This is the second story in a three-part series about Brooklyn Generation School and New York City’s new school-turnaround program. Click here to read the rest of the series and meet the students of BGS.

The 10th-grade students at Brooklyn Generation School were still shuffling into their English class and pulling out copies of “Animal Farm” when Louise Bogue began asking them to recap the last chapter.

Her goal that Friday morning was to hurry students past that kind of simple recall. She wanted them to dig beneath the big plot point of the chapter — the power-hungry pig Napoleon running his rival off the farm — to unearth the author’s buried message. BGS has been trying to prod students to wrestle with complex ideas for some time, at least since a city evaluator a few years back said much of the school’s classroom activity was stuck at a low level.

That criticism would show up again this year, even after BGS had made it the focus of teacher trainings. Using sharp analysis to cut through thorny ideas has become increasingly important since New York adopted more demanding learning standards several years ago. But when evaluators told BGS teachers to push their students further, they never explained how to do that with teenagers who start so far behind, and with so many burdens weighing them down.

Just in Bogue’s class that day there was a boy who had to walk up to the board to read the notes, an 18-year-old repeating 10th grade for the third time. His teachers thought a psychological problem might be holding him back, but his foster parents had declined to send him to a psychologist for an evaluation. There was a girl resting her head on her purse who reads at an elementary-school level and had asked to be tested for a learning disability. Next to her was a boy who witnessed a family member’s murder and now occasionally erupted in rage. Months later, he would provoke a furniture-toppling fight during Bogue’s class.

Brooklyn Generation’s 50-percent graduation rate qualified it for the city’s new “School Renewal” program, which aimed to shift the city’s approach from sanctioning troubled schools to helping them meet such students’ needs. But while the program was starting to connect the school with more student services this spring, the city had yet to offer any training or coaching for its teachers. At the same time, the school’s principal was focused on a series of evaluations by the city and state that felt gravely serious, since both hold out closure as an option for floundering schools.

With its leadership distracted and the city slow to send help, Brooklyn Generation’s teachers were caught in the middle, ordered to improve but not always able.

Eventually, Bogue asked a boy from Haiti who is still learning English to explain why Napoleon seeks to control the other animals. He was stumped.

“It’s those why questions,” Bogue told the class, “that always get us.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio designed his $150 million Renewal program as a two-front rescue mission for struggling schools.

The first unit would rush in with mental health and social services for students so they’d be in better condition to learn. The other division — academic “SWAT teams,” as de Blasio memorably put it — would prop up the educators.

“We will begin mentoring principals and increasing professional development for teachers without delay, to improve instruction right away,” the mayor said in November. In a sharp pivot from the previous administration, de Blasio stressed that struggling educators should be retrained, not replaced.

At a press conference in March, he repeated that point, saying teachers “need constant training. They need to improve at all times.”

According to years of reviews, de Blasio’s diagnosis was just what BGS needed.

In 2012, just months after current principal Lydia Colón Bomani took over the school, a superintendent named Aimee Horowitz conducted an official audit of BGS. She found much to praise, but she also said that not all teachers were getting students to think at high levels and they weren’t using enough methods to gauge whether students made sense of the lessons.

A city review last year said teachers need to create classroom routines that lead to high-level thinking, and use the results from quizzes and other assessments to steer instruction. A state review this February said much the same. And a Renewal official who finally surveyed the school in April said she observed high-level questions in only about four of 10 classrooms, and teachers checking students’ understanding during three out of eight lessons.

Four years and two themes: teachers aren’t getting students to think deeply enough, and they aren’t keeping close enough tabs on students’ comprehension.

Horowitz is now the top superintendent overseeing the Renewal program. In an interview last week, she said there is still much to celebrate about BGS: the extra learning time, teachers’ collaborative planning, a “myriad of partnerships” with colleges and nonprofits, a respectful tone fostered by leaders who are “caring and supportive.” And yet, the central challenge of teaching quality remains, three years after Horowitz’s first evaluation of the school.

“I think the majority of the work,” she said, “is around improving teacher practice and holding teachers accountable for improving.”

At a series of press conferences in March, de Blasio trumpeted all the help the city was sending Renewal schools, especially around academics. Long-struggling Boys and Girls High School students got new Advanced Placement courses, Automotive High School teachers got “Renewal coaches,” and Richmond Hill High School teachers got training on ways to boost writing instruction. Other schools also received on-site teacher coaches, off-site teacher trainings, and frequent visits from Renewal officials since the fall.

“We are investing in tools that we know help students catch up and succeed,” de Blasio said in a press release that month. “More learning time, extra tutoring, coaches to help teachers improve instruction.”

The mayor seemed to be describing a different Renewal program from the one BGS knew.

It had received its first walkthrough from a Renewal team just days before de Blasio’s first press conference that month. The next month, one Renewal official would start visiting more often. Another official would connect Colón Bomani via email with the principal of a higher-performing school so they could discuss ways to boost attendance. (Renewal officials also offered her a coach, but she said she declined because she had already developed a productive relationship with a longtime coach.) She and other administrators would attend some workshops, including one about using data and another about a digital reading program. And the school hired a few professional artists this spring to work with students using a grant it successfully applied for from the city.

But there were no new advanced classes, no teacher coaches, and no BGS staffers invited to the writing and problem-solving workshops that other Renewal high school teachers attended. BGS teachers’ main interaction with the program that month was answering survey questions by researchers the city hired to analyze the Renewal schools.

Five months after Renewal launched, BGS staffers wondered what it would require of the school, what help the school would get, and what would happen if it didn’t meet those still-unknown targets.

“I don’t know a lot,” 10th-grade science teacher Kaylan Buendia said in March, “other than, it means we’re going to be evaluated and offered support.”

Colón Bomani knew only slightly more about Renewal. And though its purpose was to uplift floundering schools, she still had concerns.

Before taking over BGS four years ago, she was assistant principal of a high school for students who had fallen behind in other schools. When she left, she took with her the idea that students’ classroom struggles often stem from personal ones, which schools must address if they want those students to learn. To her, the student-support half of the Renewal program made perfect sense.

“It’s the right answer,” she said, adding that she thinks Horowitz, who as superintendent oversaw Colón Bomani’s previous school, is the ideal leader for the effort. “I’m sold.”

But she and other staffers worried that the program could stigmatize the school, weakening morale and driving potential teachers and students away. She also fretted about hitting Renewal’s targets while also acting on the state’s feedback and meeting the requirements of the major “community school” grant the school received to hire the artists and add other services. And if the school stumbled and didn’t make quick gains, Renewal still posed the threat of closure.

What’s more, despite the school’s 50-percent graduation rate and long-documented struggles with instruction, she wasn’t sure she wanted whatever academic help Renewal might offer. She argued that the school had been steadily improving and worried the program might force it to adopt teaching practices and materials or make other changes that weren’t a good fit with the school’s longer year and college-focused approach.

“Nobody’s averse to having people come in and help us — we have challenges,” Colón Bomani said. Her problem was with the idea that “you’re a consistently low-performing school … now here are all the remedies, without consideration of where we came from.”

Officials were still analyzing Brooklyn Generation, so Colón Bomani hadn’t been told exactly what to expect from Renewal. She could only guess.

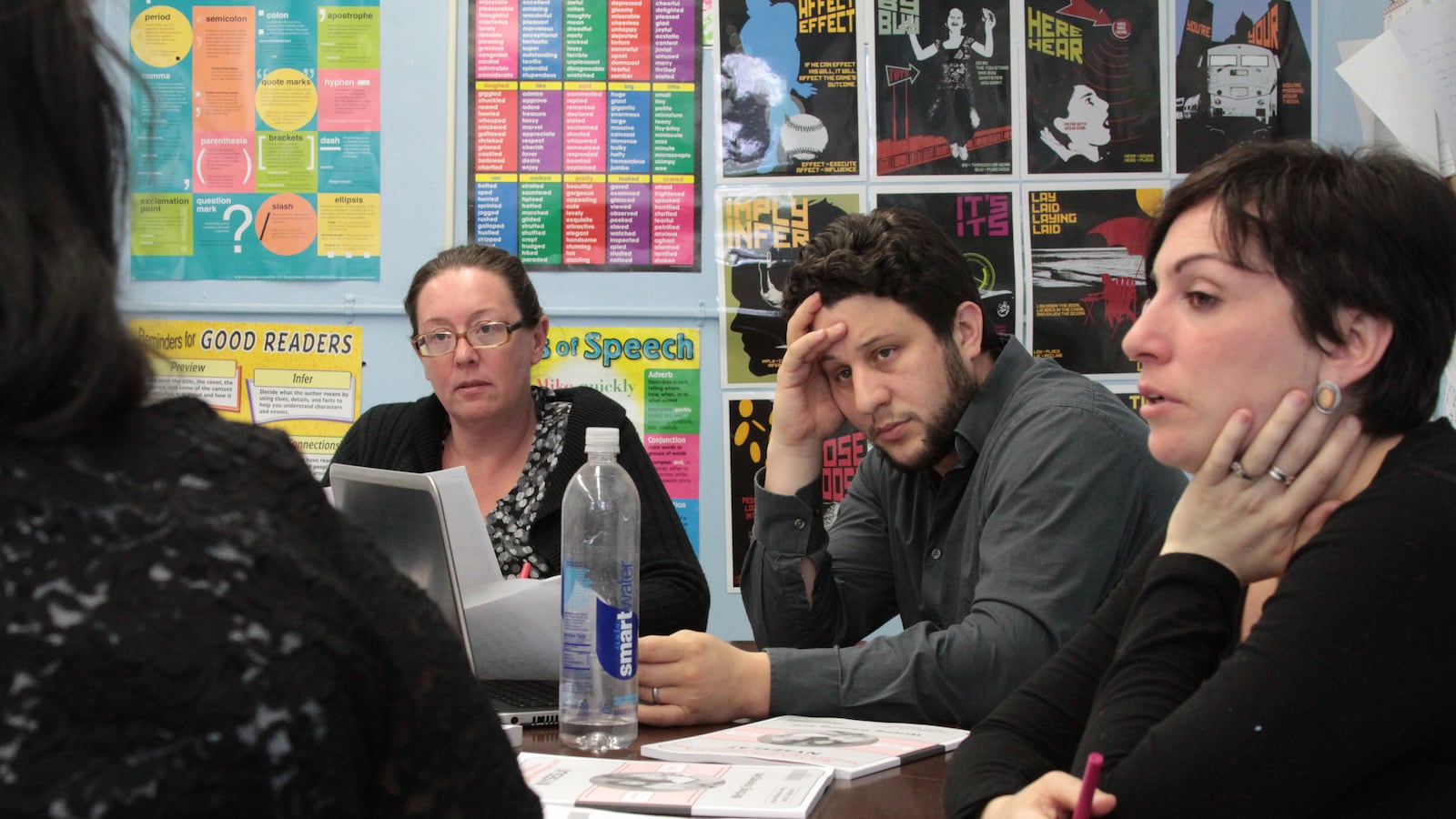

After classes ended one March afternoon, Brooklyn Generation’s science and math teachers scurried into a ninth-grade classroom for their weekly meeting. A teacher poked her head out of the door to chide some freshmen sprinting down the hallway, then sat down. The teachers had come to get better.

Under Colón Bomani, BGS teachers have often tried to make changes based on the feedback they have received. But juggling the city’s demands, students’ needs, and the school leadership’s shifting priorities, the school has struggled to pull off that self-improvement.

To boost the level of classroom questions, teachers had started using a planning tool to help them formulate rigorous queries ahead of time, and students were taught to distinguish between simple and sophisticated questions. This year, the school tried to strengthen students’ analytical thinking by having them write in journals and engage in structured discussions known as “Socratic seminars.” (After that lesson about the power-hungry pig, Bogue planned a seminar around the question, “Is corruption inevitable?”)

But some of those initiatives fizzled out. For example, the Renewal official found only two teachers who were still talking to students about the different levels of questions, and just three of the 11 lesson plans she collected used the question-formulating tool. Teachers said the administration devoted many staff meetings this year to preparing for the state reviews, when they could have been used to sustain the school’s own initiatives.

"When I’m stressed out, I have less patience with the kids. And these kids need a lot of patience and a lot of love."

Jacline Bantegui, ninth-grade science teacher

They also pointed out the limited resources the school has to serve its needy students. For example, staffers say the school requires about five special education-certified teachers to work with its students who have special needs, yet the school has just three of those teachers. (The school lost $256,000 in 2013 when the city changed the way it funds special education.) Considering those challenges, teachers say, it’s hard enough to stay afloat, much less keep getting better.

“It’s constant triage,” said Adam Hixon, who teaches one of BGS’s college and career-focused courses. “Some things end up getting cut at some point.”

On this Wednesday afternoon, though, the teachers were trying to follow the state’s recommendations.

Based on a finding from a February audit, Colón Bomani had asked the teachers to choose one skill to assess students on at the start of a unit of lessons, three times during it, and at the end. The idea was to get into the habit of regularly assessing students, while also collecting evidence to show the state.

Neil Garguilo, the 10th-grade algebra and trigonometry teacher and a schoolwide math-team leader, explained that to the seven other teachers in the room. But they had questions: What counts as a mid-unit assessment? Must those be graded? And isn’t it overkill to document the kind of routine checks — calling on students or glancing at their work — that teachers already do multiple times each lesson?

