This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Pew Charitable Trusts has released a study showing that pension costs for the Philadelphia School District have increased nearly sixfold in less than a decade, from $28 million in 2010 to $154 million, significantly adding to the District’s financial woes.

The District’s payments into the plan, once they were offset by partial state reimbursements, now account for 15% of its payroll costs and 5% of its total budget.

School District payments to the state pension system, known as the Public School Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS), are mandated under state law. And the amounts needed to keep the fund solvent are affected by economic conditions and legislative decisions.

The high payments, the report said, are “making up for years of low funding levels, investment returns that failed to meet expectations, and unfunded benefit increases.” Due to the higher payments, the system is “on a path to improved funding, but the district faces some tough budget decisions as a result.”

In the report, which focused on Philadelphia, District Chief Financial Officer Uri Monson said: “Pension costs affect every investment we make, and the vast majority of the investments you want to make are in people.” Each hiring decision, he said, “is that much more expensive.”

Although costs will continue to rise over the next several years, the rate of increase is expected to slow considerably.

For public school employees, the state and school districts both put money into the fund at about a 1:1 ratio, and the amount of a school district’s contribution is determined by state laws as a factor of each employee’s salary. The money in each fund is managed by the state, and their performance and investment portfolios are available to the public.

Between 2002 and 2003, pension debt started to become positive. Pension debt is the difference between the amount that would be needed to cover all of the pension payments and the current value of the pension fund.

Pension debt is reasonably stable when it reaches $0, meaning that the plan is able to cover all future expenses. The amount in the pension fund can withstand some fluctuations. It is not a crisis to build up some pension debt, but too much could become a problem. Pension debt for the PSERS rose to more than $40 billion by 2016.

The author of the report, Seth Budick, said, “The pension system does not have the funds on hand to cover all of the future payments as of now, but that situation is changing.” It is changing because of major adjustments in the last few years at the state level to require school districts to make higher payments to the pension plan.

In 2000, the ratio of assets to liabilities was greater than 100%, so the pension was reasonably secure. Because there was so much money, the state legislature decided to alter the plan and allow school employees to take more out of the system.

They passed Act 9 in 2001, which increased pension benefits for PSERS beneficiaries retroactively. It states: “The increase in benefits for state and school employees provided herein will in effect allow them for the first time to share in the outstanding investment performance of the funds.”

But that “outstanding performance” would not last for long. The dot.com bubble burst, and then the Great Recession hit, decreasing the value of the pension plan by billions of dollars.

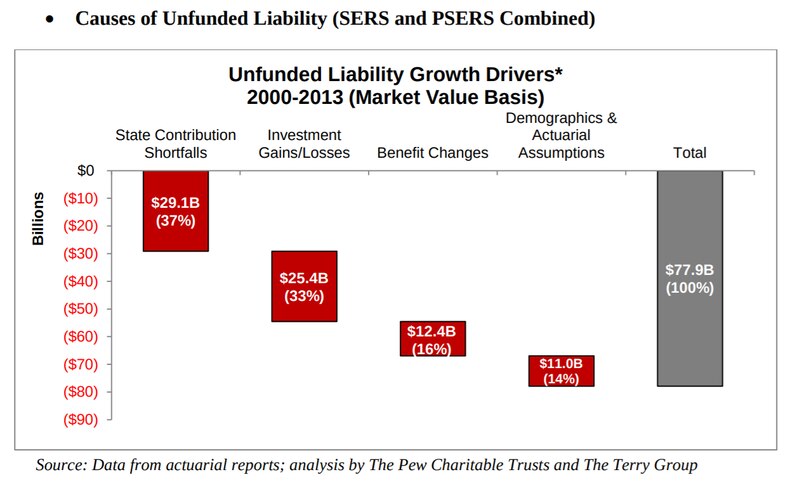

In 2015, Greg Mennis from Pew Charitable Trusts testified before the Pennsylvania Senate Finance Committee, saying: “Our research indicates that lower than expected investment returns account for about $25 billion of the increase in unfunded liabilities between 2000 and 2013.”

Mennis also said that funding shortfalls and unfunded benefits had been two other causes for the rapidly increasingly pension debt. “We estimate that these two factors – which reflected choices made by policymakers – account for more than half and approximately $41 billion of the recent increase in the state’s pension debt,” he said.

The graph below was provided with his public testimony, and it shows the four causes of unfunded liability or pension debt.

In the midst of the Great Recession, the state legislature had to act to maintain the security of the pension fund. Between 2005 and 2011, school districts across the Commonwealth were only making 20%-40% of the necessary payments, and the pension debt increased dramatically.

In light of this problem, Pennsylvania legislators passed Act 120 in 2010, which reduced pension benefits for newly hired employees. As is evident from the graph, payments into the plan also started to increase significantly.

Additionally, in July 2019, the state restructured the pension plans for new employees “with a view towards lowering costs and reducing risks,” according to the report. Under the new structure, employees choose between three different plan options.

“The school district’s pension payments are at historically high levels now, exerting a large impact on the overall budget for the school district and are projected to continue to increase gradually in coming years,” said Budick.

The School District addressed the issue of pension payments in its 2018-2019 budget (page 27), calling it “a major cost driver” and saying “retirement contributions are a State-mandated expenditure over which the School District has no control. The employer contribution rate for PSERS, which is set forth in State law, has been growing drastically in recent years, causing a drain on District resources.”