Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

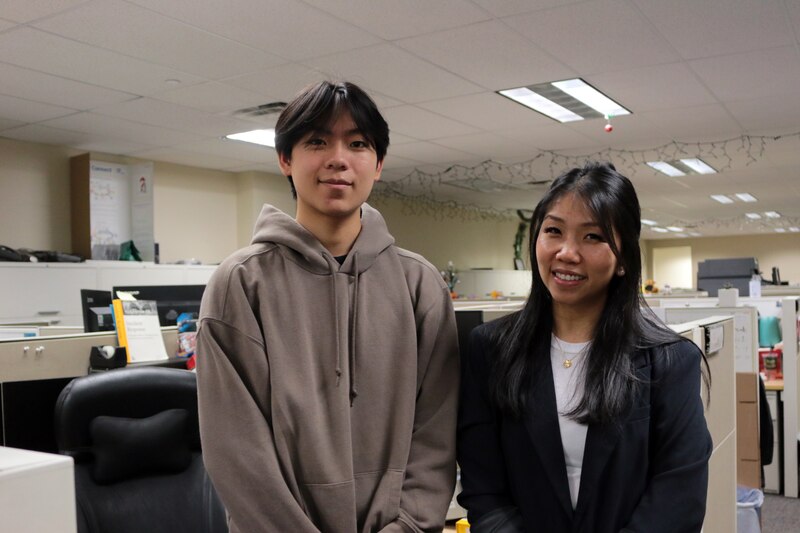

Shortly after Addison Wang settled in at his desk on a recent Tuesday in a windowless room at the Education Department’s information technology office, an alert landed in his inbox.

It said an email was circulating among department employees directing them to a potentially malicious website. His task was to determine if anyone had clicked on it.

Wang is not a traditional employee at the school system’s Division of Instructional and Information Technology, the department that helps safeguard digital infrastructure for more than one million students and staff.

He’s a 18-year-old senior at Chelsea Career and Technical Education High School.

Over the past two school years, Wang has spent about four hours a day, four days a week, working for the Education Department, often leaving his Manhattan school midday to hop a subway to its Downtown Brooklyn technology office.

Wang is one of 389 student apprentices across the city’s public schools who split their school days between traditional classes and job sites, part of a growing initiative that city officials hope will help ease students into careers with solid wages at companies like Amazon or Accenture, or even city government. The average starting wage among apprentices is $17.90 per hour; Addison earns $16.50, the city’s minimum.

The program, called the Career Readiness and Modern Youth Apprenticeship, is part of a broader push under Mayor Eric Adams to give students access to paid work opportunities for in-demand fields well before graduation — though city officials have struggled to scale it up as quickly as promised.

In 2022, the Education Department vowed to place 3,000 students in apprenticeships within three years. So far, only 528 students have participated.

Wang said he was drawn to the apprenticeship because “I was really wondering how jobs and workplaces differ from my imagination.”

On that Tuesday afternoon, the teen quickly launched into troubleshooting mode to sort out if any employees were exposed to the suspicious message. After a little trial-and-error and some prompting from a supervisor who peered over his shoulder, Wang ran a search of the city’s email system.

Only eight Education Department employees received the scammy message. No one had clicked on it.

Apprenticeship’s time commitment can be a sticking point

At first, Wang was skeptical of the apprenticeship program.

He knew it would be difficult to participate in after-school activities or get home in time for family dinners. His work day doesn’t wrap up until 5 p.m, and the commute home to Staten Island involves multiple subway lines and a bus — taking well over an hour. It has also threatened to complicate his social life.

“A lot of friends go and hang out after school,” Wang said, “but then you can’t because you have work.”

The training requirements gave him pause, too. Apprenticeship candidates must participate in a course to help prepare resumes and polish interview skills, and they compete for slots among students across the city without a guarantee an employer will hire them. Later, they attend a summer program to learn about professionalism and tools like Excel and Outlook, which comes with a $1,800 stipend.

The financial incentive proved to be a key selling point. Wang uses a portion of his wages to help pay household bills to support his parents who immigrated from China more than 20 years ago. His mom works as a nail spa technician and his dad does freelance construction projects.

“I’m proud that I can help the family and relieve the stress,” Wang said. The rest goes toward eating out with his friends or trips.

After working as an apprentice for more than a year, Wang began to see some of the benefits of spending so much time at one job site. While some of Wang’s time goes to basic administrative functions, like assigning requests that come in to the appropriate staff member, he has been at the Education Department’s technology office long enough to participate in more complex projects.

After the office received a deluge of complaints about Chromebooks that wouldn’t connect to school Wi-Fi, Wang brought one to school to troubleshoot. The teen helped figure out that the problem had to do with the Chromebook operating system getting tangled up with the Education Department’s internet filters that block certain websites.

“He provided some really good insight on his experiences with Chromebooks,” said Jenny Wong, a leader of the security incident response team and Wang’s supervisor. “We’re like, ‘Oh my God, we never have thought of that.’”

