This is part one of a two-part series. Read the second story here.

In the hours after one of his students was apprehended by federal immigration agents, Hedin Bernard was on the phone nearly nonstop. He’d comforted the student’s mother. He’d called advocates and lawyers.

And in the moments in between, the school counselor had agonized over how he would tell his other students at ELLIS Preparatory Academy that Dylan Lopez Contreras, a first-year student from Venezuela, had been detained.

He was particularly worried about telling one student.

Bridget, an 18-year-old Ecuadorian immigrant, was a friend of Dylan’s, close enough that he shared arepas with her at lunch. Bernard knew that Bridget and her mother, Marta, were dreading their own upcoming court date and immigration check-in, and word of Dylan’s arrest would get out soon. He wanted Bridget to hear it from him. In her eight months at ELLIS, Bridget had often retreated to his cramped office and sunk into a plush black bean bag whenever her stress became too much to bear.

For Bridget and Marta, who asked to use pseudonyms because they fear immigration enforcement, life in New York City as undocumented immigrants had been defined by hardship. They had bounced between three friends’ and relatives’ apartments before landing in a homeless shelter in midtown Manhattan. Marta collected cans, making about $20 a day, and was often unable to afford food.

Their anxiety had increased since President Donald Trump began his second term in January, promising to launch the “largest deportation program in American history.” Fearful that any wrong move could get them detained, separated, or deported, the mother and daughter tried to stick together. Marta even used some of her precious dollars to commute with Bridget to school.

With Dylan’s arrest, Trump’s enforcement campaign had arrived at the school’s doorstep.

Founded in 2008, ELLIS’ mission is based on the belief that all of its students, including undocumented ones, can build a future in the U.S. The Bronx school has pushed hundreds of newly arrived immigrants into college and out of poverty with a playbook staffers have honed for years, relying on strong relationships with students and a sophisticated network of support for families’ needs. For Bridget and Marta, ELLIS often felt like the only public institution with its arms open in a city and country that otherwise seemed not to want them.

“They’ve given her a lot of hope,” Marta said in Spanish. “It’s the reason we don’t want to leave.”

But over the last seven months, ELLIS educators have been forced to confront a fundamental question: Could the school continue to help its students work toward a life in this country when the federal government was sending the message that many of them weren’t welcome here?

Bernard stood in his office with Bridget that Thursday afternoon in late May, explaining how plainclothes agents had seized Dylan. He watched her smile fade.

He knew the arrest was stirring up painful memories from Bridget’s own immigration journey.

Bernard had helped Bridget find free food and clothes, navigate the city’s complex shelter system, and access legal advice. He had celebrated with her when she’d passed the Algebra I Regents exam required for graduation. He had seen her face light up talking about plans to attend college and become a veterinarian.

But now, Bridget just wanted to know if her friend was OK. And Bernard didn’t know what to tell her.

Starting high school, again

In Guayaquil, Ecuador, Bridget had been a strong student, just one year away from finishing high school. But gangs had become so prevalent in her neighborhood that she no longer felt safe walking home from night classes.

Bridget’s oldest sister, now 38, came up with the idea of immigrating to the U.S. so Bridget could continue her education.

Bridget, who loves Korean pop music and animals, was devastated to part with her dog, Molli, a small white Pekingese, but excited for what the future held. Marta, anxious by nature, worried most about the trip, but agreed to go for Bridget’s sake.

“It’s not going to be my fault that her dream dies,” Marta decided.

The women had one advantage: Marta’s middle daughter, who left Ecuador six years earlier at age 19, had an apartment in the Bronx with her husband and two kids, giving the rest of the family a roadmap and a place to stay.

But the journey quickly veered off course. They got stuck for about a month in Mexico, losing almost all of their belongings. They arrived in the U.S. in April 2024 with just the clothes on their backs and a few prized possessions: a Bible, a hymnal, and a light brown stuffed mouse named Mickey who remains attached to Marta’s fanny pack.

As soon as they crossed into Texas, the women were detained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and separated. As Bridget was a minor, she and Marta were released with plane tickets to New York. Her eldest sister was imprisoned by border agents for a month before being deported to Ecuador.

Bridget and Marta have clung to each other ever since.

