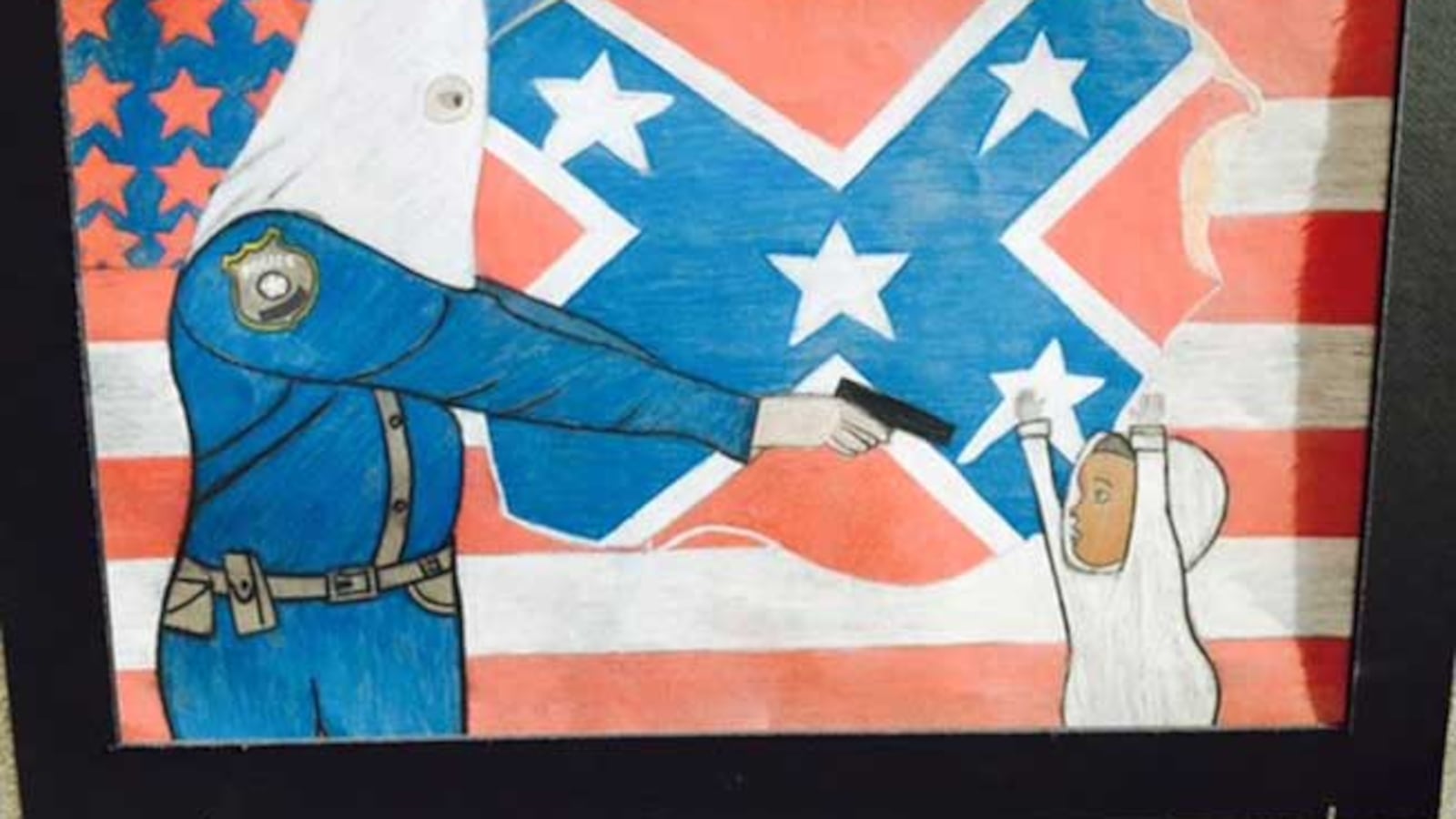

The controversy that led a Denver tenth-grader to request her drawing of a police officer in a KKK hood pointing a gun at a child of color be removed this week from public display has raised several thorny but perennial questions: Should students be given full artistic freedom? Or are there limits?

And if a student creates something provocative, should it be displayed?

City and school district leaders touched on those topics at a news conference Friday after a private meeting between the student, a sophomore at Kunsmiller Creative Arts Academy; her parents; Denver Mayor Michael Hancock; Denver Police Chief Robert White; Denver Public Schools Acting Superintendent Susana Cordova and school principal Peter Castillo.

The meeting was organized after Denver police officers raised concerns about the art, which closely resembles the painting “A Tale of Two Hoodies” created by artist Michael D’Antuono after the 2012 shooting death of unarmed black teen Trayvon Martin. The Colorado chapter of the National Latino Peace Officers Association called the student’s piece “hate art.”

According to DPS, the student subsequently requested it be removed from the downtown Wellington Webb municipal building where it was displayed. She did not appear at the news conference, and officials said she didn’t want to speak with the press.

