Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

In the panicked moments after immigration agents detained Dylan Lopez Contreras in a Manhattan courthouse last month, his mother dialed a familiar number.

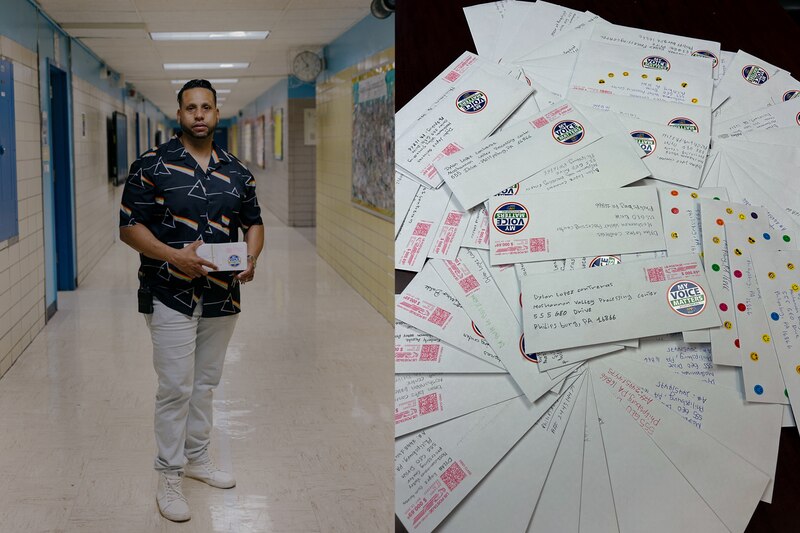

It was Hedin Bernard, a counselor at her son’s high school, English Language Learner and International Support Preparatory Academy, or ELLIS Prep — a nod to the famous island through which millions of immigrants entered New York City last century.

“He’s always given us support,” said Raiza, who asked to use only her first name for fear of retaliation. “He knows my son is a good kid. They’ve taken him in there, and they’re always available to help.”

Dylan’s arrest two weeks ago — the first known case of a New York City public school student detained by immigration agents in President Donald Trump’s second term — has galvanized local opposition to federal immigration policy and sparked a fierce debate about the city’s role in protecting immigrant students. His detention also has put a spotlight on the unique brand of public education offered by schools like ELLIS Prep.

Within an already specialized group of schools serving new immigrants, ELLIS is unique: It’s one of just a handful of schools citywide geared toward students who have been in the country for less than a year and are considered “over-age” to start at a traditional high school. Such students often struggle to find schools willing to enroll them and face among the steepest obstacles to finishing high school. Some, like Dylan, start at ELLIS as old as 19. (State law entitles students to remain in public school through age 21.)

The school’s model represents an expansive vision of public education, embracing students like Dylan, regardless of immigration status, with academic and emotional help as well as connecting them with housing, food, and legal support with an explicit goal: getting them to college and out of poverty. But that mission stands in contrast to the policies of the Trump administration, which has ramped up deportations, rolled-back longstanding protections from immigration enforcement at school, and sought to curtail public funding for undocumented students pursuing higher education.

In the wake of the arrest, while some social media commenters questioned why Dylan, a 20-year-old native of Venezuela, was even enrolled in a public high school, staffers at ELLIS set about trying to get their student back.

The school mobilized to quickly connect Dylan and Raiza with resources while helping its other students — many worried about their own legal cases — make sense of the news.

In some ways, it’s a crisis that ELLIS was tailor-made to confront — drawing on its 17 years of expertise, close relationships with families, and extensive past experience supporting immigrant students through all manner of out-of-school challenges, including detention by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

“If it was going to happen, in a strange way, I’m glad it happened to us,” said Norma Vega, the school’s founding principal, who designed and launched ELLIS in 2008.

“They thought this was some kid they were going to pick up and no one was going to miss him,” she added. “That was a mistake.”

But ELLIS’ particular population and mission have also made it that much more susceptible to the ripple effects of Dylan’s arrest.

Breaking the news of Dylan’s arrest to other students felt almost like sharing news of a suicide, said Bernard, causing other students to immediately question: “Is it going to happen to me? Is it going to happen to more? What if somebody is going to court next week?”

One student told the school a little over a week after Dylan’s arrest that her family was planning to return to the Dominican Republic after hearing about relatives arrested under similar circumstances as Dylan.

In a matter of days, the school, one of seven nestled in the hulking John F. Kennedy High School campus overlooking the Harlem River in the Spuyten Duyvil section of the Bronx, had convened meetings with students and staff. They also launched a letter-writing campaign that yielded hundreds of hand-written notes of support to be delivered to Dylan at his Western Pennsylvania detention center. A teacher’s father created a GoFundMe page that has so far raised nearly $40,000 for the family.

“They’re always writing to me, calling me, seeing if I need anything emotionally,” Raiza said in Spanish. “So much, so much support.”

For Vega, the past few weeks have been a lesson in “how important it is to not function out of fear.”

“The more we continue to support, the more other people will be willing to support,” she said.

‘In a panic’: ELLIS leaps into action

At first, Bernard, the school counselor, didn’t see Raiza’s calls on May 21. He was wrapped up in one of the many small crises that fill his days.

A fixture and founding ELLIS staff member, Bernard, a bilingual counselor with Dominican roots, serves as a sounding board for students, families, and staff on everything from teen relationship drama to legal crises. He’s one of roughly a dozen people on the staff of about 40 dedicated to supporting the school’s 250 or so students with challenges beyond the classroom.