In New York City, Bridget and Marta moved in with Bridget’s middle sister. Sharing a small apartment with her family of four wore on everyone. Marta struggled to find work. Then at their first check-in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, officials encouraged Bridget to enroll in school.

Bridget got a list of four public schools from an Education Department enrollment center, but three rejected her, saying they didn’t have space and didn’t accept older students.

Last on the list was English Language Learners and International Support Preparatory Academy, or ELLIS, a nod to the famous New York City island through which millions of immigrants have passed. That’s where Bridget started classes in September 2024.

She was part of a historic wave of roughly 50,000 migrants who have enrolled in New York City schools starting in summer 2022, according to the city’s estimates — a pattern echoed across the country as cities like Denver, Chicago, and Los Angeles absorbed thousands of families fleeing Latin America, Africa, and other parts of the world.

The influx has posed new challenges, as schools scrambled to hire bilingual staff, add counselors and social workers to help students struggling with trauma from their journeys, and assist older students seeking to graduate quickly. But the new students have also been a boon for school districts previously losing students and funding. In New York City, former schools Chancellor David Banks described the migrant influx as a “godsend,” saying they staved off potential school mergers or closures.

ELLIS, a small school with 275 students, is one of only a handful in the city explicitly designed to enroll older, newly arrived students, who face a steep climb to graduation. At a meeting with the guidance team early in the school year, Norma Vega, ELLIS’ founding principal, told staffers: “Our 67% graduation rate is someone else’s 98%. The amount of work everyone does to get each kid to the finish line is beyond comparison.”

Unlike other schools, ELLIS requires all new students, regardless of age or how much high school they’ve completed in their home country, to enter as first-year students. The model ensures that students leave school with the English fluency and familiarity with the American education system they need to succeed in college and beyond.

Starting high school again made Bridget nervous: Her only knowledge of American high schools came from movies. She worried about speaking English and making friends. But she was also hopeful. She and her mother had traveled nearly 3,000 miles for this chance.

ELLIS Prep braces as Trump takes office

What Bridget and her mother hadn’t counted on was arriving in the U.S. at a moment when a growing number of Americans saw illegal immigration as a critical problem. A July 2024 poll found that 55% of Americans said they wanted to curb immigration — the first time since 2009 that a majority of the country expressed that view.

In the run-up to the presidential election, Trump focused his campaign on immigration, though he promised to target his deportation efforts on violent and dangerous criminals that most Americans agreed should be expelled from the country.

Even some ELLIS students offered support for Trump’s immigration platform in class discussions, a history teacher said.

Some conservatives questioned, too, whether the country should continue to educate undocumented students, a practice codified in the 1982 U.S. Supreme Court case, Plyler v. Doe. Critics, including the authors of the influential Project 2025 domestic policy blueprint, argued that the recent influx of migrants put an unsustainable strain on public schools, to the detriment of U.S.-born students.

School systems don’t track the immigration status of students, making it difficult to know how many undocumented students have enrolled in public schools. But an estimated 850,000 undocumented children are living in the U.S., according to Pew Research Center. Another estimated 4.4 million U.S.-born children have at least one parent who is undocumented — an umbrella term describing migrants without a valid visa or legal residence.

After Trump’s win in the 2024 election, Bernard, the school counselor, noticed an uneasy quiet fall over the school.

A founding ELLIS staff member with a dry sense of humor and encyclopedic knowledge of history and geography, Bernard kept a fourth-floor office that was seldom empty, with visitors ranging from a teen caught vaping marijuana outside to a colleague looking to vent.

Bernard had lived his own version of the immigrant success story. His parents came from the Dominican Republic and ran a grocery store on Manhattan’s Lower East Side so they could afford Catholic school. He wanted to give his students that same support, and he often served as a kind of stand-in family member for students who’d left their homes and loved ones thousands of miles away.

In the days after the November election, Bernard expected a queue of students with questions and concerns. But few students wanted to talk about the new administration. It felt like everyone was just “waiting for the other shoe to drop,” he said.

That happened the week of Jan. 21, after Trump delivered a fiery inauguration address vowing to “begin the process of returning millions and millions of criminal aliens back to the places from which they came.” The next day, Trump rescinded longstanding guidance prohibiting ICE from carrying out immigration raids at or near schools.

