As it faces possible state actions for failing to improve achievement and a divided community and staff, the Adams 14 school board must decide whether to authorize for the first time a charter school in its community.

The decision has provoked concerns among school board members, who have no experience reviewing and authorizing charter schools, and has divided parents and teachers just as they had started working together on other issues.

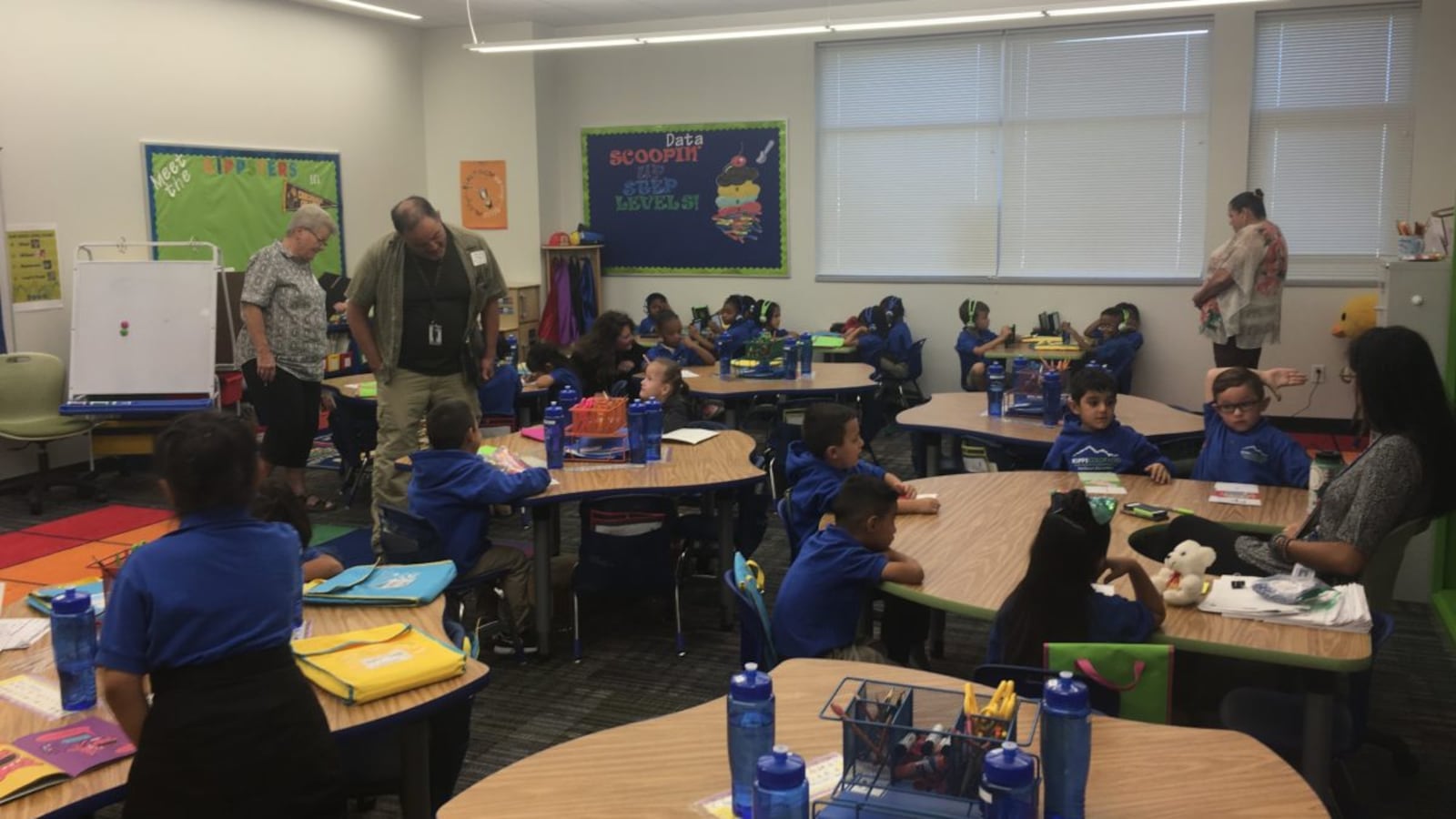

KIPP, the largest charter network in the country, wants to open a preschool-through-12th-grade campus that will offer biliteracy — a Spanish-English option that charter officials say parents requested after Adams 14 put the brakes on its biliteracy program.

After a monthslong review process created after KIPP submitted its charter application this summer, Superintendent Javier Abrego will issue his recommendation on Tuesday. The board will also hear a recommendation from a committee of parents and teachers that are proposing to reject KIPP — even though the group didn’t reach consensus.

Teacher Deborah Figueroa said she’s not impressed with KIPP’s academic plan, is concerned with the amount of testing the charter does, and questions the school’s knowledge of the community.

“They had claimed to be in touch with the community, but then submit an English-only application,” said Figueroa, a member of the District’s Accountability Advisory Committee that is recommending against KIPP. The district had to pay for translating the document into Spanish. “For an organization that has the money, I find that disrespectful to the district and the community.”

