When the pandemic gripped New York City in March 2020, high school sophomores had no idea that their remaining two years would look nothing like they had imagined.

Many of those sophomores are graduating now, having navigated school closures and two unusual years marked with grief and isolation. City officials celebrated the full reopening of public schools last fall, but the year was not nearly as normal as anyone had hoped.

“It’s been weird because I don’t really feel like part of the school — like, I kinda had to remember where everything was again as a senior,” said 18-year-old Alexandra Cruz, who graduated this month from Millennium Brooklyn High School. “I think it would have felt like more of a community if I had been there for the full four years.”

Like students in other grades, some seniors worried about contracting COVID and infecting high-risk relatives at home, especially as a winter surge emptied schools for weeks in December and January. But on top of the anxiety of being around peers for the first time since the pandemic hit, seniors also had to decide on what came after high school.

For many others in the Class of 2022, returning to the building was a boon. It meant seeing their friends and teachers again and learning in a classroom instead of through a screen. And for some, it was why they made it to graduation.

We spoke to four high school seniors who graduated this month about their experiences and what they plan to do next.

ZHENGHAO LIN, 18, FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT HIGH SCHOOL, BROOKLYN

Zhenghao Lin felt overwhelmed the moment he stepped into the crowded hallways of his school in September, his first time back since March 2020.

Fearing he would contract COVID, Zhenghao, one of about 3,000 students, wore a face shield over his mask. He was afraid to touch door handles or stand too close when talking with others. He worried his peers would judge him for feeling nervous. He feared he might be subjected to racist bullying as he had in the past, because of rising anti-Asian hate crimes.

“I was not really able to, like, learn things that first few months because I felt constantly distracted,” said Zhenghao, who was diagnosed with anxiety disorder in 2020.

The pace of instruction also frustrated him because it felt slower than his virtual classes from the previous year. Students rarely asked questions during virtual learning, but they frequently raised their hands in person.

School staffers often stopped him in the hallway to ask how he was. He would say he’s not OK.

They would refer him to a counselor, who typically had a packed schedule. Zhenghao, however, was already seeing a therapist in private practice. Those twice weekly sessions helped him turn a corner in March, when the city dropped the school mask mandate.

Zhenghao continued wearing his mask, but he found that seeing his classmates’ faces and working with them in groups helped him connect with them and read their facial expressions, which were friendlier than he’d expected. To his surprise, he didn’t experience any racist bullying or comments, which he credited to advocacy campaigns across the city raising awareness about anti-Asian hate crimes.

Through therapy, he began to understand that he was at low risk of becoming severely ill from COVID, having been fully vaccinated without any high-risk conditions.

Zhenghao stopped striving for 100’s in every class, he said, and allowed himself to miss some assignments. He also dropped his AP Chinese and physics classes. He didn’t need them to graduate, and he found them too stressful and difficult.

As Zhenghao gets ready to attend a small liberal arts college in Vermont in the fall, he already has an idea for his future career: He’s planning to become a therapist.

KEKELI AMEKUDZI, 18, BROOKLYN TECH HIGH SCHOOL

Kekeli Amekudzi missed 30 days of school this year.

Most of those days she was taking care of her mother, who was diagnosed with cancer before Kekeli’s freshman year and took a turn for the worse last year.

“There’s just, like, so many responsibilities that I have to take care of,” Kekeli said.

The city considers Kekeli someone who was “chronically absent,” for missing at least 10% of school days. More than a third of students citywide were on track to have missed at least a month of school this year.

During remote learning, Kekeli could help her mother get to doctor’s appointments and work on schoolwork from the waiting room. She had more time to cook and clean.

Returning to school this year meant Kekeli could see her friends more regularly, but it was challenging to balance in-person learning with responsibilities at home. Being inside the 6,000-student high school, the nation’s largest, also brought concerns about reinfecting her mother, who’d already had COVID while in the hospital.

Kekeli’s teachers met with her to catch her up on assignments, and some deadlines were extended. She found it helpful to vent to a teacher during office hours about the stress of school or her mom’s illness.

A sense of normalcy continued to feel out of grasp.

COVID cases began rising in December and exploded in January with the omicron surge, causing stress and absences among students and teachers, prompting students to organize a walkout at Brooklyn Tech. Less than three-quarters of students were at Brooklyn Tech on the Friday after winter break ended, according to data compiled by PRESS NYC, a group advocating for stronger COVID protections in school.

Her extracurricular activities, such as the debate team, remained virtual. Field trips for her favorite environmental science courses were paused until the spring.

Kekeli received some help while applying to college, but she had to navigate some details on her own, such as figuring out what financial forms she needed.

She is planning to attend Emory University in Georgia, where she wants to major in environmental science and international law. She’s considering a gap semester to help her mother transition to a home health aide.

She feels that she and her peers made it through one of the hardest times in New York City’s history. She has tried to take action, participating in climate marches, protests over gun violence, and abortion rights — making friends along the way.

But Kekeli is still grappling with a sense of loss that many graduating seniors feel.

“When we came in freshman year, we came in with so many expectations with, like, what our final year would be, and so many events were getting canceled or postponed or just weren’t done because of COVID,” Kekeli said. “There’s just been this sense of like, where did it all go?”

