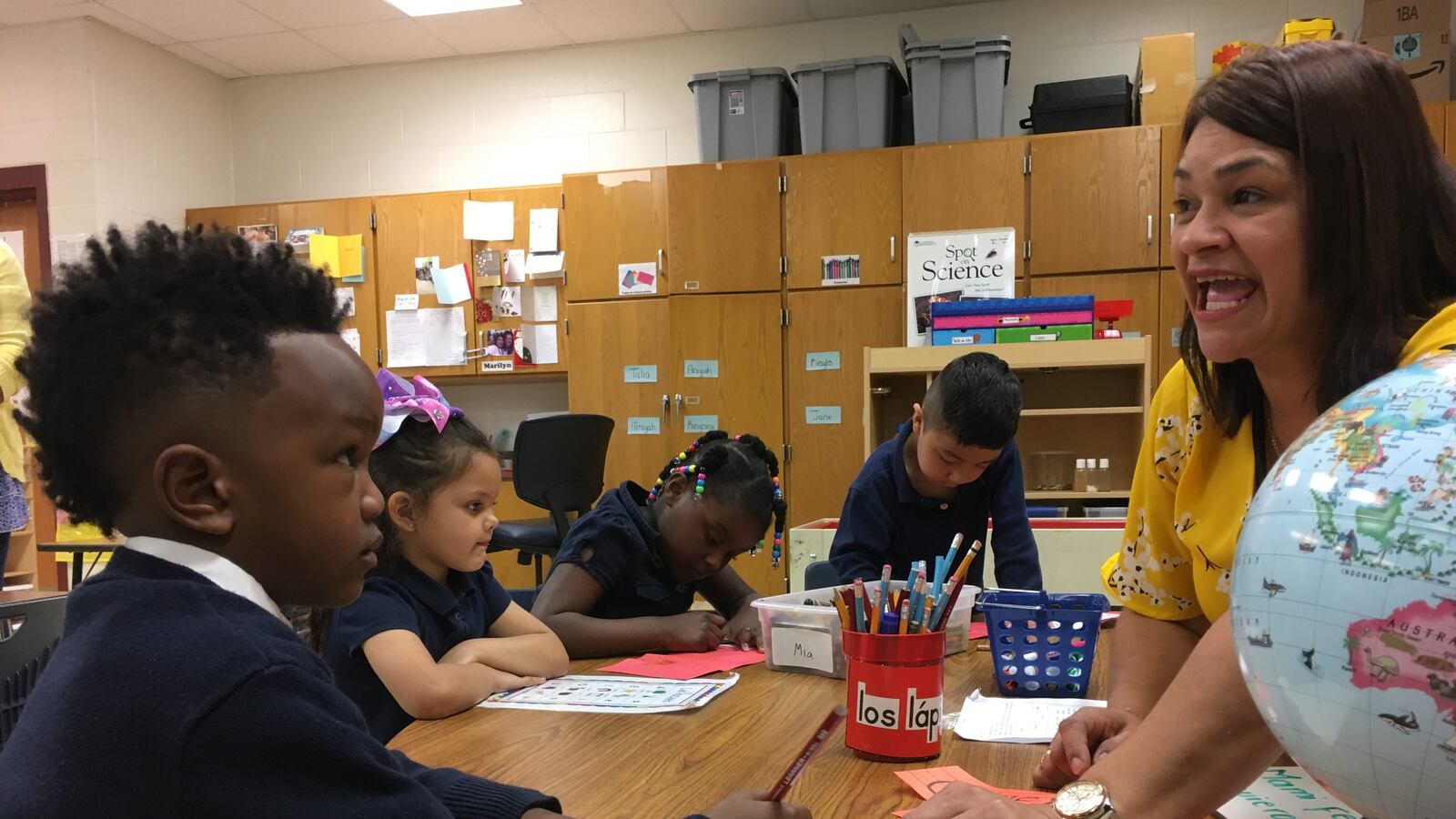

Sitting around a rainbow-colored carpet, preschoolers clamor to answer Maestra Maria’s question during the morning lesson on Earth.

