Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s new evaluation law could mean more city teachers will earn a top rating, not fewer, city officials warned the state last month.

According to an analysis conducted by the city Department of Education, the state’s new evaluation system is “drastically more” skewed toward awarding teachers the top rating when compared to the system New York City has used for the past two years. In a 14-page letter sent to state education officials on April 27, Chancellor Carmen Fariña wrote that the “matrix” included in the law should be changed to correct the positive bias — one of a number of pointed recommendations offered by the city.

The letter, which the department kept under wraps for weeks, was sent as the state began the process of finalizing a new evaluation system for New York’s teachers and principals. Lengthy and detailed, it shows that city officials have been working behind the scenes to make the case for preserving much of the city’s current evaluation system while avoiding public criticism of the law as the city navigates a contentious legislative session.

The letter’s most surprising takeaway is that, in New York City, Cuomo may be about to exacerbate the problem he sought to fix through his new evaluation law. Cuomo complained for months leading up to this year’s state budget that the current evaluation system was flawed because it was too easy for teachers to receive a good rating. Last year, 9.2 percent of city teachers received the top rating of highly effective, compared to 58 percent of teachers outside of the city.

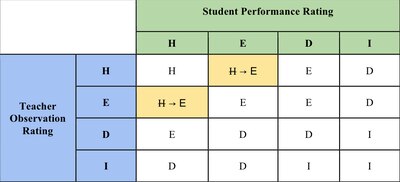

Under the new legislation, evaluations will be are based on two main components: student performance and classroom observations. Teachers can earn a highly effective rating by earning that rating on one component and an effective rating on the second. (Here’s how ratings from the two categories get combined into a single rating in the state’s new matrix.)

But Fariña argued that teachers should only be eligible for a highly effective rating if they earn that on both main components.

“This change would also eliminate the extremely strong bias toward highly effective that the currently specified matrix unintentionally introduces,” Fariña wrote.

Meanwhile, she said, the state should also take a hard look at the quality of the tests that will play such a significant role in the evaluations.

The city “does not feel confident that they fully capture student achievement growth,” Fariña said.

The State Education Department did not respond to questions about the city’s feedback, and the governor’s office declined to comment.

The letter is among dozens of documents and more than 3,000 emails sent to the State Education Department in the weeks after the legislature passed the controversial evaluation changes in April. After the law left many of the details of the new system to be decided by state officials, the education department requested feedback from districts, teachers, principals, parents, and other education groups about the design of the new evaluation system. That process culminated in a much-touted summit earlier this month, and most of the feedback was posted to the state’s website.

The city declined to share its recommendations, which were not posted online, though they were part of the public feedback process. A spokeswoman said the department was “entirely focused” on creating its evaluation system. State officials released the documents on Friday after requests from Chalkbeat.

On Monday, state officials are expected to unveil their own recommendations for the evaluation system, with final regulations to be approved no earlier than mid-June. Under the current law, districts have until Nov. 15 to implement their new evaluation systems, a timeline Fariña called “unrealistic and potentially detrimental” to a successful rollout of the new system.

The city is particularly concerned about the outside evaluators required by the new law, the letter shows. One way to comply with the regulation that every teacher be observed by someone who works outside of their building would be to hire least 320 full-time independent evaluators — an “extremely expensive” proposition given that the city already employs 900 operational and instructional support staff people.

To avoid that, the city is recommending that principals, assistant principals, and top-rated teachers be allowed to become certified evaluators for teachers at other schools, in addition to retired teachers, university faculty, superintendents, and superintendents’ staff members. The department is also asking for the state to allow the city to experiment with using outside evaluators for only a subset of teachers in the system’s first year.

The outside evaluation should count for between 5 and 20 percent of a teacher’s observation score, the city said, in line with the city teachers union’s suggestion that principals’ evaluations remain paramount.

The United Federation of Teachers, in its own advocacy letter, asked state officials to eliminate the “group measures” that allowed teachers of non-tested subjects like art to have their student performance scores calculated using students and subjects they didn’t teach. The city said that tactic should remain, along with another method that would restrict those calculations to a teacher’s own students, until more appropriate assessments became available.

Among the department’s other recommendations were to allow the use of student surveys as a “significant factor” in evaluations, something that would also require a law change. The city has piloted student surveys over the past two years, rolling them out in all schools this year.

Read the city’s entire letter below: