Sharon Brewer is getting the chance to spend at least some of her senior year in school, in person.

It didn’t come a moment too soon.

“I was doing terrible at home,” she said.

Same for her classmate, Parris Boyette.

“It’s the best thing that happened to me,” said Boyette, a 17-year-old basketball player, about returning to school in person last month. “My grades are going up, I’m understanding more. When I was home, I was not paying attention. Here, I’m paying attention.”

The two are students at Mastery Charter School-Pickett Campus in Germantown, a combined middle and high school with grades 6-12 that reopened for in-person school more than a month ago.

Unlike the Philadelphia school district, which won’t bring back 10th to 12th graders this school year, Mastery has tried to bring back as many students as possible in all grades in its 18 schools across the city. The charter network, which enrolls about 14,000 students, started hybrid learning back in March, with some starting in April, and has moved its students phase-in at a faster pace than the district.

Most students are back two days a week, except for those with special needs, who can come in four days.

“It is indisputable that in-person learning is what’s best for students,” said Mastery CEO Scott Gordon. Its internal assessments indicated that students learning at home were attaining less academic growth than in a typical year, he said. At the same time, he said, they were also showing “greater levels of depression and anxiety” as levels of gun violence hit historically high levels.

As a result, “we made it an absolute priority” to maximize in-person learning, including for older students, he said.

While the district also sought an early and fuller return to school buildings, it was a rougher road, exacerbated by deep distrust over dangerous building conditions. After a protracted dispute with the teachers union over school safety that was finally settled through mediation, the district has brought back students in phases. Students in prekindergarten to second grade began hybrid learning in three waves in March, followed by students in third to fifth grade this week. By May 10, sixth through ninth graders can begin in-person learning, most for two days a week. The school year ends on June 11, meaning the last eligible students will have just 10 days of in-person learning.

Most high school students won’t be back this school year.

“We’ve said this before, we understand this is not the school year any of us have envisioned,” said Monica Lewis, the district’s spokeswoman. “Those in high school, particularly seniors, are probably disappointed. They have missed out engaging with friends and doing activities typical of high school life. But this was the plan most in line with efforts to get through the pandemic as safely as possible for all students and staff and school communities as well.”

To help students who might have fallen behind, the district is beefing up its summer offerings, providing credit recovery courses, and encouraging families “to reach out to school to see what services are available,” she said.

Keylisha Diaz, one of two student representatives on the Board of Education and a junior at Philadelphia Military Academy, a district school, has been keeping in regular touch with seniors and other high school students advocating for their needs. Seeing the process up close, she said she has developed a keen appreciation for the hard choices faced by the district’s leadership.

At the same time, she said, “It’s very upsetting seniors didn’t get the experience they were hoping for.” At this point, however, given how late it is in the school year, most of those she has spoken to have made their peace and “are fine with staying virtual.”

Instead, she said what they are looking forward to are the end-of-year rituals, especially graduations, which the district has said will be held outside. It is also providing free caps and gowns to students. Proms, however, will not be held.

Two different approaches

Like the district, Mastery has paid close attention to the guidance from federal and state health agencies. But the charter network has been determined to bring students back since the start of the year.

Mastery held outreach sessions for parents in the summer, and then opened school buildings for a short time in September. Schools closed again when there was a surge in coronavirus cases in November and stayed closed for the rest of the winter. A phased reopening began in early March, with all students who wanted to return coming back for some in-person learning by the end of April.

Across the country, many school districts have focused first on reopening buildings to younger students and those in special education classes. High school reopening also has been a challenge because older students change classes more often, making it difficult to create socially distanced pods.

Like the school district, Mastery has faced challenges with social distancing and classroom capacity. Almost all their schools are converted district schools ceded in the hopes of rapid academic turnaround, so they have many of the same challenges with old and poorly ventilated buildings.

But Mastery hasn’t faced bitter pushback about safety. The network spent $4 million on upgrading ventilation, including the purchase of expensive air purifiers, and $2.5 million on COVID-19 preventative measures like frequent student and staff testing, said Gordon. It tests weekly, using less expensive batch tests for 20 people at a time; if there is a positive reaction the source can be traced to one or two participants who can then be retested individually.

