This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Board of Education unanimously decided Thursday to defer “indefinitely” a vote on an amendment allowing Laboratory Charter to consolidate its three campuses at a site in East Falls that once housed the Medical College of Pennsylvania.

The vote was taken after board members were told by residents and others that the move could adversely impact the neighborhood elementary school, Mifflin, and clog the neighborhood with school-bus traffic. They also said that Lab Charter and the District gave the community no notice of the proposed relocation.

“My primary concern is the lack of Laboratory Charter’s outreach prior to this vote,” said resident Carla Lewandowski. “To put it simply, there was none. … We feel this lack of engagement should disqualify them from being voted upon, as this is a major component of any school’s move to a community.”

Lewandowski, a leader in the Friends of Mifflin and mother of two children at the school, said she found out about the plans on April 11 from a Facebook post by a parent who happened to attend a meeting of a board committee at which the amendment was discussed.

The board’s Charter Schools Office (CSO) had recommended that the move be approved in part because it could improve the school’s financial position. Lewandowski said the board should take a bigger-picture view in making such decisions.

“Shouldn’t your decision be based on more than just whether or not a building has the space and whether or not a charter school’s financial standing will be made better?” she asked.

After the speakers and before the vote, Board President Joyce Wilkerson read a prepared statement echoing that viewpoint, announcing that the board would vote on a resolution to postpone the decision.

In reviewing the report from the charter school office, she said, “it’s clear that not enough thought was given to how this school will work for the community in which it is intended to locate. We cannot look at each decision in isolation.”

In addition, she said, “we will be revisiting the community strategies we use.”

The building to which Lab Charter was slated to move is due to be vacated by another charter school, Eastern Academy – although it doesn’t yet have a new home. Eastern remains in operation while it appeals a closure vote from the former School Reform Commission.

The same complex is also the site for a new charter school that was given final approval last night, Hebrew Public, which has an eventual capacity of 700 students.

Between Lab Charter and Hebrew Public, the potential exists for 1,700 K-8 students at the site, which is at 3300 Henry Ave.

Eastern has 350 students, most of whom are in high school and use SEPTA to get to school. Many of the younger students who would attend Hebrew Public and Lab Charter would be transported by school bus.

The sprawling site “has one main entrance to accommodate 1,700 students and their parents, and already houses several health facilities, without any clear discussion of whether or not the infrastructure can handle almost 1,400 more students on a daily basis,” said Lewandowski. “I can guarantee you that the School District will be dealing with serious traffic and safety issues if this move is approved, not least of which is the fact that current students will need to be bused more than half an hour along City Line Avenue.”

Mary Alice Duff spoke of the impact on Mifflin, which is working to attract more students from its immediate neighborhood. Although East Falls is more than half white and relatively affluent, the student body of Mifflin is mostly black and low-income, drawing students from a nearby public housing project, Abbottsford Homes.

“Mifflin is in every sense of the word, a community,” said Duff. “While I’m sure it’s not Laboratory Charter School’s intent to disrupt our local public neighborhood school, we have to ask ourselves what kind of message it sends to our public school students and the East Falls community when multiple charter schools, serving 1,700 students in the same grades, are approved to open in the same zip code, while an incredible neighborhood public school stands ready to educate more students.”

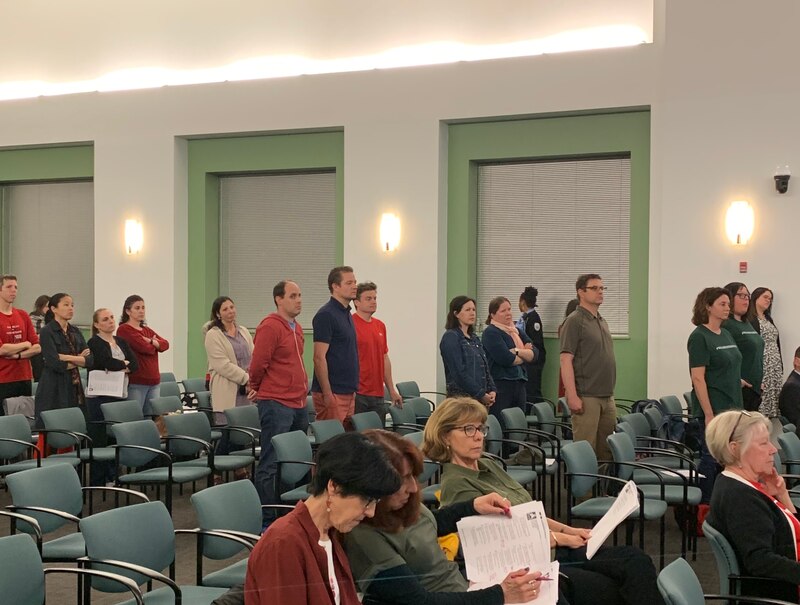

A contingent of East Falls residents and activists attended the meeting. They expressed satisfaction and relief at the decision.