When Bernard noticed the multiple missed calls and finally got in touch with a distraught Raiza, he leapt into action.

“I was in a panic,” he said.

Bernard called every legal organization he could think of. He reached someone at Metro Baptist Church in midtown Manhattan, which houses multiple groups supporting migrant families, and connected Raiza with an advocacy group that provided case management and pro bono lawyers from the New York Legal Assistance Group, or NYLAG.

ELLIS counselors have long taken on the role of helping students find lawyers. Over multiple years, Bernard assembled an 18-page packet of pro bono lawyers that he distributes to students. But finding pro bono legal help has become more difficult this year, he said.

Because of the rapid-fire changes to immigration enforcement since Trump took office, routine hearings that used to be safe to attend without a lawyer now often require legal representation, said Melissa Chua, a co-director of the Immigrant Protection Unit at NYLAG who has been overseeing Dylan’s case. That has “exacerbated the distance between the need and the ability to provide help,” she said.

Bernard knew what to do when Raiza called, in part, because it wasn’t his first time facing this situation. Nearly a decade earlier, the school successfully rallied for the release of a student detained by immigration authorities under former President Barack Obama.

“It was all hands on deck,” recalled Bernard of that past effort.

But Bernard feared this time might be different. The Trump administration has rolled out unprecedented enforcement tactics, arresting immigrants at courthouses and thrusting them into fast-track deportation proceedings. Detainees, including Dylan, are routinely whisked around the country from state to state, making it more difficult for their lawyers to reach them. And Bernard wasn’t sure whether Trump administration officials would respond to pressure in the same way the Obama administration had. ICE under Trump is seeking to push deportation to record levels as part of what administration officials say is a necessary corrective to overly permissive immigration policy during former President Joseph Biden’s tenure.

For ELLIS, the incident raised serious questions about whether the standard advice staffers had always given students — attend court dates — still made sense during the second Trump administration.

Vega, the school’s principal, wrestled with those questions the night of Dylan’s arrest: “How do I counsel them? What do I tell them? What do I say?”

‘It’s going to be hurtful:’ News of Dylan’s arrest spreads

Any hope that school staffers had that Dylan might be released quickly began to dim by the third day, when they learned he had been shuttled from a detention center in New Jersey to another in Texas.

Vega, preparing to share the news with students and teachers on Friday morning, struggled against her own anger and frustration about Dylan’s condition while seeking to reassure the school community.

In a cavernous science classroom filled with raw spaghetti sculptures, dozens of students filed in for a meeting with Vega and several of the school’s counselors.

“What I’m about to share with you is really important. It’s going to be hurtful,” Vega began. “On Wednesday, we were informed that one of our classmates was detained.”

Vega urged them to come talk to the staff if they have an upcoming court date.

“There’s no reason for you to feel ashamed, embarrassed,” she told them. “I know each of you by name. I know your stories. Everybody here knows who you are, because you matter.”

Many of the students in the crowded science classroom were still in the early stages of learning English and struggled to understand all of the details of Vega’s message. It wasn’t until after the meeting, when they began clustering in small groups to translate and discuss that it began to sink in. In hallways decorated with photos of students on international trips, billboards with college acceptance letters and Know Your Rights guidance, African students huddled to parse through the news in French, while Latin American students whispered in Spanish.

Many of them made their way to Vega’s office, a central gathering place where the door is almost never closed and students often come in to pray, use the bathroom, or eat.

“Noooo, Dylan,” said one junior as he pieced together the details of who had been detained.

Bernard joined one circle of Spanish-speaking students standing in the doorway of Vega’s office to help translate.

A boy with braids, purple headphones resting around his neck, and a gray Walt Disney sweatshirt with a Mickey Mouse logo cast his eyes down as Bernard explained. He had a court date coming up.

‘You’re not alone:’ Students offer their support

Public attention — and outrage — over Dylan’s case has continued to mount. Last Thursday, hundreds of Dylan’s supporters rallied on the steps of the Education Department’s downtown Manhattan headquarters demanding his release. Meanwhile, his lawyers filed a “habeas corpus” petition alleging Dylan’s detention violated his due process rights. Even Mayor Eric Adams, who initially sought to distance himself from the case, voiced support for Dylan as his law department filed a friend-of-the-court brief in his legal case.

At ELLIS, staffers wanted to come up with their own way to make a quiet statement, while also giving their other students a chance to process their feelings.

On the same day as the rally, students and staffers set aside time during class to pen their thoughts for Dylan in handwritten notes, then sealed them in envelopes to ship to the Moshannon Valley Processing Center in Western Pennsylvania. The Department of Homeland Security did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the letters.

The notes were a mix of familiar teenage concerns and heartfelt offers of support.

One student recalled that Dylan, who had recently dyed his own shaggy hair purple, offered to color their hair. “Truthfully, I like my hair now more because of you,” the friend continued in Spanish. “I want to change it to blonde or blue now … what do you think?”

Another student, a fellow native of Venezuela, tried to boost his spirits by appealing to their shared national pride.

“It’s important to keep in mind that Venezuelans ‘NEVER GIVE UP.’ We’re warriors, strong, made to keep going.”

And many others let him know that the entire school was behind him.

“I want you to know the school will do everything possible for you and keep your mom informed of everything,” one student wrote.

“We all confront our individual battles,” she continued. “And yours is very difficult, inhumane, and unjust. But you’re not alone.”

Earlier this week, Raiza informed the school that ICE declined to deliver the letters to her son.

They were marked, Dylan told her, as contraband.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org