But White said that after talking with the teenager — whom Hancock called mature, confident and articulate — he’s sure she wasn’t intimidated into making that decision. He said she expressed in the meeting that she values the police but “there’s a lot of work to be done.”

White said he wasn’t offended by the artwork but was “greatly concerned.” Following several days of student walkouts in December 2014 in protest of police shootings in Ferguson, Missouri, and elsewhere, White met with DPS students to discuss their views and how to build a healthier relationship between Denver police and the city’s youth.

“The reality of it is there are a lot of people across this country and our community who still portray police officers that way,” he said. “And it is our responsibility to mitigate that portrayal. And that can only be done by having meetings like we had today with this young lady.”

Cordova said the conversation exemplified how art can open a dialogue.

“The idea is that it’s important for our students to understand that if you put a message out into the world, the world does respond,” she said.

Hancock said city officials “don’t want to censor or douse the spirit of the arts.”

“We want to continue to encourage our young people to do their art, to exhibit their art in city buildings,” he continued. “But we as adults have to make sure that we protect them and we make sure the message is honoring to the entire community.”

The student’s piece was part of the annual DPS High School Art Exhibition, which includes paintings, drawings, sculpture and jewelry by DPS students and chosen by a jury that includes community artists. It was hung in the high-ceilinged lobby of the downtown Webb building.

And it was not the only boundary-pushing piece. The show, which is on display through April 14, also features a drawing entitled “Anti-Immigration” that depicts a clawed animal with a face resembling Donald Trump chasing Speedy Gonzales through the desert. Another shows a nude figure holding a sign that says “God Hates Fags.” The word “My” has been scrawled above “God” and the word “Hates” has been crossed out and replaced with “Loves.”

Yet another piece has two sides: On one, police officers in black-and-white raise their batons against protesters. On the other, which is in color, white police officers in riot gear stare stony-faced at a black man, his mouth open as if he’s yelling. Its title? “History Repeats Itself.”

DPS doesn’t have a policy restricting the art students can create. Castillo, the Kunsmiller principal, said the school draws the line at vulgarity and profanity.

“Outside of that,” he said, “we embrace most of the creative process with artists.”

In a statement, DPS noted that depictions of weapons are usually prohibited from the High School Art Exhibition. An exception was made in this case, the district said, in part because “the piece was relevant to current events and important topics for students and our society.”

Connie Stewart, a former art teacher who is now an art education professor at the University of Northern Colorado, said teachers shouldn’t be afraid to let students express what’s on their minds. In 2001, shortly after 9/11, Stewart was teaching at an elementary school. She gave the kids rolls of butcher paper, played soft flute music and let them draw.

Their artwork ran the gamut, she said. “I had images of flowers and butterflies and some images of people falling out of windows,” Stewart said. “They needed that outlet.”

But there’s a difference between allowing students to create art that’s meaningful and tolerating art created just for shock value, Stewart and other current and former art teachers said. Educators should endeavor to distinguish between the two, they said.

“You have to, as a teacher, keep things in a context of, ‘Are you using your personal voice? Is this your experience, your truth?’” said Kendra Fleischman, a visual arts teacher at the public Denver School of the Arts who previously taught in Jefferson County.

“We do see quite a bit of artwork that deals with some pretty tough issues,” she said.

Jay Seller, who taught theater in Adams County for 32 years and is now executive director of the Denver-based Think 360 Arts for Learning, which provides professional development for arts teachers, said the topic of the Kunsmiller student’s piece doesn’t surprise him.

“In the context of Black Lives Matter and current events, it only appears appropriate that that student would feel those images depict the world around her,” he said. “You would never want to deny personal expression. The old saying, ‘Art imitates life’ — that is dead on.”

However, Seller and others said teachers should think carefully and use common sense to determine if and where to display potentially touchy student art.

“They need to consider the community and how the artwork will be viewed by their particular community, and whether or not the artwork would cause more damage than constructive comments,” said Pat Franklin, president of the National Art Education Association and a veteran art teacher and administrator in Virginia public schools.

Said Seller: “Hanging the art in the Webb building where law enforcement agents are going to walk by it and see the depiction? That’s probably pushing some buttons.”

But Fleischman said she thinks it’s unfortunate the piece was removed. “That’s concerning to me because it does send a message to students that, ‘Oh yeah, we want you to protest through your art but if it offends us, we’re still going to take it down,’” she said.

Stewart, who helps train future art teachers, acknowledged that situations such as this one are complex. She said she advises her students that one way to address controversial topics is to have kids respond to the “big ideas” behind them, such as safety, comfort and respect.

“Creativity is nurtured within limits, and every teacher decides what those limits are going to be,” she said, noting that teachers should make sure lessons are age-appropriate.

But she emphasizes that they shouldn’t necessarily shy away from uncomfortable subjects, or from questions that don’t have easy answers.

“My personal opinion is you take the risk,” she said, “because it’s more important for art to mean something than for it to mean nothing.”