They had gone door-to-door in the neighborhood, started an online petition that got more than 630 signatures, and reached out to the media.

Lab Charter, which was founded in 1997, was recommended for nonrenewal in 2017 due to financial and operational problems, but the School Reform Commission (SRC) ultimately extended its charter.

After the meeting, Wilkerson said that the board and staff would review the neighborhood’s concerns “and make a decision whether we want to consider the amendment.”

Under the charter law, the District is not obligated to consider amendments to charter agreements at all, but the SRC passed a policy, called Policy 406, to accommodate charters mid-term when they wanted to expand their enrollments or change location. Charters are usually renewed for five-year terms.

“We will be engaging the community, gathering additional information,” she said, adding that the board would keep the public informed. A determination will be made quickly, likely before its next meeting, because Lab Charter will have decisions to make if the consolidation is not approved. Two of its three campuses are in West Philadelphia and one is in Northern Liberties.

More than just the charter office will be doing the investigating and outreach, Wilkerson said, saying the District needs to find a more unified approach to making decisions regarding charter expansion.

“When the board says it is operating one system of public education, that makes it challenging because the Charter School Office is attending to charter issues,” she said. “We have to reach across and make sure we get District input, because it matters what happens to Mifflin, it matters what the impact is on surrounding schools, and I think that’s one reason we ended up in the situation we’re in because to some extent we’re operating in silos.”

A five-plus hour meeting

The meeting was a marathon, lasting five hours and 15 minutes with 76 speakers on the agenda, many left over from the March 28 meeting that was cut short when the board adjourned to a private room after a raucous protest by members of the Philadelphia Student Union against its vote to mandate metal detectors in all high schools.

Before hearing the speakers, Wilkerson made it clear that the board wanted to hear dissenting views, but that the public must maintain respect and decorum at meetings.

“We will not tolerate disruptions,” she said, but would “respect different points of view expressed in a safe environment.”

She also said that the board had reached out to the protesters and that the book isn’t closed yet on the metal-detector policy.

The board’s other controversial vote involved a $114,500 contract for Relay Graduate School of Education to provide professional development to five District principals. The measure failed, 5-4, after a discussion of Relay’s methods and effectiveness.

Board member Christopher McGinley, who has previously worked as a school principal and a suburban superintendent, said that $114,500 “for training a small number of people is an awful lot of money to spend with this organization.” McGinley, who now teaches at Temple’s Graduate School of Education, said he is not a fan of Relay’s methods or approach, saying that the “foundational” skills it emphasizes are ones that “principals should have before they are hired.”

Despite its name, Relay is not accredited as a graduate school of education in Pennsylvania, although it is in New York. It was founded by several charter schools to train their educators.

Chief Schools Officer Shawn Bird explained that the principals, all in the District’s Accelerated Network of second-chance alternative schools, would not be getting graduate credits for the training. “It is professional development,” he said.

Board member Angela McIver, who helps teachers with math instruction, pushed back against McGinley’s view. “I think it is problematic to assume that an accredited program is training teachers and principals in a way that makes them effective in the classroom,” she said.

McGinley said he thought there were other, better programs out there for the money.

This strand of leadership training started with a grant from the Philadelphia School Partnership, but it is now paid for with federal Title I funds. In any case, Bird said, starting next year, the intent is to bring all such training in-house instead of relying on outside vendors. “This is the last group of principals for which we are relying on a contract,” he said.

Parents from overcrowded schools in South Philadelphia stand as Craig Morton speaks at the April 25 school board meeting.

About 20 parents from Meredith and Nebinger Elementary Schools in South Philadelphia waited for five hours to talk about solutions to the overcrowding in both schools. The crowding has been the result of an increasing population of young families in the area and a renewed commitment to using District schools. The result has been classes of 35 students or more. In some cases, younger siblings are unable to get into the same school as their older siblings and are put on waitlists.

“A number of schools are facing this issue,” said Meredith parent Craig Morton, whose younger child is on a waitlist. “This board is going to hear more and more about this.”

Children on waitlists for their neighborhood school are sent to other schools that have room.

Superintendent William Hite said that he realizes a broader strategy is necessary. “We are looking at this issue extensively to make short- and long-term recommendations [and to see] what options we have in the long term, including capital investments.”