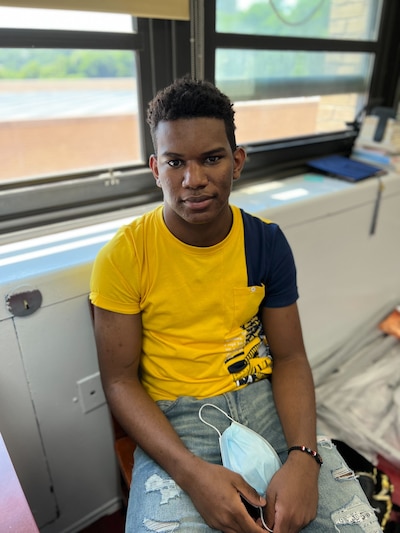

ABRAHAN CASTRO GERMAN, 19, ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS AND INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT PREPARATORY ACADEMY, THE BRONX

Abrahan Castro German spent the previous school year mourning the loss of a beloved uncle, who died of COVID in his home country, the Dominican Republic.

Abrahan, who immigrated to the Bronx in February 2019 and is learning English, navigated that grief alongside remote school, which he described as “very difficult” because it was hard to get extra help from teachers.

So he felt both happy and nervous to be returning this past fall to his Bronx high school, ELLIS Prep, which serves under-credited, over-age students who are new to the United States.

But halfway through this school year, he suffered a new blow. On New Year’s Day, Abrahan’s older brother died in a motorcycle accident back home.

School staff and his friends noticed that the normally bubbly, well-liked teen — known by one counselor as “The Mayor” — was quiet. Sometimes he asked to leave for the day, but staff wouldn’t let him, he said. He stopped doing much of his homework.

He missed his mother and grandmother, who are in the Dominican Republic, and would stay up at night looking at photos of his brother and uncle on his cell phone.

“I’m thinking about what feeling my brother went through in the accident, what feeling my mother went through when she lose my brother,” Abrahan said.

Teachers and guidance counselors saw his grades dipping in every subject and urged him to keep up. They worried he was falling off track to graduate.

He visited guidance counselors daily explaining how he was physically in the classroom, but his mind was on his family.

At one point, a counselor told Abrahan that his brother would have wanted him to graduate. He said he wanted to give up, but the counselor replied, “You need to try, and you can.”

Abrahan said he began feeling like himself again around March. He credited ELLIS staff and his friends for helping him work through his grief, as well as family back home who encouraged him to stay on track. He began catching up on school work. He decided that he needed “to wake up” and think about his future.

As the school year wrapped up, Abrahan was still seeing his counselors every day. Pulling a C-average, he was accepted to Guttman Community College in Manhattan. Abrahan plans to take a course over the summer to improve his English, according to a counselor.

Abrahan said he’s nervous about Guttman, especially seeing new students and new teachers, and leaving his ELLIS family behind.

But he feels driven to stay on track and “try – for my future, for my brother’s son, for my mom.”

ALEXANDRA CRUZ, 18, MILLENNIUM BROOKLYN HIGH SCHOOL

A year and a half of remote learning was bad for Alexandra Cruz’s mental health. But returning to school full time proved to be just as difficult.

Alexandra, who said she has severe social anxiety, was nervous to see hundreds of other students again, at a school where just 17% of students are Hispanic like her.

While the year started off OK, it took a turn during the winter’s omicron surge. Many peers were out sick. On the Monday before winter break, just under half of the school’s students came to school, according to data compiled by PRESS NYC. Alexandra stayed home that week as a precaution.

She struggled to make up a week’s worth of old assignments and keep up with new ones.

Her grades were slipping, and she was pulling all-nighters to keep up with what felt like mounds of homework, longing for the flexibility and leniency of remote learning. It was also tough to stay engaged in class while her friends were out sick.

“It was just so hard for me — I just didn’t have anyone to talk to,” she said.

She felt teachers weren’t checking in enough to find out why students were struggling to keep up. Seventy-three percent of the school’s teaching staff is white, Alexandra pointed out, which also felt alienating. Sometimes, she just wanted “a nice Hispanic woman” as a teacher who could relate to her.

Alexandra found some solace in her weekly meetings with a school guidance counselor, where she could drop in and “vent” if she felt too overwhelmed during class.

She began worrying about college in April while also studying for her AP exams. She’d narrowed down her choices to SUNY Oneonta and Clark University in Massachusetts, but COVID rules prevented visitors from seeing the dorms at Clark, so she couldn’t “get the full picture.”

By May, when school calmed down, she had come to a realization after months of dealing with her social anxiety: It’s OK that she’s not friends with many of her classmates.

“I feel like a weight has been lifted off,” Alexandra said. “All these people in my class — I can’t connect with these people. I already have my friends. I’m just sort of looking forward to the future.”

Alexandra decided on Clark University. She chose a school outside of the city in order to get a fresh start somewhere new.

“I’m going to try to join clubs with people of color so I can talk to people who I can connect with,” Alexandra said. “It makes me nervous, obviously, but I’m excited.”

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.

Having trouble viewing this form? Go here.