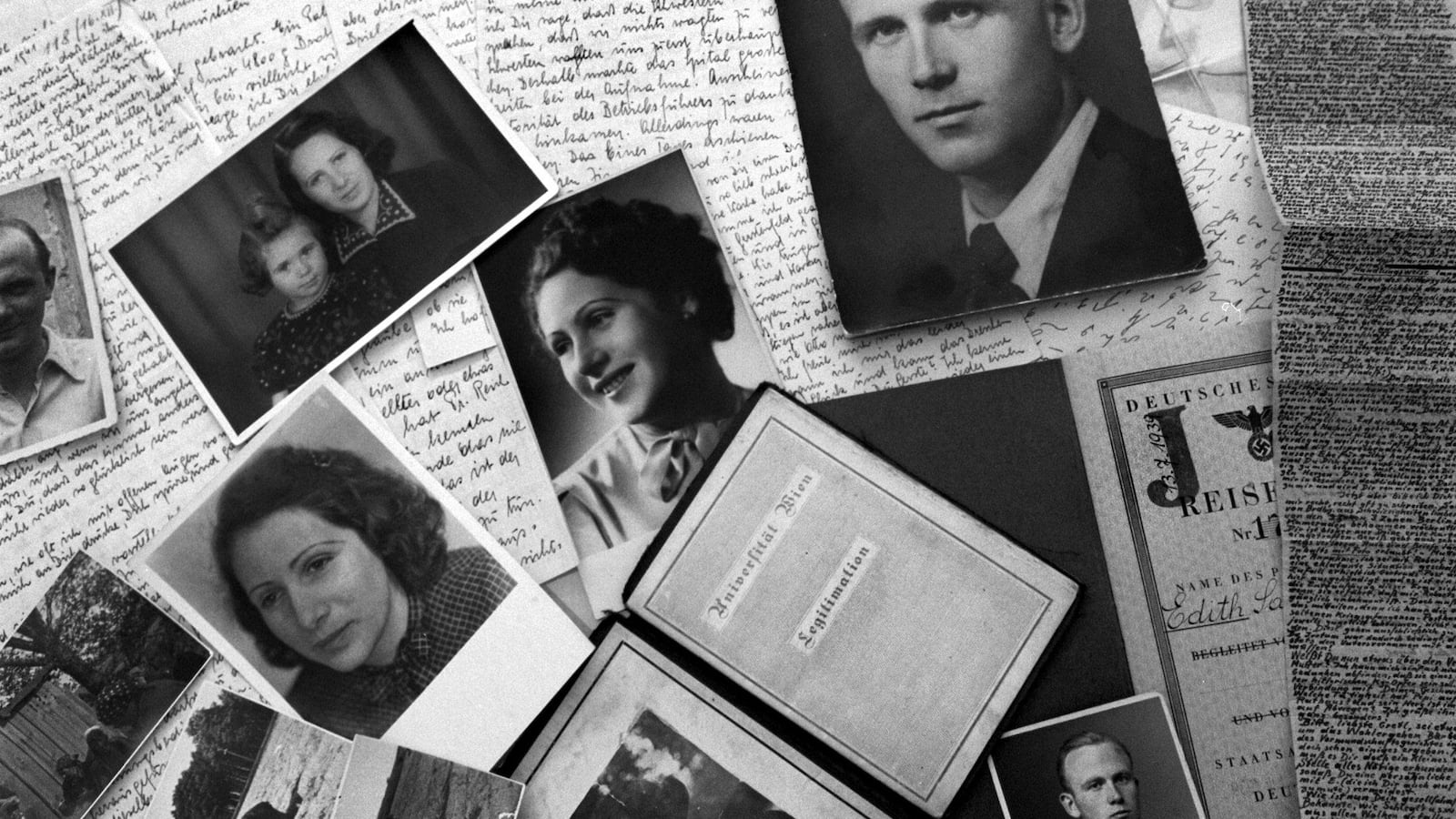

Leshem said his focus now is ensuring teachers have the resources to teach the topic well. Recent surveys show a disturbing ignorance about the Holocaust among younger Americans, even in states that mandate genocide education. And every year, there are fewer survivors left who can share first-hand accounts. Colorado also lacks the museums, the teacher training programs, the funding, and the well-developed curriculum on the issue that other states have.

The goal of Holocaust education is ultimately genocide prevention. Ciarlo asks his students: “We all know that Nazism should never happen again because of the Holocaust. There’s a lesson there. What’s the lesson? What should not be repeated?”

History does not offer easy answers. Demonizing minority groups and political opponents proved an effective way to gain power. Millions of Germans found the Nazis’ extremism alluring, and millions more looked the other way as their neighbors were murdered. The Nazis were not defeated peacefully, and genocides continue to happen around the world.

The Holocaust needs to be placed in historical context, not twisted to fit our own, educators said. At the same time, students should be able to see commonalities among genocides and make connections to our own society. Doing so will make us better, Leshem said, especially in a time when immigrants are being demonized and there is pressure to look away from the uglier aspects of American history.

Students should also understand the Holocaust was not carried out by monsters, but by ordinary people who had within them a common capacity for cruelty, Leshem said. Many of us have that same capacity, but we don’t have to act on it.

Gallup said that’s a lesson he took home from Auschwitz, where guides made a point of presenting the camp guards as human beings who “got up in the morning and put their pants on one leg at a time.” So were the Germans who resisted in ways large and small. And that’s the lesson he plans to emphasize for his own Jeffco students.

“The kids just have to see that, that people made choices,” he said.

Bureau Chief Erica Meltzer covers education policy and politics and oversees Chalkbeat Colorado’s education coverage. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.