Vince Muccioli will never forget the terror he felt waiting for paramedics as one of his students lay unresponsive on the classroom floor, color draining from his face.

It was a quiet Friday afternoon in March 2022, and Muccioli, a math teacher at West Brooklyn Community High School, had given the student permission to lay his head on his desk.

When a classmate later nudged the student and he wouldn’t wake up, Muccioli knew something was very wrong. The student’s pulse was racing, but he was barely breathing, recalled Muccioli, who immediately alerted the school nurse and told a student to call 911.

The thought of a drug overdose crossed Muccioli’s mind, but in his 15 years teaching, he’d never seen a student have one and didn’t know how to respond.

Fortunately, paramedics arrived within 15 minutes and administered Naloxone, a nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an overdose. The student revived immediately, Muccioli said.

“Those 15 minutes,” Muccioli said, “could’ve been the difference between life and death.”

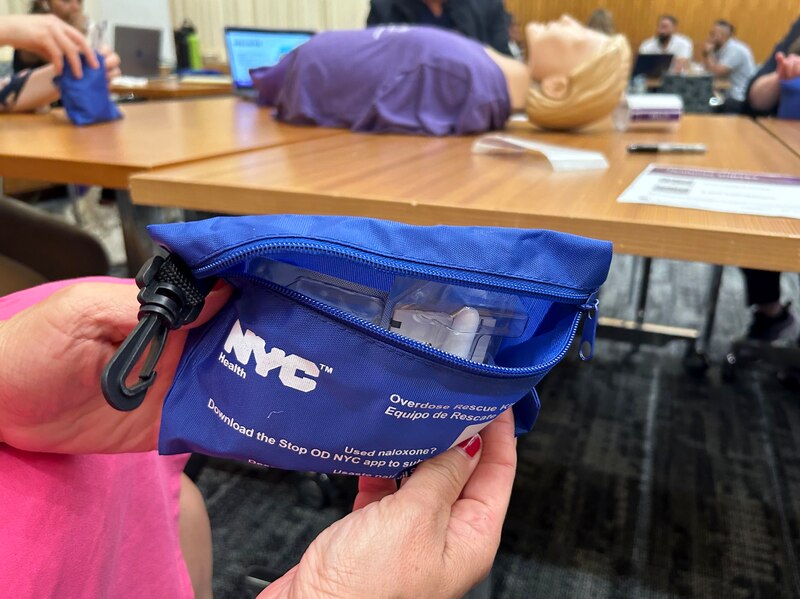

Soon after the incident, Principal Malik Lewis invited the nonprofit Harm Reduction Coalition to train his staff on using Naloxone and provide educators with their own kits.

Nearly two-and-a-half years later, the rest of the nation’s largest school system has moved in a similar direction. Every school now stocks Naloxone, all school nurses are trained on administering the overdose reversal agent, and the Education Department is bringing the training to additional school staff, city officials said. This spring, the city partnered with New York University Langone Health to train roughly 300 educators on administering Naloxone, said Kelleyann Royce-Giron, the Education Department’s head of substance abuse programs.

“We see what we’re seeing in emergency rooms … youth that are coming in with overdoses,” said Royce-Giron at a training for about 50 educators last month at NYU’s Tisch Hospital. “The biggest space that we can help our New York City youth is in the biggest school district in the world, the New York City public schools.”

The effort to bring Naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, into schools is part of a larger push to make the reversal agent as widely available as possible in the city, including in pharmacies, bars, and public health vending machines created by the city Health Department. Some NYPD officers also carry Naloxone, though a police spokesperson didn’t immediately respond to a question about whether school safety agents — the more than 4,000 unarmed police officers stationed inside public schools — carry it.

This push follows similar moves in school systems across the country. As of 2023, 33 states including New York had laws permitting schools to stock Naloxone, according to an analysis by Kaiser Health News. A smaller number went further by requiring schools to carry the reversal agent, the analysis found, though some schools and districts have resisted for fear that carrying Narcan would indicate a larger drug problem. Several districts in Long Island require schools to stock Naloxone, and the state offers a program for school districts to train staff in administering the reversal agent.

A 2023 survey by NPR found that 11 of the nation’s 20 largest school districts require schools to stock Narcan.

Overdoses in schools appear to be rare, but the risk is real, according to staffers and experts. Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second largest, required all schools to carry Naloxone and began training staff and volunteers after a 15-year-old died of an overdose at school in 2022.

In New York City, the number of 15- to 24-year-olds who have died from opioid overdoses has nearly doubled in recent years, from 48 in 2019 to 87 in 2022, the last year for which the city Health Department published data. Almost all of those deaths involved fentanyl, an extremely potent synthetic opioid that can be lethal in even small doses, or heroin, the Health Department analysis found.