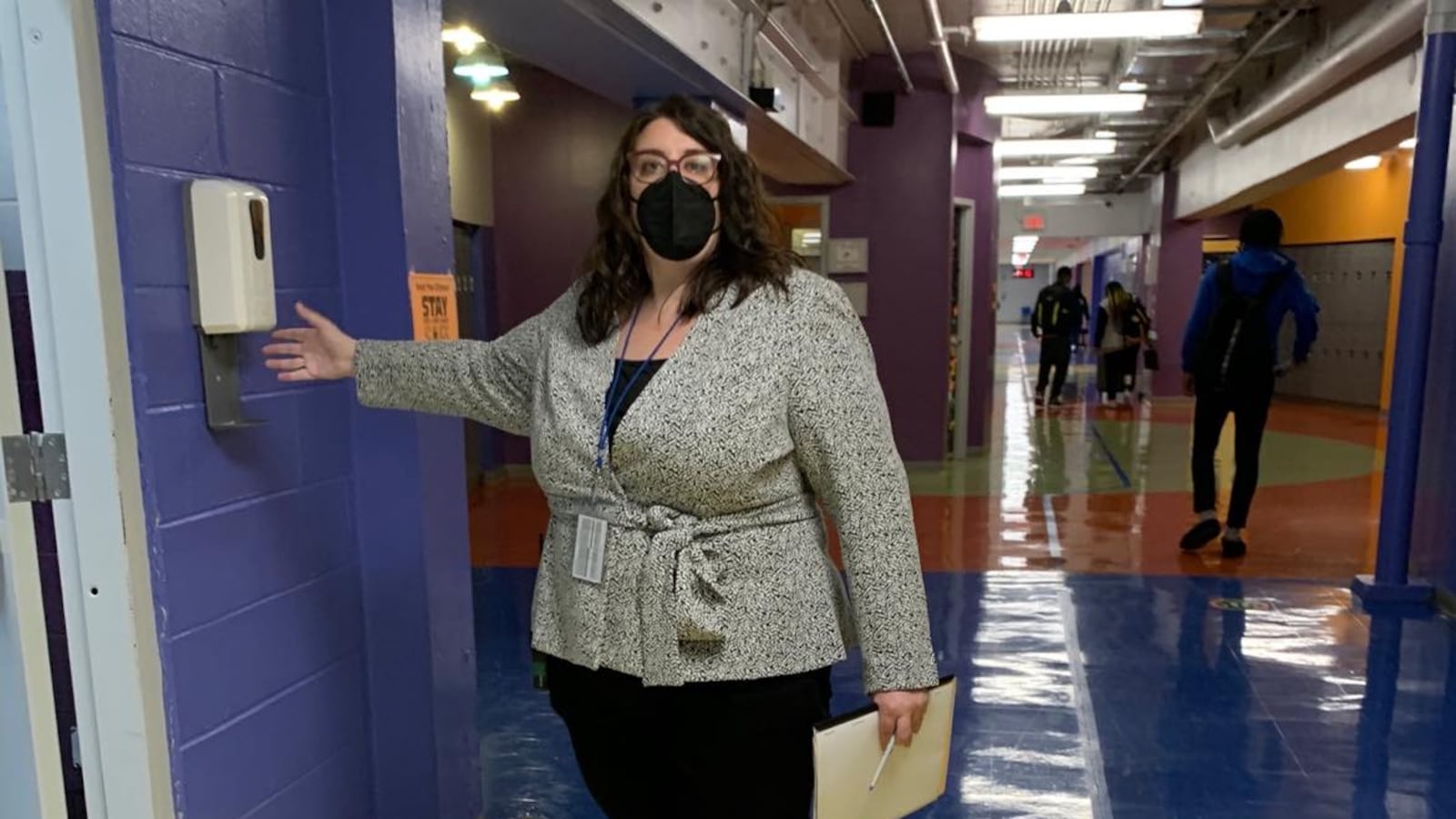

The network also conducts careful contact tracing. People entering the building can scan their phone in front of one device so they can be notified if someone else in the school that day tests positive. They step in front of another device to have their temperature taken. Mastery maintains a dashboard of positive test results, and it says there were 63 cases this week and 306 since testing began. Pickett has had eight positive cases, according to the dashboard.

Mastery spokeswoman Kerry Woodward said that since reopening it has had one classroom quarantine and two schools have “paused” in-person instruction due to an uptick in COVID-19 cases; Wister is closed until May 3 and Clymer until May 5.

The school district started a dashboard after pressure from the The Caucus of Working Educators and Parents United for Public Schools, activist groups that were seeking more transparency and had begun tracking positive COVID-19 cases on their own.

Like most charters, Mastery doesn’t have a teachers union, but it still faced questions from teachers and students about whether it was safe to be in buildings. Gordon said that he and his team maintained constant communication with its teachers and the network’s 11,000 families.

“We had open town meetings, and lots of meetings to get staff comfortable,” Gordon said. “When we have an infection, we respond quickly. We built confidence we could manage through this.”

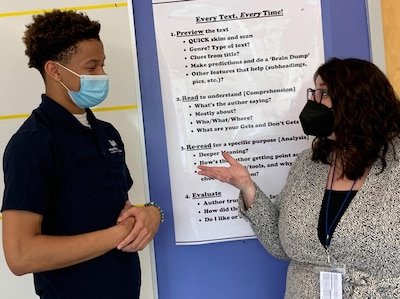

Sam Scarpone, an English teacher at Pickett, said at first she was apprehensive about returning, mostly when teachers were not being prioritized for vaccinations and due to “fear of the unknown.” Once she set foot in the building, she said, “all my fears dissipated.”

While it varies by school, just under half of Mastery’s students have elected to come back to the hybrid model, Gordon said. At district schools, the figure has been closer to one third of those eligible at any given time.

Neither the school district nor Mastery could offer exact numbers on how many high school students are on track to graduate now compared to the norm in other years, although Mastery said it has not detected a dip.

‘It’s not natural for them to be so isolated’

At Pickett, Principal Margaux Munnelly said that returning to in-person school has major benefits: increased engagement with learning, lessening of distractions, more interaction with teachers, and the opportunity to socialize with friends.

“You want to see your students learn and grow and thrive,” she said. “Welcoming our students back into our building over the last several months has been a joy. I could not overstate the importance of the connections I am seeing our students make with our teachers and with each other.”

Both Scarpone and Katy Kahn, who teaches Advanced Placement and honors literature classes, said they want to see more students in the building. They feel the benefits far outweigh the risks.

“I want as many kids back as possible,” Kahn said. “I’m also planning summer camp. I’m anxious about getting kids up and out for academic and social purposes. The kids need it. It’s not natural for them to be so isolated.”

In fact, after the initial wave in March, more students did decide to come back to Pickett, which enrolls more than 900 students. Just over 300 students returned in March and another 200 returned this week at the start of the fourth and final marking period — meaning about half the 917 students have chosen to return.

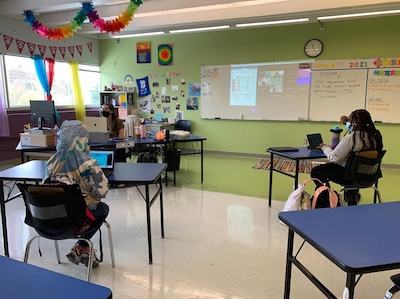

To be sure, with maybe a quarter of students there at any given time, the vibe in the school is still nowhere near normal, although some classrooms now have 10 to 12 students in them, spaced out and working on laptops behind plastic barriers. During lunch, there is one student per table, and everyone faces the same way. Hallways are still eerily quiet during class changes.

For seniors like Brewer, however, returning has been a lifesaver. For most of the year, she worried she wouldn’t be able to graduate because her grades plummeted. While some students, she said, were excelling at home, she struggled.

“I am a social person, I need to be in class writing, taking notes, and listening to my teacher talk. I need to be physically participating. I need to ask questions, I can’t sit around and wait for a breakout room,” she said.

Since she came back to school in person, “I feel like I’m improving already. I get more work done. I’m more verbal. The best part of being back here is I’m able to get to the grade-point-average I’m used to.”

Boyette is also happy to be back. He also said being at home all the time was too distracting. “I just want to be with my friends,” he said.

School is better, he said, but in many ways “it feels weird. You can’t walk around like you used to, you’ve got to stay away from other kids.” So, like Brewer, he studies and buckles down on his work. Unlike at home, he pointed out, where the TV, smartphone and refrigerator beckons, “There is nothing else to do here.”

Munnelly, the principal, had to agree. “It’s not the same. But it’s something.”