An idea to merge two elementary schools in Manhattan’s East Village seemed to make perfect sense for a district that’s been home to a grassroots push for more diverse schools.

District 1’s East Village Community School is overcrowded, and full of mostly white and middle-class students. A block away, P.S. 34, which runs through middle school, has room to spare, and enrolls almost exclusively black and Hispanic students who live in the surrounding public housing.

But a preliminary proposal to combine the two campuses was tabled last week, after meeting stiff resistance from families at P.S. 34, who said a merger was tantamount to closing their school.

“Why do you want to come take this?” asked Shamear Gainey, whose daughters attend P.S. 34, about the initial proposal. “Go somewhere else.”

The pushback is another reminder of how difficult it can be to integrate New York City schools, which are among the most segregated in the country, and the toll that such efforts often take on communities of color.

It is notable for another reason: The education department — which has been persistently criticized for ignoring the voices of parents — heeded the concerns of families early in the process by pulling the proposal before it even formally came before the community rather than plowing ahead.

“We wanted to make sure that, whatever the idea was, that we did it with the community, not to the community,” said Carry Chan, superintendent of District 1, which also includes the Lower East Side and part of Chinatown.

Education department officials in recent years have relied on school consolidations, rather than closures, to address enrollment issues across the city. For school communities, however, it can feel like a distinction without a difference, especially when schools have their own long-standing approaches to teaching and learning that can be hard to blend into one.

At progressive East Village Community, parents are welcomed for guitar sing-alongs, and play is a central part of learning. At P.S. 34, the school’s website describes a focus on building perseverance through difficulties, and college and career readiness.

If the city moved forward with combining the two, parents at P.S. 34 worried about losing their school name, their culture, and even their middle school — which parents had previously fought to get.

Parents said P.S. 34 needed more resources to serve its own students well, not to be subsumed to make room for a better-resourced school.

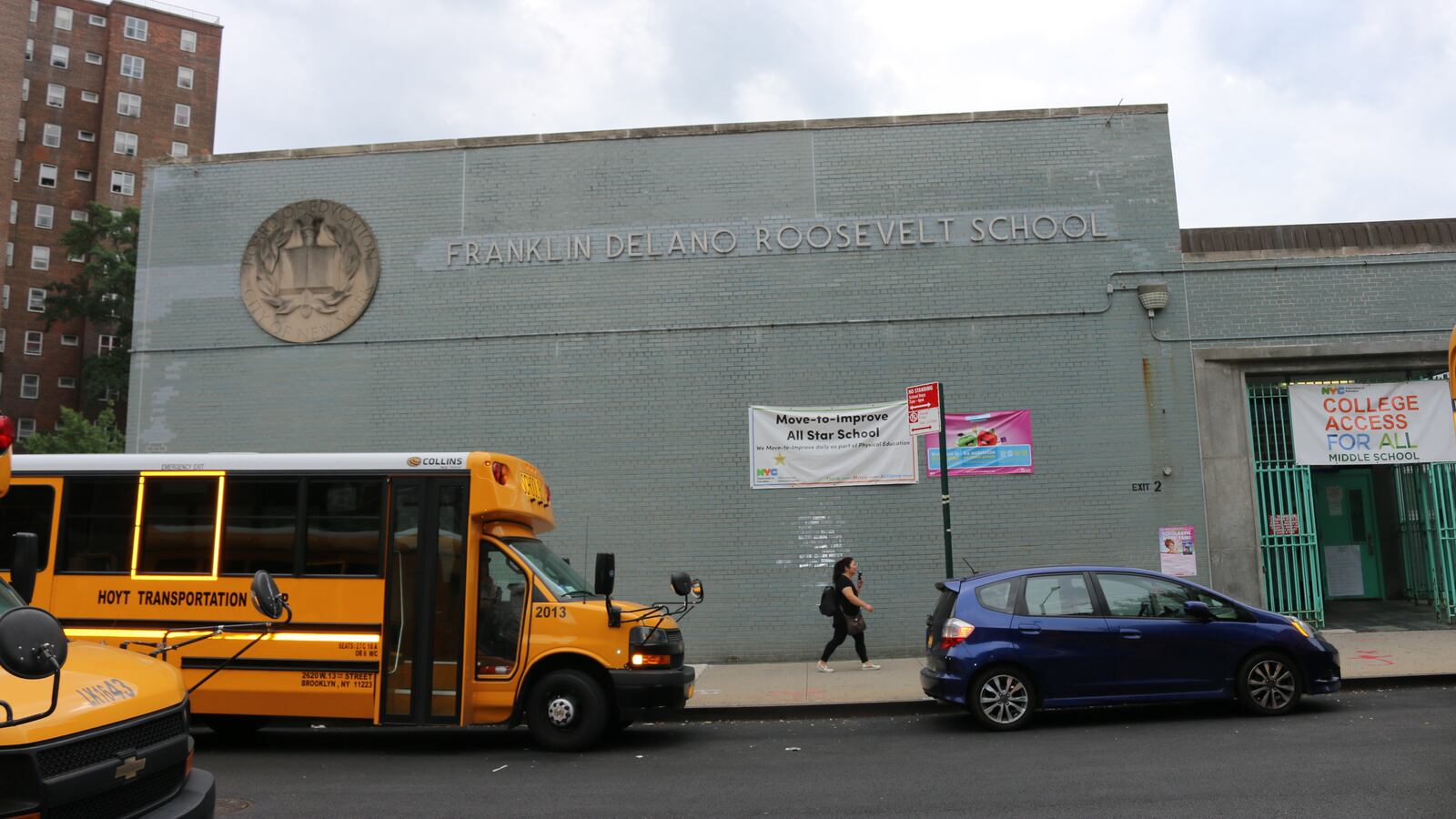

Bounded by public housing and industrial buildings, P.S. 34 has the highest poverty rate of any school in the district: 99% of students come from low-income families. Just over a quarter of students passed their state English exams last year, and only 15 percent scored on grade-level for math.

Though white, middle-class families have largely steered clear of P.S. 34, they have flocked to East Village Community. Its building, shared with two other schools, is over 130% capacity. More than 57% of students there are white, versus the district average of 18%. Students there outperform the district average on both English and math exams.

In 2017, District 1 took steps to break up these extreme concentrations of students, winning approval for the city’s first districtwide integration plan that gives admissions priority to certain students. Unlike most other parts of the city, District 1 parents apply to elementary schools through lottery-based admissions. But even with the admissions priority, unless application patterns change dramatically, neither will student demographics. That’s a tall order when, research shows, parents consider test scores and racial composition of a school when weighing their options.

With the merger off the table, the original challenges still remain: East Village Community needs more space, and the district still wants to integrate its schools.

“Our reality of being cramped in an overcrowded building has not changed, but a new light has been shined on the inequity and segregation that exists in our small district,” East Village Community’s principal Bradley Goodman wrote in an email to his school’s parents. “I hope that we will continue to engage in this critical, albeit sometimes difficult and uncomfortable conversation.”

Patricia Marrero, who has two sons at P.S. 34, said integration is a worthy goal. But making that a reality will first require trust built across communities that have rarely had a reason or chance to interact, she said.

Efforts to change that are already starting in small ways: Marrero said East Village Community parents have invited the P.S. 34 community to come to their Halloween party.

“Communities need to be brought together,” Marrero said. “This is a start.”