Absences at ELLIS skyrocketed, like they did across the city. Bernard and other counselors tried to reach families by phone and WhatsApp to assure them it was safe to attend. Many students, including Bridget, said they wanted to wait a couple of days.

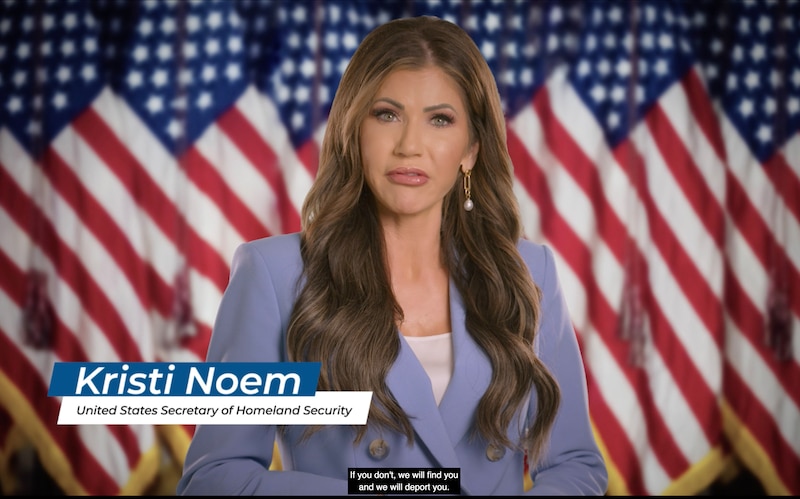

A week later, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem posted a video of an ICE raid in the Bronx — one of several in neighborhoods surrounding ELLIS — accompanied by the message: “Getting the dirt bags off the streets in New York City this morning.”

ELLIS students saw videos of ICE on social media and heard rumors of immigration agents showing up in their neighborhoods. ELLIS staffers posted “Know Your Rights” guidance on bulletin boards in the hallway, and Vega, the principal, went around to classrooms instructing students on what to do if they came into contact with immigration agents.

“They wanted to know: ‘Is someone going to come pick me up?’” said Vega. “The answer in this building is that every student here is going to be protected. The goal is to make sure every student … is aware of their rights. That they’re entitled to be in school.”

Most of the ELLIS students who skipped school quickly returned. But a few — like a senior who missed more than a month of school and only came back after Vega did a home visit — were paralyzed by fear of immigration enforcement.

The threat of deportation had become another obstacle standing between ELLIS students and graduation, one that the staffers faced like any other challenge: with a belief that caring educators can keep students on track. But Trump’s message was proving powerful, too.

Paving a path to college for immigrant students

Midway through the school year, Bridget had come on ELLIS’ radar as a first-year student with unusual maturity and potential who dealt with significant stress outside school.

Bridget had proven a quick study in English and math. Her attendance was excellent, and her grades were almost all As and Bs. Her fluency in English had progressed, and she’d made an impression on friends and educators with her generosity and kindness.

Vega believed Bridget would earn a scholarship to a good college if she made it to graduation.

In her 17 years leading ELLIS, Vega had developed a kind of radar for the barriers that could keep each student from making it to graduation and college.

The daughter of a tight-knit Puerto Rican family, Vega attended public schools on the Lower East Side until her family was priced out to the Bronx. Before founding ELLIS, she had worked as a social worker and principal of another school for new immigrants, but she was frustrated by the lack of options specifically geared toward older newcomers.

Starting and leading ELLIS had been a labor of love, propelled by the small schools movement under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

When it came to Bridget, Vega and Bernard quickly realized Marta’s anxiety about immigration enforcement was taking a toll.

Bernard asked Marta for permission to bring Bridget on an ice skating field trip in Manhattan. Marta refused, too worried about what could happen to Bridget to give her consent. “‘She’s all I have,’” she told Bernard.

The school didn’t give up. In early March, Bernard and Vega invited both Marta and Bridget on a school trip to John Jay College — a CUNY institution with an especially well-developed set of resources for undocumented students.

For Vega, it felt like a turning point in getting both Bridget and Marta to buy into the school’s guiding vision: that a college education and a future in the U.S. are within reach.

“[Marta] started crying when she realized there’s hope,” Vega recalled.

