This is part two of a two-part series. Read the first story here.

Fifty students stood in front of the White House, with its manicured lawn and billowing American flag. They hailed from countries like Ecuador, Nicaragua, Senegal, and Mali. They spoke Spanish, French, Pulaar, and English. Some wore hijabs.

Like other tourists on that April day, the students on a field trip with their Bronx high school posed for a group photo.

Several asked if President Donald Trump was inside. One had told an English teacher before the trip that he wanted to ask Trump why he was so anti-immigrant. Others joked, “Trump is gonna get you,” not knowing the president’s mass deportation campaign would soon sweep up one of their classmates.

In the months since Trump took office, Norma Vega, the principal of ELLIS Preparatory Academy, had vowed to stick to the same practices that for years had helped her school lift immigrant students into college and out of poverty — even as fears grew. That meant forging ahead with the trip to Washington, D.C., an ELLIS tradition that strengthened first-year students’ connection to the school and exposed them to U.S. history outside the classroom.

“We can’t function out of fear,” Vega said before the trip. “We just can’t.”

The trip was particularly meaningful for 18-year-old Bridget, an undocumented first-year ELLIS student from Ecuador who almost stayed behind because her mom, Marta, was scared of spending two days apart. She marveled at the size and beauty of the White House and the clean streets and white limestone architecture of the city. The free night in a Holiday Inn Express and hotel breakfast the next day felt like an escape from the hardship and fear that marked her life in New York City.

“It’s very beautiful. It’s like a vacation,” she said in Spanish.

But for both students and staff, the glow of the trip was short-lived. Three weeks after they returned, their classmate, Dylan Lopez Contreras, was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

Dylan’s arrest marked an aggressive new phase of immigration enforcement and a turning point for ELLIS. Federal policy reached into the school as never before, threatening ELLIS’ ability to recruit new students, retain its current ones, and send its graduates to college. Even as Vega and other ELLIS staffers clung to the approach that had long made the school successful, they began to fear their model of education may not survive the Trump administration.

Nowhere was the challenge facing ELLIS more apparent than in the school’s attempts to keep Bridget on track.

Bridget had several key ingredients for success at ELLIS: a deep relationship with staffers like counselor Hedin Bernard, a firm grasp on math and English, and a yearning to make it to college.

But despite her strong foundation, Bridget was drifting from school. As her fears grew and her mental health deteriorated in the wake of the Washington trip, Bridget’s grades slipped and her attendance faltered. She began seriously considering the prospect of going back to Ecuador. Even her eldest sister in their home city of Guayaquil — the one who initially encouraged her to come to the U.S. — had seen the news about Dylan. She urged Bridget and Marta to return.

ELLIS stepped up its support in response. Bernard connected Bridget with a therapist, helped her apply for housing, referred her to a lawyer to help with a court hearing coming up in late June and an ICE check-in a month later, and enrolled her in July classes to keep her engaged after the school year ended. But as a pivotal summer approached, he wasn’t sure it would be enough.

His work with Bridget felt like being caught in a riptide. “You can see the shore,” he said. But “you can’t move anywhere.”

Bridget and ELLIS Prep wrestle with doubts after Dylan’s arrest

When Bridget learned about Dylan’s arrest, she couldn’t stop picturing him in an orange jumpsuit with cuffs around his hands and feet. That was the uniform Bridget’s eldest sister had worn when she was detained by U.S. border agents a year earlier.

Bridget decided not to tell Marta that the lanky, purple-haired Venezuelan who’d made a point to shake her hand on a visit to ELLIS earlier that year was now in ICE detention.

“She would be very scared that they could deport us at any moment,” said Bridget, who, like her mother, asked to use a pseudonym, fearing immigration enforcement.

Bridget had tried for months to keep her own growing deportation fears at bay and stay strong for her mom. But after Dylan’s arrest, that grew harder. She started watching more TikTok videos about immigration raids and didn’t leave her midtown Manhattan shelter except for her trips to school and back.

ICE agents, facing pressure to meet stringent arrest quotas, had begun detaining immigrants after routine court dates and ICE check-ins, leading to a surge in arrests. Federal agents arrested roughly seven times as many immigrants in New York City during the first part of June compared to the same period last year. Nearly three-quarters of those arrests were of people who, like Dylan, had no criminal convictions or charges.

Bridget wasn’t the only one struggling to process the news about Dylan and the surge in immigration enforcement.

Students filled Bernard’s office to talk through questions about their immigration cases, and the stress crept into his home life. His own middle-school-aged children knew the details of Dylan’s case, and he often had to excuse himself from time with his family to take phone calls.

