Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

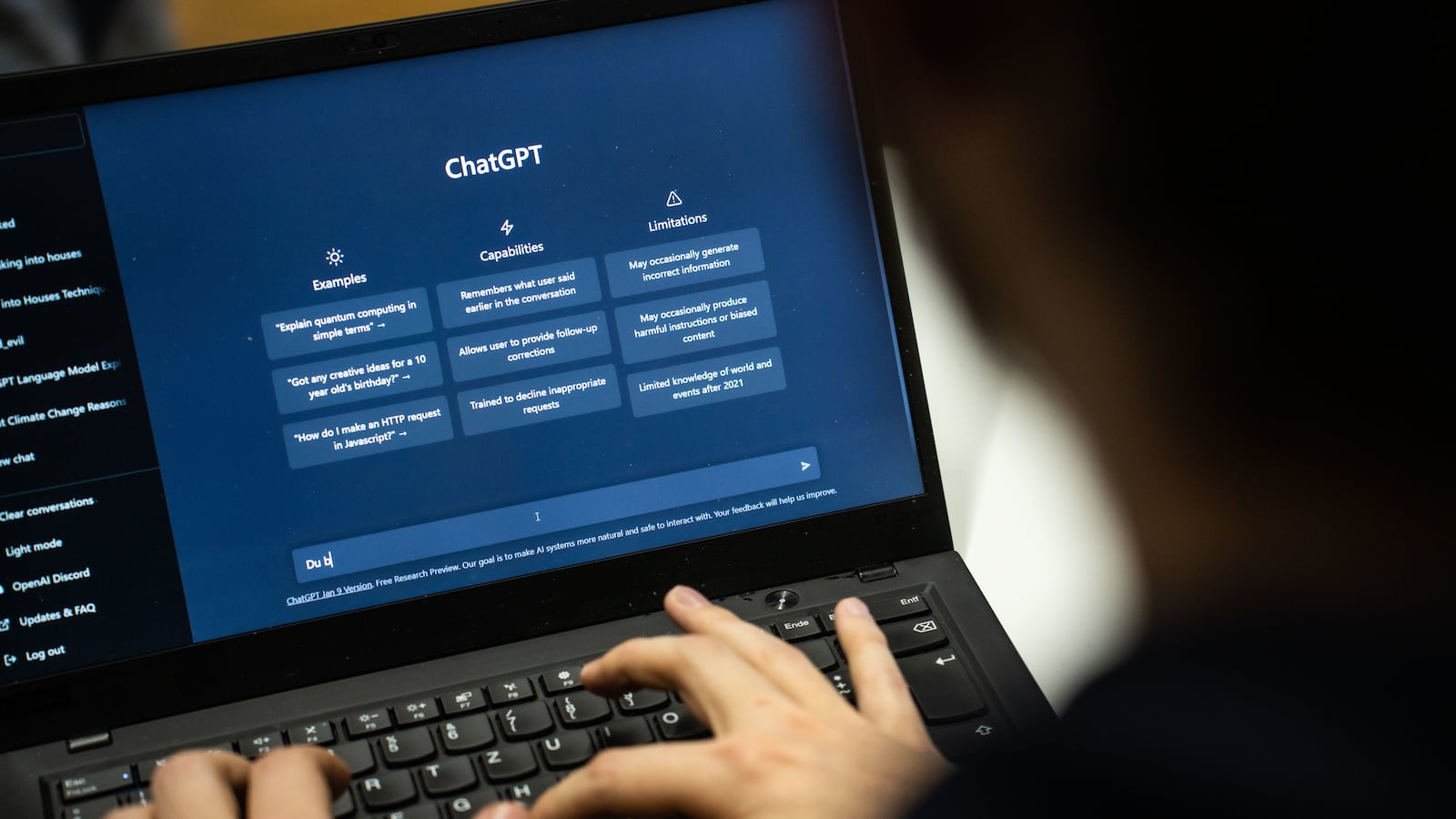

Kangxi Yang, a junior at Staten Island Technical High School, was surprised last year when her Advanced Placement Computer Science teacher encouraged her to use ChatGPT — an artificial intelligence-powered chatbot that some educators fear offers students a powerful agent for cheating and plagiarism.

Her school had warned students against relying on ChatGPT and other AI tools to complete their writing assignments, but Yang’s teacher showed them how to use the chatbot to debug their code, allowing them to quickly diagnose and correct their errors.

“You can ask the AI tool to explain what is wrong with your code, so that you’re also learning from it,” she said. “It was a really good tool for that class.”

New York City school officials have grappled this year with how to respond to the new technology, and ensure that it does less harm than good.

In January, New York City schools blocked ChatGPT on school devices and networks, citing “negative impacts on student learning, and concerns regarding the safety and accuracy of content.” But a few months later, the city reversed course, with schools Chancellor David Banks proclaiming the city’s schools were “determined to embrace its potential.”

Today, just over a year after the tech group OpenAI introduced ChatGPT to the public, some students at New York City high schools report widespread use of AI-powered chatbots among their peers. The same patterns appear elsewhere, too: In one national survey from July, 44% of teenagers said they were likely to use AI-powered tools to complete their schoolwork for them, even though a majority considered it cheating.

While some in the city have used the tools as tutors to help break down difficult concepts and work through challenging assignments, others have looked to them as a shortcut for easy answers. And though some tutoring companies have seized on the opportunities afforded by AI, experts warn the virtual tools can at times provide incorrect information or perpetuate societal biases.

