An Airsoft replica gun is one of the reasons Andrew Pillow wanted to study the disparity in discipline between black and Hispanic students and their white peers.

A middle school social studies teacher at KIPP Indianapolis charter school, Pillow remembers seeing a black student expelled for bringing the real-looking — but harmless — gun to school and wondered if the average white student with a fake gun would have been disciplined so harshly in most schools.

The stakes are high in a school system where kids who are expelled, or even suspended, are much more likely to drop out of school.

“Who’s going to take a kid who was suspended for bringing a ‘weapon’ to school?” Pillow said.

So Pillow and three other teachers set out to research the racial divide in school discipline.

Sponsored by the Indianapolis chapter of Teach Plus, a national school reform organization that trains teachers to be policy advocates in seven states, Pillow and his partners showed off their findings Wednesday as part of a Teach Plus showcase.

They identified studies that showed only about four in 10 public school students nationally are black or Latino but more than two-thirds of suspensions and expulsions are of black or Latino kids, usually boys.

“We’re finding out that teacher language can drive that,” said Chelsea Easter, a middle school English teacher at Indianapolis Lighthouse charter school who was on Pillow’s team.

“Based on race or socioeconomic issues, if they have a preconceived notion in their minds that these types of kids behave one way and these kids behave another way, it’s kind of like a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

In all, more than 40 teachers used the showcase to present the research they’d done either on policy issues or on school leadership teams, identifying problems and offering solutions.

Pillow and Easter and their partners highlighted strategies to promote fairness in discipline including one called Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support, which relies heavily on data to help teachers better track and understand both good and bad behavior by their students.

Another group that presented Wednesday has already implemented a version of that disciplinary system in their classrooms at School 44, located northwest of downtown.

Perhaps the most important tool the teachers there use is a free iPad and smartphone application called Class Dojo.

All of the teachers and students at the school have iPads and use the app to instantly reward or penalize students, who can see on their iPads when they have points awarded or taken away based on their behavior.

“Suppose this student earns a compliment from another teacher in the hallway,” teacher Megan Bouckley said. “She gets a point for that and it shows up on her name. If that same student chooses to be out of her seat, she can lose a point for that. At the end of the day, you can view her report. It shows what her percentage is and what she lost points for.”

The app’s not just for teachers and students: parents can download it to their phones and watch their children earn or lose points — and the reasons why — in real time.

Some parents take almost immediate action.

“My classroom phone rings and a parent will say, ‘My child did what? Put them on the phone,’” Bouckley said.

The app helps promote closer collaboration. Other teachers can give points to students not in their classes. And teachers can communicate seamlessly with parents, who can send and receive messages through the app.

“You can send pictures, like ‘look how awesome you child is today!’” Bouckley said.

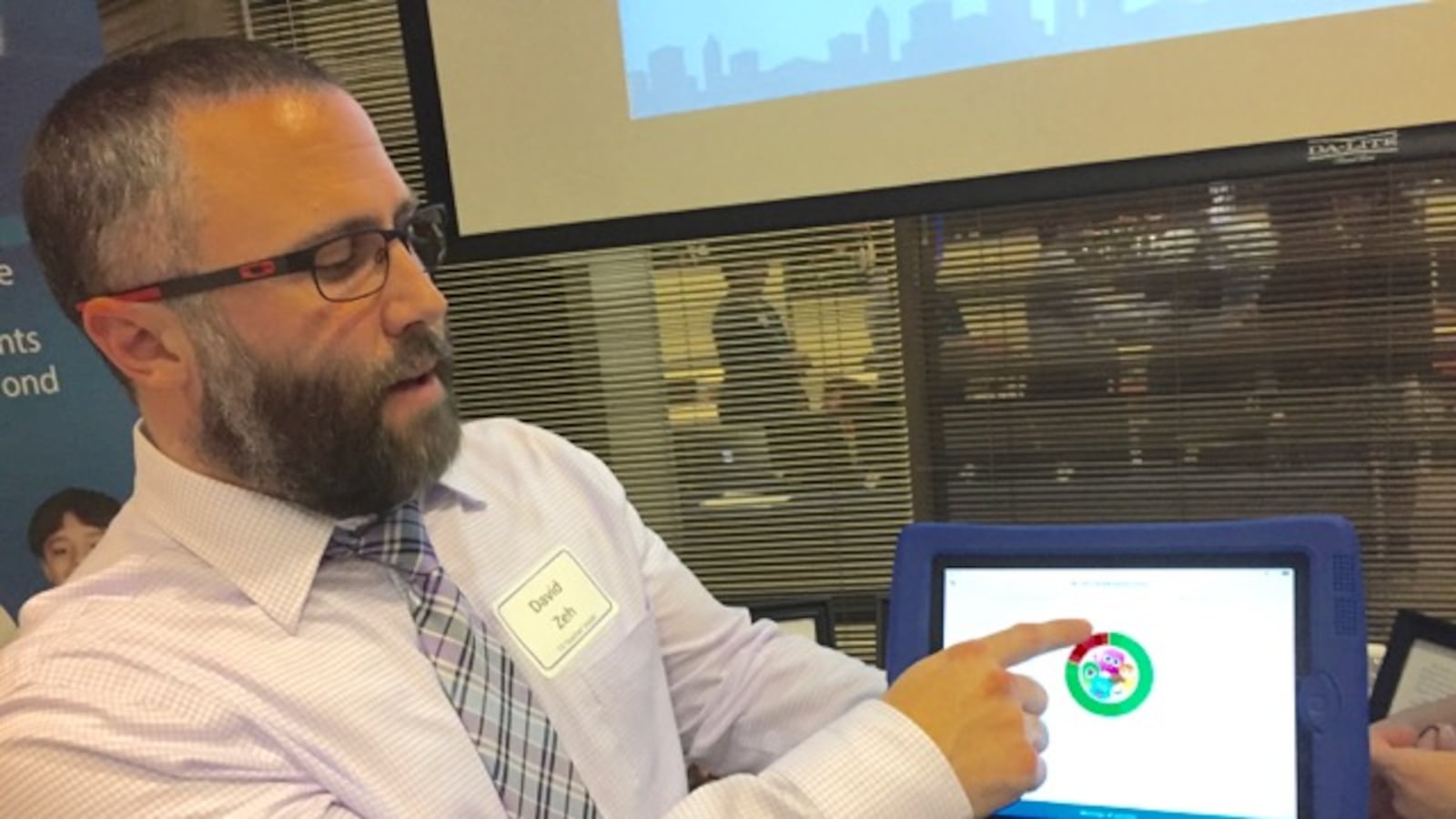

Teachers can also easily track student data, and see trends. Kindergarten teacher David Zeh, for example pulled up his class and showed 80 percent of his student feedback has been positive but he had recorded 652 negative behavior incidents, a number he wants to reduce.

“We’re trying to get more positive than negative,” he said.

The program showed that the biggest behavior issue in Zeh’s class is being “off task,” not surprising for fidgety kindergarteners.

But on the plus side, the program makes it easier for Zeh to record compliments for his students, which helps him remember to do that more often. And teachers are more aware of who is being disciplined, how often, what their main behavior problems are and what works to get them to behave.

On its own, this method isn’t likely to eliminate the kinds of racial bias that Pillow and this team identified but teachers who use the app say the ability gather data helps them pay attention to issues of equity and fairness. The data can show whether the same penalties are going to students for the same behavior, regardless of race or gender.

And that, Bouckley said, has ultimately helped lead to fewer extreme punishments.

“It seems to be working,” Bouckley said. “Our suspension are going down. We’re finding other ways of doing thing that keep them in the classroom.”