But the stakes felt too high to dial back his work. Normally, in the final month of school, students were worried about moving to the next grade or graduating. This year, he said they wondered: “Is a masked person going to grab me off the street?”

Vega mapped out the school’s response to Dylan’s arrest from her cavernous office adorned with student artwork and overlooking the school’s football field and the Harlem River.

As ICE shuttled Dylan from New Jersey, to Texas, to Louisiana, making it impossible for his lawyers to contact him, Vega grew angry.

“This situation makes it really, really real,” she told a room full of mostly quiet staffers during a meeting in a science classroom. “One of our kids was taken.”

The school helped launch a fundraiser that collected $43,000 for Dylan’s family, organized a schoolwide letter-writing campaign, and redoubled its efforts to connect students with lawyers.

As Dylan’s arrest sparked national headlines and local protests, even Mayor Eric Adams voiced his support, despite initially refraining from weighing in. The city’s Law Department filed a friend of the court brief in Dylan’s legal case, arguing ICE’s tactics would prevent undocumented New Yorkers from using city services.

In the days after Dylan’s arrest, Vega never wavered from the refrain she’d repeated since Trump took office in January.

“There’s nothing — nothing — that we are to say, or behave, that’s going to send a message other than: ‘You are going to college. You are going to graduate and have a future,’” she said at the staff meeting. “Our kids need to have a hope.”

In the weeks to come, though, Vega wrestled privately with her own doubts about whether the playbook she’d long relied on still worked. Many of her students went to private colleges in upstate New York because those schools had a relationship with ELLIS and offered significant scholarships. But ELLIS students were often among the few immigrants in their classes. Would that make them bigger targets for immigration enforcement?

And the Trump administration was trying to make it harder for undocumented students to access college at all. Trump issued an executive order seeking to curtail undocumented students’ access to in-state tuition at public colleges, a key benefit that allows some ELLIS students to pursue higher education.

Vega had always believed that a college education was the “great equalizer” for ELLIS students. “I feel like that comes into question right now,” Vega said in June. “Is it?”

Housing uncertainty and hardship lead to tough choices for an undocumented teen

On a Friday morning in late May, a week after Dylan’s arrest, Bernard got a call he’d been waiting weeks for. With Bridget and Marta’s permission, he had applied on Bridget’s behalf to a shelter for unaccompanied youth that could provide long-term housing along with extra support.

He knew stability was critical for Bridget. She had stayed in family and friends’ spare rooms in recent months and was tired of not having a place to call her own. Some nights, she curled up on the floor while her mom shared a bed with other relatives, sleeping only a few fitful hours.

Shortly after Bernard applied, Bridget and Marta were offered spots in a city-run homeless shelter in midtown Manhattan. It provided free food and privacy, but it was farther from ELLIS.

On the phone, Bernard learned the youth shelter had an open room and needed to hear back by noon that day. But Bridget would have to live apart from Marta.

For Bridget, the youth shelter’s offer was another reminder that her best chance at building a future in this country might require leaving her mom behind. Bridget had also applied, with the help of a lawyer recommended by Bernard, for Special Immigrant Juvenile status, a type of legal protection for youth abandoned or neglected by at least one parent. Bridget knew it was her best chance at legal protection, but it wouldn’t cover Marta.

Sitting in class that morning, Bridget could barely focus. She turned Bernard’s offer over in her head. In her English class, she stared at the pages of an autobiography she’d been working on for weeks.

On a page entitled “important people,” Bridget had written: “First my mom.” Marta had worked hard to make Bridget a “good person” and give her “a good future,” she wrote in neat handwriting.

Bridget turned down the spot in the youth shelter.

“Mama was alone. All she has is me,” she later said.

Whether they stayed in the U.S. or left, Marta and Bridget were going to do it together. Increasingly, they thought about returning to Ecuador.

Bridget missed her eldest sister, the smell of Ecuadorian street food, like caramelized apples, and sitting outside her house with her family, sipping on soda or juice as children played nearby.

On a warm morning in mid-June, as Bernard prepared for a meeting with parents to share legal resources, he got a WhatsApp message from Bridget that stopped him in his tracks.

“Mr Hedin good morning my mom is very frightened with everything and so am I,” she began. “To tell the truth I don’t feel good about all of this and we haven’t left the shelter at all, I know things are going to get worse and I think it would be best to go back to Ecuador.”

She asked if he knew how “voluntary removal” worked. For months, the Trump administration had been offering to pay for the flights of immigrants who agreed to “self-deport.” But few ELLIS families knew the details of the offer, or trusted the Trump administration enough to take them up on it, Bernard said.