But other parents have been excited about a possible KIPP school in their community.

“Why not open opportunities for more schools of these types so that as parents we could be more certain that our children will achieve?” Patricia Bruno, a mom of four students, told the board recently.

After hearing recommendations Tuesday, the board will have a month before its final vote.

By Colorado law, the Adams 14 board must consider if the application is complete and sound, but may not deny it based on factors such as district finances or the existence of a similar model of school. If the board denies the application, KIPP may appeal to the State Board of Education which would consider if the decision was “contrary to best interests” of students and the community.

Adams 14’s academic standing adds another layer of complexity to the board’s decision. The vote is scheduled just days before the district is expected to present to the state board to explain its low performance. The district is already on a state-ordered plan for improvement, but has failed to show better results.

To avoid new state orders, the district would need to convince the state it’s doing everything possible to improve, and so the vote to approve or deny the high-performing charter could factor into those discussions.

Figueroa said she kept potential state action out of her mind when making a recommendation on KIPP.

“We weren’t thinking about the state, we were directed to make a recommendation based on the content of the application,” Figueroa said. “This whole concept of local control is still real as I understand our state.”

The KIPP application splintered a group of community organizations and the teachers union that had come together in the past year hoping to build a stronger voter base to help the struggling district change direction. As groups split over KIPP opening a school in the district, tensions rose and have erupted in confrontations in meetings and the district parking lot.

One district mom, who asked not to be identified out of fear of retribution, said she’s never seen such division in the community and said she feels teachers don’t understand parents’ urgency for better school options.

Ariel Smith, a founder of the Transforming Education Now, said the divisions have been disheartening and confusing for families. The parent advocacy nonprofit supports school choice and has been working with parents supporting KIPP.

“We’re just seeing parents be intimidated out of participation in a coordinated way that’s very concerning,” Smith said.

But Figueroa speculated the tensions had to do with money.

“It’s different this time,” Figueroa said. “It’s not about education.”

Despite the fact that the board can’t base its decision on KIPP’s impact on district finances, money has been a big question for the school board too. Brian Eschbacher, a consultant who volunteered to help the district, and its finance officer told the board Adams 14 could lose a lot of money to the charter school, but also noted that more than 3,000 district students are already enrolling in schools outside the district, meaning a loss of about $26 million in state funding. Eschbacher used to work for the Denver school district, where KIPP currently operates several schools.

Figueroa’s list of concerns with KIPP’s proposed plan include its biliteracy program. KIPP just started offering such a model this year at one of its schools in southwest Denver and would bring it to Adams 14.

“It’s the same exact thing Adams 14 has but they’ve never done it before so what makes us think it’s going to be better?” Figueroa said.

But the inclusion of the model in KIPP’s proposal has been a popular attraction for parents.

Board members have had a multitude of questions and several meetings to learn about the school’s application and the law, but still seem to wrestle with the same questions that make up the charter school debate nationwide, including how the charter will impact district finances, and specifics like how KIPP reports its finances or if it pays its board members. (It doesn’t.)

“Colorado as a pro-choice state has chosen to define and recognize charter schools as public schools but that doesn’t make them public,” board member Bill Hyde wrote in a blog last week, arguing that he doesn’t consider charter schools public, even if they legally are defined as such. “With privatization coupled with globalization, the public at large has lost sight of what constitutes a public entity.”

Board members have also questioned KIPP and district officials about the charter school’s education plan.

Connie Quintana, the board president, said at one meeting that she was especially concerned with the charter’s education of special education students. She wanted to ensure that if the school were to open, the option of attending was equal for all students.

The district has had its own struggles with special education at several schools.

Board member Harvest Thomas asked KIPP if any of its schools in Denver have been on turnaround, the state’s lowest quality rating for schools. Charter officials said that one school has, but after several changes the school’s ratings seem to have improved.

Adams 14 has had several schools with turnaround ratings in the past, but based on preliminary ratings, this year, for the first time, no schools are in that lowest category.

Many parents knew the district struggled, but the realities of how low the district’s achievement has been have only become clear recently as the state started to intervene.

At one community meeting specifically to discuss the KIPP application, a less common step in the review process, several moms said they went to learn if they could find a better school for their kids. Most walked away impressed with KIPP.

“We have really appreciated the community and the chance to meet with so many stakeholders,” Kimberlee Sia, KIPP’s executive director, said. “I do think it has really been an opportunity for us and the district to talk about KIPP.”

In August, the district signed a $90 per hour contract with a consultant to help create the review process that is being used. If the charter were approved, the contract also mentions the consultant could help the district prepare for the school’s first year.

Board member Hyde wrote online this week that he understands that parents have an urgency to find better schools, but he said there are opportunities coming up for the district to make improvements.

“These people’s request is not necessarily for KIPP, but for a better educational option for their children and right now KIPP is that more viable option,” Hyde wrote. “It should not be that way.”

This article has been corrected to reflect that Brian Eschbacher was not paid for his consulting services.