Here’s how four high school students say AI-powered tools have changed the way students engage with their schoolwork:

An added resource at home

At Staten Island Tech, Yang hasn’t encountered many teachers who are strictly against using AI-powered tools.

Earlier this year, when her English class read “The Scarlet Letter,” a novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne, students were assigned a group project analyzing the book. Part of the assignment included designing a letter “A,” which the main character of the novel is forced to wear on her clothes.

For groups who weren’t confident in their artistic abilities, Yang’s teacher noted students could use images generated by AI based on their prompts.

Yang hasn’t personally seen many students at her school use AI tools to cheat on assignments, though one of her peers did submit an AI-generated application to her underwater-robotics team.

At home, Yang has used Bard, an AI-powered chatbot developed by Google specifically as a learning tool for teenagers, to gain new insights into her coursework. It includes safety features aimed at preventing access to unsafe content for younger users.

“For A.P. U.S. History, I have to do daily textbook readings, and a lot of the concepts I’m not sure about,” Yang said. “I search up certain terms to help me understand what they mean, or just to help me understand the materials better.”

AI tools have been a useful resource at home, Yang said, but they shouldn’t become more prevalent in the classroom.

“There’s a reason why a teacher is right in front of you,” she said.

AI spotlights anxieties about grades

Emily Munoz, a senior at Truman High School in the Bronx, said that at her school, fear hangs over the discussion of AI-powered tools. (Munoz is currently a Student Voices fellow at Chalkbeat).

“People are scared to talk about it,” she said. “Even teachers, they’ll get AI checkers to see if you’re using it in your essays.”

Those checkers are “not always accurate,” she said.

Munoz said she understands why her teachers are concerned. Some students at her school have looked at ChatGPT and other tools as an easy way to get their essays written quickly — a use that diminishes originality and harms their ability to learn, Munoz said.

At the same time, she worries some students have been falsely accused of using AI tools.

The problem stems not from the ease of access to the tools, but from the extreme focus on grades and academic success, Munoz said. If her peers didn’t feel so much pressure to score well on assignments and instead emphasized simply learning, they might be less likely to turn to tools like ChatGPT, she added.

“Even before AI, people would sometimes take other people’s essays,” Munoz said. “Or people would just search online, and they’d find something there and take it.

“AI is just bringing these issues to the table,” she said.

Ease of AI shows need for curriculum change

Benjamin Weiss, a junior at Midwood High School in Brooklyn, said that he’s “very annoyed” with the way students are taught, and that student use of AI shows what’s wrong with the curriculum.

The emphasis on standardized testing at his school has meant a lot of assignments are geared toward exam preparation — work that Weiss said can be easily solved by AI-powered chatbots.

“All of it is kind of like: We read the textbook, we memorize the textbook, we answer test questions,” he said.

Some history assignments, for example, have asked him to regurgitate facts without calling for his own interpretation and analysis, he added. While many of his peers have welcomed the use of the tools, Weiss believes they spotlight inherent flaws in the educational system.

If more of his schoolwork involved project-based learning and assignments that helped foster critical thinking, Weiss said, students would be less inclined to use AI.

“For the most part, it’s really a convenience thing,” he said. “It’s just so easy to use these tools.”

Peers have gloated that using ChatGPT on homework means they “can work smarter, not harder,” according to Weiss.

Some teachers have been open to students using AI-powered tools in a limited capacity, but others have adopted a zero-tolerance policy toward them, Weiss said. From speaking to administrators, he knows his school is considering how the tools can be further incorporated into classrooms, and how it can better adapt to the new technology.

Weiss hopes AI will spur an open dialogue at schools across the city.

“This is just a great time to revisit the conversation about how we want to teach students,” he said. “What’s the optimal solution for students and also for teachers who don’t want to punish students and who want to teach with more creativity?”

AI poses ethical questions in class

At United Nations International School, a private school in Manhattan, 11th grader Enkhdari Gereltogtokh has had to contend with the ethics of artificial intelligence in several ways.

In her English class this year, Gereltogtokh read “Klara and the Sun,” a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro that is narrated by a robot developed to serve as an “artificial friend” to a teenage girl.

“It’s very interesting in how it thinks about the juxtapositions of artificial versus natural,” she said of the book.

That theme has persisted in her own interactions with AI-powered tools. When her English teacher encouraged students to see how ChatGPT’s literary analysis compared with their own, Gereltogtokh noticed clear distinctions between how humans and AI understand writing.

She asked it to analyze a passage from the book that described the narrator processing overwhelming emotions.

“ChatGPT said, ‘Since she’s curled into a ball, this represents her wallowing in grief,’” she said. “It’s very surface level. It’s not the level of depth I would get from asking a person.”

Meanwhile, in her Theory of Knowledge class — a part of the International Baccalaureate program — students debated what constituted true artificial intelligence, considering how human influences could program biases and stereotypes into the tools.

Despite the flaws of tools like ChatGPT, Gereltogtokh said many students “use it all the time,” sometimes plugging in essay prompts and memorizing arguments ahead of in-class writing assignments, or even searching for answers to questions as their teachers are posing them in class.

Last year, she added, a group of 11th graders were caught using AI-powered tools to generate essays on “The Great Gatsby,” a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, after each of them wrote about “Alfonso.”

“There’s no character named Alfonso in ‘The Great Gatsby,’” Gereltogtokh said.

Though she sees the value of using AI-powered tools as personalized tutors, she fears those who rely on them too heavily risk losing their own critical thinking skills.

“When you use it too much, I can’t really tell what are your genuine thoughts and feelings, and what you just took from a chatbot,” she said.

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.