Bernard quickly sent Bridget a voice memo asking her not to “make any decisions before talking to me.”

When they met in person the next day, Bernard urged her to stay in school while her legal case played out. Her court hearing was in a few weeks, on June 25, and the ICE check-in was about a month later.

He encouraged her to come to July classes to keep up her connection with ELLIS and prepare for the English Language Arts Regents exam next year. The school had placed her in an advanced English course starting in the fall.

Bridget reluctantly agreed. She still wanted to leave, but it was logistically complicated. She and Marta didn’t have the money for plane tickets, which would cost upwards of $1,000. It would also take time to arrange travel.

And anyway, Bridget had started helping Marta collect bottles and occasionally clean apartments. Even though their daily earnings were meager, it was far more than they could make in Ecuador.

Bernard had bought some time, but he wasn’t sure how much.

ELLIS’ mission put to the test under Trump’s policies

As ELLIS’ staffers entered the summer, they faced two challenges: keeping up a connection with current students and figuring out how the school would need to adapt over the year ahead.

ELLIS expanded its summer school last year to keep students engaged and on track to graduate. But the accelerating mass deportation campaign had made that more difficult, and it showed no signs of abating.

At the start of the summer, Congress approved a spending bill that set aside an unprecedented $170 billion for immigration enforcement. When an undocumented migrant shot a border agent in a Manhattan park just across the river from ELLIS, Border Czar Tom Homan promised to “flood the zone” with ICE agents, and Attorney General Pam Bondi sued the city over its “sanctuary” policies limiting local law enforcement’s cooperation with ICE.

On the last day of the school year, Bernard got a call from another first-year student and friend of Bridget’s: Her mom had been detained by ICE. The girl was devastated. With the arrest, she’d also lost the primary source of child care for her own toddler and the household’s main wage earner. She told the school she wouldn’t be able to make it to summer school.

Vega offered to take care of the student’s son in the principal’s office while she attended class. But the student never took her up on it, opting to work instead.

ELLIS has always had students balancing work and school. But some staffers saw the pressure to work growing — and starting earlier than usual — as deportation fears mounted.

“They feel the urgency to make money now,” said Maciel Lantigua, an ELLIS alumna and social worker for the Mission Society, a nonprofit that operates out of ELLIS, providing students with extra resources and support. “They don’t have the luxury of that time.”

Vega worried about hanging on to existing students. She was also stressed about recruiting new ones.

As a result of Trump’s policies, the number of immigrants unlawfully crossing the U.S.-Mexico border sank to the lowest point in decades in July. The rate of new migrants entering New York City shelters, meanwhile, had dropped to fewer than 100 per week from a high of more than 4,000 weekly two years earlier.

ELLIS staffers noticed only a handful of new students registering through the end of July, compared with 20-30 over the same period last year.

The slowdown forced Vega to consider whether the 275-student school would need to adjust its policy of only enrolling students over 16 who have been in the country less than a year.

At the same time, the Trump administration ramped up its efforts to cut off undocumented students’ access to public education.

In July, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced that undocumented preschoolers would no longer qualify for Head Start, a federally funded free child care program. Older undocumented students lost access to federally funded dual-enrollment, career and technical education, and adult education programs. Later that month, the Department of Education launched a civil rights investigation into universities providing financial aid to undocumented students who arrived as young children in the U.S. and have temporary legal protection, commonly known as Dreamers.

“The way this second Trump administration is targeting every aspect of life for immigrants makes students’ ability to access education that much harder,” said Alejandra Vázquez Baur, a fellow at the left-leaning Century Foundation and founder of the National Newcomer Network. “For that reason, it might be the most intense attack on immigrant students to date.”

At ELLIS, Vega has been raising money from outside donors for years to help subsidize undocumented students’ college costs. The school raised a record, over $40,000, this year.

And while Vega is committed to keeping students at ELLIS for four years, she knows the school will have to be nimble about developing flexible schedules for students feeling pressure to earn money right away.

She’s hopeful that the tides will eventually turn.

As Americans have started to see the effects of the administration’s aggressive enforcement campaign, the anti-immigrant sentiment that helped propel Trump into office has begun to reverse. The percentage of Americans who support curbing immigration dropped from 55% in July 2024 to just 30% a year later, according to a poll from Gallup.

That’s why Vega is confident that if she can make it through a few years of lean enrollment, the school’s situation will improve.

“The goal is to survive,” she said. “To still be here post-Trump.”

Can Bridget hold on to her education dreams?

Bridget and Marta, who were still terrified of being detained by federal immigration agents, had one stroke of good luck: Their June 25 court hearing was virtual.