“It’s a show, everyone acknowledges that it’s a show,” Garguilo replied, validating his colleagues’ frustration with all the extra oversight, but also subtly pushing them to keep improving their practice. “But, you know, I personally wouldn’t do anything if I didn’t consider it helpful.”

A few minutes later, Colón Bomani popped into the room and launched into a 37-minute talk about assessments. Her dream, she said, is for students to constantly monitor their own understanding, instead of waiting until the next quiz.

After she left, the teachers started to pack up. They did not seem much closer to enacting the state’s recommendation, or even clear on what they were told to do.

“We should assess each other,” a teacher in a gray sweater said to a colleague, “on what she just said.”

If the pressure to keep doing more and better exasperated some teachers at Brooklyn Generation, it invigorated two of its sophomores, the twin sisters Elodie and Ismaelle Oriental.

They experience the world as one great competition. Their mother, Marjorie, one of 16 children who on her own moved from Haiti to the U.S. as a teenager, had told them that everyone had an equal shot in America. What separated the victors from the rest was effort and education. To illustrate this, Marjorie explained to her daughters how she couldn’t obtain a license to open her own beauty shop because she lacked a diploma.

“Mom would ask,” Iszzy said, “do you want to be in that situation?”

When Marjorie suddenly fell ill last year, she ordered the girls not to slack on their schoolwork. So on days when they would rush to the hospital after school and stay until midnight or later, they still turned in their homework the next day. At the start of the school year, Marjorie died. That seemed only to intensify the twins’ drive to live out her advice.

When they returned to school, their only request was that their teachers give them as much work as their classmates. Every afternoon after class they traveled to a college campus: Brooklyn College for a college-readiness course, Medgar Evers for an aquatic science program, SUNY Downstate Medical Center for college-level anatomy and physiology lessons, and Columbia University for business-themed mentoring. Yet another program took them on science-related excursions each Saturday. After that came several hours of homework — perfectionists, they would sometimes rise at 2 a.m. and work until school started.

All of those opportunities flowed through BGS and, specifically, Michele Hill, the school’s college and career director. She set the twins up with all their extracurricular activities, but also looked after their personal lives. She had pushed them to eat better and try yoga, and made sure they were adjusting to moving back in with their father, whom they had not lived with since he and their mother separated when they were small children. While she was proud of their accomplishments, she also worried that they had left themselves little time to process the loss of their mother.

But, as Elodie put it, “Life goes on. Your grades are not going to wait for you to grieve.”

The twins were still at school one late March afternoon as the daylight faded outside.

Parent-teacher conferences were that night, so while the twins waited for their father to arrive, they worked on a project they would present at a statewide science fair that weekend in upstate New York. (During the trip, they would stay in their hotel room rehearsing their presentation one night while their classmates sang karaoke.)

When their father arrived, the four 10th-grade teachers showed the twins their averages for the second trimester: 99.4 percent for Iszzy, and 99.5 for Elodie. The two screamed in excitement. Louise Bogue, the English teacher, praised their work ethic and the way they inspire their classmates to try harder. But the teachers also said they worried about the hours the girls keep and the pressure they feel to excel.

“That stress level that you’re putting on yourself to get those grades, that’s what you need to work on for trimester three,” Bogue said, suggesting that they set time limits for homework, a skill they would need for college. Their father, Joseph, nodded.

What wasn’t clear that day was whether the girls’ perch near the top of their class at BGS would put them within reach of their goal of attending an elite university. When Colón Bomani pushed her teachers to up their game, it was because she sometimes questioned how students like the twins would compete with peers at the city’s best public schools.

“They’re the cream of the crop here,” she said one afternoon, “but drop them into Stuyvesant, drop them into Brooklyn Tech, where do they fall?”

By April, Brooklyn Generation was preparing for its own kind of report card.

Under former Mayor Bloomberg, schools received annual letter grades based on metrics like test scores and graduation rates — a tactic he also used with restaurants, which critics saw as a way to shame struggling schools to improve. De Blasio ditched those grades, but kept part of Bloomberg’s accountability regime: “quality reviews” conducted by city evaluators who observe lessons and interview staffers in order to size up a school’s teaching, leadership, and culture.

With those reviews, the oversight of newly empowered superintendents, and the threat of staff changes or closure, de Blasio’s approach to struggling schools is meant to fuse support with accountability. He hardly had a choice: Federal law and the state education department require districts to intervene at schools with chronically poor test scores and graduation rates. And critics who said de Blasio intended to “love the city’s notorious failure factories until they got better” would surely pounce on a plan that didn’t hold schools accountable for results.