The trip also gave Vega a chance to offer a delicate piece of advice she often shares with fearful parents — one she sensed would be particularly relevant for Marta and Bridget, who were so fiercely attached: If Bridget were to build a life in the U.S., her mother would need to loosen her grip and let her explore.

Staying the course despite rising threats of deportation

On a Friday afternoon in mid-March, Vega was driving her kids to a martial arts tournament, listening to bachata on a music streaming app and trying not to think about work, when she heard an ad that made her jaw drop.

In a Department of Homeland Security ad, Noem said, “President Trump has a clear message to those that are in our country illegally: Leave now.

“If you don’t, we will find you, and we will deport you. You will never return.”

Vega was horrified. She took the app off her phone. But the ad popped up on another platform later that day.

In the months since Trump took office, Vega had done all she could to insulate her school from anti-immigrant political rhetoric. But listening to the ad, it occurred to Vega that if she was having difficulty escaping the fear campaign, it must be even harder for her students and their families.

“What they’re trying to do,” she said, “is scare people into leaving.”

Just weeks earlier, she’d learned that a student who stopped coming to school after the presidential inauguration returned to Colombia — the first time Vega knew of that happening in the school’s 17-year history.

The ad, part of a multimillion-dollar campaign playing on radio, TV, and music streaming platforms across the country, was one prong of the administration’s quickly escalating immigration enforcement tactics.

Agents had detained U.S. green card-holders at airports, including a German citizen who had lived in the country for 17 years. The Trump administration had invoked an arcane law, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, to deport hundreds of migrants to a notorious mega-prison in El Salvador. One of them was a 19-year-old Venezuelan living in the Bronx. He could have been an ELLIS student, Vega thought.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams, meanwhile, had signaled his willingness to cooperate with the enforcement push locally. Trump’s Justice Department succeeded in getting federal corruption charges against Adams dropped, in part, so he could better support the administration’s immigration agenda. After a meeting with Border Czar Tom Homan, Adams vowed to reverse a city policy barring ICE from making arrests on Rikers Island.

The school had several annual field trips approaching, including an overnight trip to Washington, D.C., for first-year students. The trip felt fraught with new risk this year, and some staffers and parents — including Marta — had expressed concerns. But Vega knew how important it was to give her students, all of whom came from low-income households, the same type of rich cultural experiences as students from more affluent families.

Vega believed, too, that going to the nation’s capital, where federal officials crafted the immigration policies shaping the lives of ELLIS students, would send a powerful message that the school would not cow to fear.

“We’re going. We’re going,” Vega said as the school began preparations for the trip to Washington.

A mother and daughter from Ecuador confront their future in NYC

By mid-April, Bridget and Marta were growing increasingly nervous about their upcoming court hearing and ICE check-in. Despite their best efforts, they hadn’t found a lawyer to represent them in front of an immigration judge in June.

But with Bernard’s recommendation, Bridget and Marta visited a Manhattan church that helps connect immigrants to services, securing a phone appointment with a screener for a legal organization.

They took the call at ELLIS in a storage room that Bernard unlocked so Bridget and Marta could have privacy.

The screener explained that winning an asylum claim — the most common path to legal status for Latin American migrants — would be an uphill battle given the high bar to prove they faced a specific fear of violence or persecution in Ecuador.

But there was another possible legal route. The screener suggested that Bridget would be a strong applicant for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, a type of legal protection available to immigrants under age 21 who had been abandoned or neglected by one or both parents. Bridget told the screener her father had never been a part of her life.

The protection would only apply to Bridget, not Marta.

After the screener hung up, the mother and daughter sat quietly for a few moments. Marta began to cry, and Bridget wrapped her arms around her.

“Maybe they’ll let her stay and send me back home,” Marta said, as if thinking out loud, before turning to Bridget. “Don’t help me, help your sisters. Be humble, love your sisters, keep moving forward. Don’t be like me and be nothing, and have to collect bottles.”

Bridget glanced at Mickey, the dirt-encrusted mouse attached to Marta’s fanny pack who’d been with them since they left Ecuador.

She thought about all they’d been through and all of the sacrifices her mother had made to enable her dream of pursuing an education in the U.S. She couldn’t imagine life here without her mom.

Over the days and weeks ahead, Bridget’s resolve to remain in the country began to falter.

It would be up to her school to keep it alive.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org