In the weeks leading up to the proceeding, the pair found a pro bono lawyer to help them submit applications for asylum and for Bridget’s special juvenile status. The judge scheduled another hearing for 2027 while their claims wound their way through the slow-moving courts.

But they still had their in-person ICE check-in on July 21. Bridget, who had been watching videos about immigration enforcement, knew ICE agents were increasingly using the check-ins to detain migrants.

The night before the appointment, Marta and Bridget barely slept. At the subway station, Marta didn’t have enough money to buy her own one-trip pass and slipped through the turnstile with Bridget when she tapped her student OMNY card — knowing full well that getting caught could have devastating consequences.

On the train, Bridget, wearing a matching set of pink pants and shirt with the logo from the Nickelodeon kids show “Rugrats,” carried the immigration papers in crisp folders and stared ahead.

Dressed in a white and blue floral dress, Marta thumbed the small brown stuffed mouse named Mickey, who had traveled with her from Ecuador, attached by keychain to her fanny pack.

She played the possibilities and questions over in her head. Should she have brought a suitcase with her in case she was deported? Would she be separated from Bridget if they were detained? Would they send her back to Ecuador, or to a country she’d never set foot in?

A couple of weeks earlier, she’d found a stuffed pink rabbit on the street, and she clipped it next to Mickey on her keychain.

“If we get out of this, I’ll give it a name,” she said.

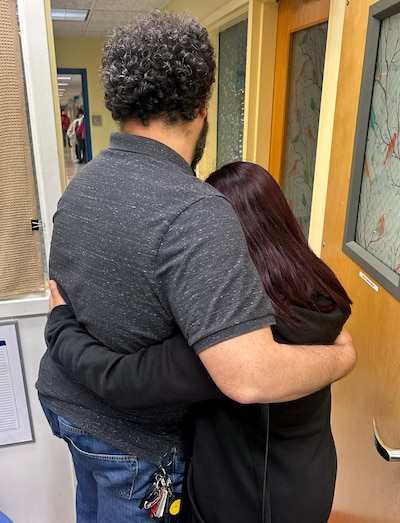

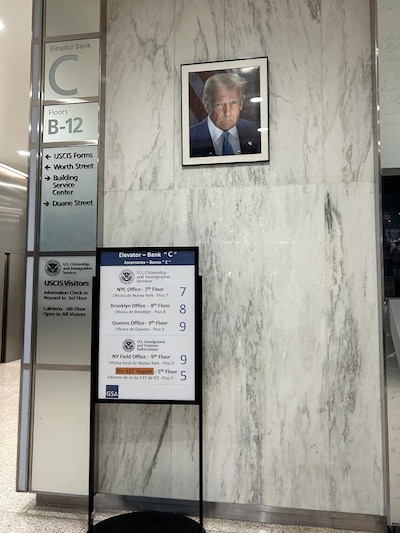

A snaking line wound its way inside to the first checkpoint at 26 Federal Plaza, an imposing steel and glass federal immigration building. On the courthouse wall, looking down on them, was a stern-faced portrait of Trump. Marta leaned her head on Bridget’s shoulder, and Bridget wrapped her arm around her mom.

Bridget and Marta — who still had a shared immigration case because Bridget entered the country as a minor — were referred to a room on the fifth floor for family cases. Five floors above them, dozens of recently detained migrants were being held in a makeshift detention center, forced to use the toilet in public and sleep on the floor with only thin blankets.

Two hours later, Marta and Bridget emerged, wearing faint smiles and clutching paperwork that listed the date of their next ICE check-in: exactly a year later.

Outside the building, with the sun shining, Bridget and Marta made a video call to Bridget’s eldest sister in Ecuador, who had been waiting for news. Marta christened the stuffed rabbit on her fanny pack “Pinky.”

The women were relieved, but they didn’t feel like celebrating. Marta wanted a coffee, but had no money to buy one.

Bridget’s dream of becoming the first person in her family to attend college for the moment felt a little more within reach — at least until her next court date. She still thought often about her friend Dylan, who remains in detention in Western Pennsylvania.

ELLIS staffers also hadn’t given up trying to reel Bridget in.

One morning in late July, Lantigua, the social worker, spotted Bridget and Marta near the school with a shopping cart full of cans and bottles. Bridget had for weeks been helping Marta collect them in the punishing heat. Lantigua invited Bridget to go see “Superman,” one of a series of activities she’d organized for students to keep them connected to ELLIS over the summer.

Bridget didn’t go. But Lantigua tried again with a trip on Wednesday to the New York Botanical Garden. She attempted a move that had worked in the past: inviting Bridget and Marta, too.

This time, they both showed up.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org