By this spring, people at BGS didn’t feel much more supported, but they did feel the pressure to show results. That was especially true for the quality review, which was scheduled for the last week of April. The findings would be used to shape the school’s improvement plan. A positive review, Colón Bomani hoped, might help spring the school from the Renewal program, with its stigma and specter of closure, altogether. They were determined to get top ratings.

In the weeks leading up to the review, similar to what happened before the state visit in February, “QR” preparation consumed the school. The administration conducted a mock review and discussed the actual one at staff meetings. Teachers spent hours assembling review binders with lesson plans and student work; some showed up at the school over spring break to make sure their classroom bulletin boards met the administration’s standards.

Though de Blasio had insisted his officials would tour troubled schools to learn what help they needed, people at the schools still saw the reviews as exams where they had to prove they had learned from past feedback. To them, the classroom displays and binders represented opportunities to make sure the reviewers saw what they were looking for.

“When we’re being observed,” Bogue said, “we have to make things painfully obvious.”

One sunny afternoon a few weeks before the review, the 10th-grade teachers gathered for their weekly “kid talk” meeting to troubleshoot student issues with a social worker. As soon as the social worker left, talk turned to the quality review.

The administration said every teacher’s binder must have two pieces of evidence for each of the metrics the evaluator would assess. They should use clipboards to document when they check students’ understanding during class, and those bulletin boards must be up to snuff.

"Nobody’s averse to having people come in and help us — we have challenges."

Lydia Colón Bomani, principal

“Bulletin boards and clipboards,” Garguilo said dryly to his colleagues, “the keys to being a great teacher.”

Like a student cramming for a final, the administration at times seemed more worried about their grades than the official purpose of the reviews, which is to guide the school’s growth. That fixation was taking a toll on teachers.

One teacher said she received less feedback about her lessons this year; others complained about getting less backup on student discipline. Another said the review preparation sidetracked other school efforts, including the Socratic seminars and journal writing. Other teachers said it distracted from curriculum planning and snatched up training time that could have been spent on meatier topics, like how to accommodate all the students with special needs in general-education classes.

“That would help me to be more successful,” said Andrew Annunziata, the 10th-grade history teacher. “But so much of our time and energy goes into getting a haircut for the city.”

The extra work mixed with the pressure of the reviews and the shadow of sanctions to create a toxic brew of stress. Teachers started asking whether it was worth working at a Renewal school, and talk of higher-than-ever turnover after this year rumbled through the halls. Some teachers worried about how all the strain was affecting students.

“When I’m stressed out, I have less patience with the kids. And these kids need a lot of patience and a lot of love,” said ninth-grade science teacher Jacline Bantegui. The pressure of the reviews, she said, “made me a worse teacher.”

The day before the quality review, Colón Bomani called the staff into a classroom after school. She reminded them why they had been working so hard to earn “well developed,” the review’s top rating.

“In my head, one of the ways we get off the Renewal list is to do nothing less than well developed,” she said. “I realize it’s been anxiety-provoking.”

That went for her as well as her staff. Before the state review, she and her assistant principal, Louis Garcia, had to complete a 32-page self-assessment and gather a host of documents, from suspension records to classroom observation feedback, teacher-training plans, and letters to parents. For the city review, they wrote up a separate 15-page self-assessment.

At the meeting, she called out her favorite bulletin board (it featured students’ assessments of their peers’ work, a classroom practice the school had been working on), and emphasized that lessons should be short on lectures and long on group work. She said she and Garcia would give them all feedback that afternoon from the mock review, where they observed lessons and inspected bulletin boards.

She ended the meeting by reading from the prologue to “Teach Like Your Hair’s on Fire,” a book about the methods of a zealous fifth-grade teacher. While she read, a teacher in the back of the room fine-tuned a presentation on his laptop for the next day’s lesson.

For the administration and the teachers, just like Iszzy and Elodie, there was no doubt they were working hard — maybe harder than ever before. What wasn’t obvious was whether it was the right work to set the school on an upward course. And, if not, whether the city would steer it in the right direction.

Colón Bomani finished reading and said, “So go teach like your hair’s on fire.” Then she added, “Well developed.”

As the teachers filed out, she stayed at the desk up front, her head resting in her hands.

Support for this series was provided by The Equity Reporting Project: Restoring the Promise of Education, which was developed by Renaissance Journalism with funding from the Ford Foundation.