What is there on Earth? They want to talk about las plantas y las flores, el agua y las frutas.

Maestra Maria deftly brings them back in line with a gentle reminder about what the students are supposed to do when they want to answer a question.

“Levantar la mano,” one student says. Raise your hand.

This year, Global Preparatory Academy at School 44 is starting children in its Spanish immersion program as early as it can, launching a new bilingual prekindergarten classroom.

It’s an unusual foray into pre-K for an Indianapolis charter school. Even as the state is putting more focus on early childhood education than ever before, the charter sector has been slow to reach 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds through pre-K.

Many charter leaders recognize the benefits of educating children during these critical developmental years and creating a smooth transition from pre-K to kindergarten, particularly those who serve mostly students of color and from low-income families in urban areas. But charter schools face significant challenges to offering pre-K, including a lack of a steady funding stream and a different set of rules and regulations for serving younger learners — and the fact that charters can, technically, only be K-12.

That’s pushing a handful of charter schools to look to creative partnerships in order to provide children with an earlier start to school.

Global Prep, which already partners with Indianapolis Public Schools as part of its innovation network of independently operated schools, works with the district to run its pre-K program. That way, the district handles licensing and funding, and students can attend for free.

In exchange, Global Prep can start its dual-language program one year earlier, teaching academic skills such as sounding out words and social skills such as sharing in both English and Spanish. Plus, students have the opportunity to stay in the same near-northwest side building from pre-K through grade 5.

“There’s a certain openness that kids have at age 4 to a new language,” said school founder Mariama Shaheed. “They just think school is supposed to be done in two languages.”

Jameka Robinson chose Global Prep over a private school for her 5-year-old son, Joshua, so he could learn Spanish. She hopes to keep him at the school so he can be both bilingual and biliterate: “Having a second language is a gift you can give to a child,” she said.

Other charter schools have sought out partnerships with private providers. Day Early Learning, which is run by the early education nonprofit Early Learning Indiana, has two pre-K classrooms at George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academy.

The classrooms run independently from Phalen, and Day Early Learning charges tuition or accepts state or federal vouchers. But the pre-K location helps both partners achieve a common goal: making sure children have access high-quality early education to get ready for kindergarten, said Erin Kissling, vice president of research and policy initiatives for Early Learning Indiana.

Anna Shults put a lot of thought into pre-K when she opened ACE Preparatory Academy three years ago but decided she didn’t have the capacity or skills to start a strong pre-K program.

This year, ACE Prep brought in an outside operator, Pre-K University. “Think of them as much as a subtenant as they are a partner,” Shults wrote in an email to Chalkbeat.

These partnerships work in part because pre-K can’t be part of schools’ charters. Charter agreements, by law, only cover grades K-12.

“We make it clear to our schools that we don’t monitor their preschool programs,” said James Betley, executive director of the Indiana Charter School Board, which oversees 25 charter schools throughout the state. “That’s not something we’re permitted to do, or something we want to do at this point.”

Charter schools could open their own pre-K programs, but they would have to go through a separate licensing process through the state Family and Social Services Administration.

Because Indiana does not universally fund pre-K, charter schools can struggle to afford to offer pre-K if they don’t want to charge tuition. If they wanted to tap into limited state funding for pre-K, they would have to meet a separate set of quality standards, which can be a rigorous process. And there’s no guarantee that students will qualify for or receive one of the 4,000 need-based scholarships.

Still, it’s clear there’s a rising need for pre-K. Many traditional public school districts have started pre-K programs, drawing from their larger funding pools or charging tuition. In the last decade, the number of children in public school pre-K programs has doubled to about 20,000 students this year, according to state data. Some 460 schools offer pre-K, about 200 more than a decade ago.

For Sarah Lofton, principal of Avondale Meadows Academy, money is the high hurdle.

“I think we’d have plenty of interest,” she said. “Financing it is just the challenge.”

In a recent discussion about writing grants, Lofton was thinking about all the things she wanted for her school. “Sure, I would love a few more sets of Chromebooks,” she said, “but pre-K was the big-ticket item.”