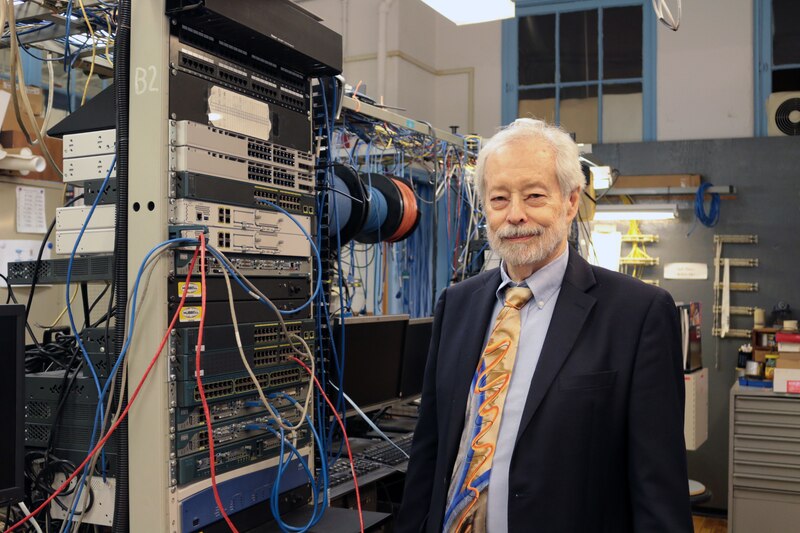

Some of Wang’s teachers have asked him to draw on his apprenticeship experience during regular classes. At Chelsea CTE, Wang is on the Cisco Networking track, which trains students how to set up computer networks and allows students to earn an industry credential by the end.

John Tebett, who teaches the Cisco sequence, asked Wang to present about his work experience to create “a direct tie-in between what he’s doing there and what we were talking about” in class, Tebett said.

To Wang, one of the most valuable aspects of the apprenticeship has had little to do with technical training. It’s learning how to negotiate with adults.

After Wang’s supervisor approved the teen to work remotely from his school building twice a week, allowing him to participate in student government, a new problem cropped up. He needs his phone to communicate with his job site, but his school recently instituted a cellphone ban that requires students to put their phones in locked fabric pouches all day.

The school’s principal was reluctant to grant an exception. But Wang persisted, and they ultimately reached a compromise: The school offered up a velcro pouch that Wang can open himself when he’s working on apprenticeship tasks.

Advocating for himself to adults is “definitely something I’ve become comfortable with,” Wang said. “I still see, like, teenagers in high school struggle with [that].”

NYC has yet to fulfill promise to dramatically scale up apprenticeship program

Expanding work-based learning is one of Adams’ top education priorities. And he visited Chelsea CTE in February, flanked by Wang, to highlight the apprenticeship program. But the city has struggled to reach as many students as initially promised.

A department spokesperson said they are still aiming to reach their 3,000-student target, though they did not offer a timeframe. Officials said they are working to adjust the program to account for needs in various industries, such as differing expectations about how long it should take to master the relevant work skills.

Experts noted that apprenticeships have historically been difficult for schools to pull off because they require identifying employers willing to take on teens and enough supervision and training to ensure it’s a meaningful experience.

“Linking high school students with workforce career prep is hard,” said John Sludden, a research analyst at New York University’s Research Alliance, which is working with the group MDRC to study New York City’s CTE programs. “Schools aren’t built for this,” he added, “employers aren’t built for it.”

At Chelsea CTE, staff previously made cold calls to find companies willing to accept students for work-based learning experiences. Now, the city is leaning more on intermediaries like CareerWise, a nonprofit that is heavily involved in lining up job sites and helping schools manage the apprenticeship program. That “has taken a big load off of schools,” said Principal Jaivelle Reed.

Finding students who are willing to participate remains a challenge and the number of apprentices at the school has incrementally grown. About 12 students on the campus are participating. Students often bristle at the time commitment and those who aren’t on an accelerated path to graduation often can’t afford to miss four hours of school several times a week while still earning credits and passing state exit exams.

For those students, “my concern is that something will have to give: either the academics or the apprenticeship,” Reed said. “I don’t want either to suffer.”

Still, Reed said there are success stories he hopes will entice more students to join. After one of the school’s seniors completed an apprenticeship at Accenture last year, the company offered her a $70,000 a year job as a full stack developer. Although the student initially planned to go to college, she accepted the job. (Accenture also offered to subsidize college if she chooses to attend, Reed said.)

City officials hope that the apprenticeships give more students the option of launching a solid career without feeling obligated to attend college, though many jobs in lucrative fields still require a degree. Several districts across the country, including New York City, are moving away from the idea that college is the right path for everyone.

For his part, Wang wants to focus on college and career simultaneously.

He’s planning to enroll at The City College of New York honors program to study computer science, but is also not quite ready to leave the Education Department’s technology division. The apprenticeship program gives students the opportunity to continue for a year after graduation.

This fall, Wang is once again planning to juggle school and work.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex atazimmerman@chalkbeat.org.