Fentanyl is 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin and is often mixed into drugs like heroin or cocaine or found in counterfeit pills meant to look like Adderall or Percocet, NYU trainers told educators.

A Health Department spokesperson said the agency isn’t aware of any confirmed opioid overdoses of students in school last school year. Two city principals have told Chalkbeat they’re aware of Naloxone being administered on a student during school in recent years, though the Health Department spokesperson noted that the use of Naloxone doesn’t mean the incident was a confirmed opioid overdose.

In New York City, the 2023 death of a 1-year-old in a Bronx daycare from inhaling Fentanyl-laced dust captured the attention of the city and helped spur City Council legislation to stock Narcan in middle and elementary schools.

Larrisa Laskowski, a doctor of emergency medicine at NYU Langone Hospital and director of NYU’s Prevention Education Partnership, which works with the Education Department to offer Naloxone training, said the city shouldn’t wait for a similar tragedy in a public school.

“We can be proactive. We can get this perfect, very effective, very safe antidote in schools to protect young people as we’re trying to deal with the Fentanyl crisis in many other ways,” she said.

Educators point to gaps in Naloxone training, access

Teens are not immune from the growing opioid crisis that has gripped the city and the country in recent years, health officials said.

Educators across the city have reported an uptick in visible drug use during the school day since the return of in-person schooling following the COVID school shutdowns. Grappling with an ongoing mental health crisis, some teens have turned to substances as a coping mechanism. At the same time, the city’s drug landscape has rapidly changed due to the proliferation of smoke shops following the state’s rocky rollout of legalized marijuana.

“After we came back from the epidemic, I definitely see that there’s definitely a higher usage of students just self-medicating,” said Manolo Polanco, a dean at Fordham Leadership Academy in the Bronx, who attended one of the recent Narcan trainings. He said he’s had to call 911 several times for students feeling unwell after taking drugs, though fortunately none of the cases were serious.

Despite the recent progress in trainings, some educators worry there are still gaps in the city’s efforts to ensure schools are prepared to respond to student overdoses.

At Brooklyn Technical High School, the city’s largest school with nearly 6,000 students spread across eight floors, “having one or two nurses dealing with an overdose … means nothing because you won’t get to them in time to save their life,” said a staffer at the school, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to talk to the media.

Naloxone training should be mandated for multiple staffers at each school, similar to the way epi-pen training is mandatory for multiple staffers at schools where a student has a documented risk, the Brooklyn Tech staffer said.

Education Department officials said that anyone trained in Naloxone can carry and administer it at school, but the Brooklyn Tech staffer said that message “is not going out to everyone,” noting that many staffers at the school are under the impression that only the nurse can administer the reversal agent.

The city has also long struggled with nursing shortages: Roughly 140 schools didn’t have a nurse before the pandemic, according to the nonprofit Advocates for Children. The city used $65 million a year in one-time federal pandemic aid to hire an additional 400 contracted school nurses, but that money expired this year and was not replaced in the budget, according to advocates.

An Education Department spokesperson said officials are still “placing [a] nurse in every school and do not expect schools to be without a nurse,” but didn’t elaborate on where the funding will come from.

Trainings seek to make educators confident first responders

The technical requirements of administering Naloxone are fairly simple. It’s a nasal spray that doesn’t require any special technique and has no adverse side effects, according to Laskowski.

But the training sessions for school staffers are less about the technique than about giving educators “the confidence they need to feel like they can act,” Laskowski said.

That’s part of why Laskowski said she’s pushed back against suggestions to make the training sessions virtual, even though that might make them accessible to more people. It’s important to build the kind of comfort and familiarity that comes with in-person training, she said.

Royce-Giron — who oversees the school system’s roughly 260 Substance Abuse Prevention and Intervention Specialists, or SAPIS — appreciates the chance to dispel some commonly held concerns, including assuring attendees that fentanyl can’t be absorbed through the skin. She also takes pains to remind the educators that the state’s “Good Samaritan” law offers legal protection to people who intervene to try to save someone during an overdose.

Sherille Sheppard, a special education teacher who attended the training, said she found it “very informative.”

“I was glad to get the hands-on piece to really show me how easy it is to use Naloxone,” she said. “It’s really just as easy as using a nasal spray.”

Polanco, the Bronx high school dean, left the training feeling “a little bit more prepared” to identify an overdose. “Before, I don’t know if I even would have been able to identify it, to me it would have just been a kid passed out.”

At West Brooklyn Community High School, the importance of carrying Narcan wasn’t the only lesson to emerge from the close call with the student overdose.

The incident was a vivid reminder to staff that no matter how ill-equipped they might feel in the moment to deal with some of the complex challenges students are facing – from serious drug use to suicidal ideation – it’s vital to engage.

“When a student comes to confide in you, talk to them,” Muccioli said. “No matter how heavy the situation is, talk to them. Because there’s a window where they might tell you and only you.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org .