Four years and an entire chancellorship after Mayor Bill de Blasio promised to diversify New York City’s most elite high schools, the schools remain as stubbornly segregated as they were before he took office.

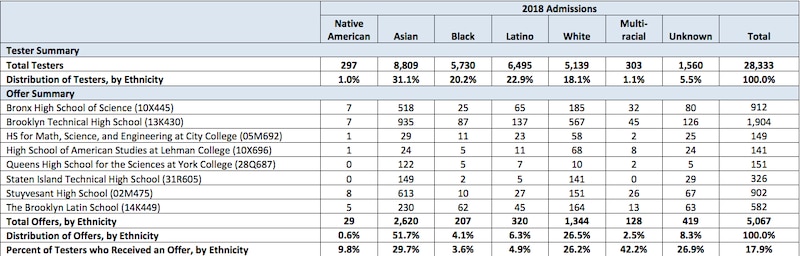

Only 4.1 percent of offers at the specialized high schools that require an entry exam went to black students, while 6.3 percent went to Hispanic students, according to data released Wednesday by the education department. Together, those students make up about 70 percent of city students.

The vast majority of eighth-graders who received admissions offers were white or Asian. More than 28,000 took the admissions test, and a total of 5,067 offers were made.

The picture is virtually unchanged from the previous year, before the city shifted the entrance exam to more closely reflect the skills it expects students to be learning in eighth grade. It was the latest effort to change an admissions equation that has been impermeable to change over the last two decades.

Students are admitted to eight of the specialized high schools based only on how well their results rank on the high-stakes Specialized High School Admissions Test. While those schools represent just a handful of New York City’s most prestigious high schools, their long history of serving top students — and the rapid decline of diversity at those schools — has put them at the center of a contentious debate about whether the city is doing enough to help black and Hispanic students succeed.

This year’s admissions data will surely fuel that debate. Just 10 black students were admitted to Stuyvesant High School, the most selective of the specialized schools, where a total of 902 students received offers. Staten Island Technical High School, the lone specialized school on Staten Island, admitted just five Hispanic students, in a class of 326.

Under de Blasio, the city has undertaken a number of initiatives to help students of color get admitted to the top schools, including administering the entry exam during the school day in districts where few students have qualified for admission, and offering test prep through its Dream program.

But advocates say little will change unless the city is willing to tackle the way students are admitted to specialized high schools, since middle-class families are still able to out-prepare their children for the exam. City officials contend that would require a change in state law — something advocates dispute, at least for five of the schools — and have appeared unwilling to lobby for any changes.

Lazar Treschan, who has studied the city’s specialized high schools closely for the Community Service Society of New York, has recommended tweaking admissions so that the top three percent of students at every middle school are offered admission. Doing so, he says, would double the number of black and Hispanic students at specialized high schools.

“The mayor has spent a lot of money on cosmetic, superficial things,” he said. “But we’ve come to a time where the numbers show they’ve done nothing.”

The city has defended its efforts and is expanding them. As proof Dream is working, the city highlights that students in the program comprised 8 percent of black and Hispanic test-takers but 29 percent of admissions offers. There are plans to double the number of seats in the test prep program to 1,600 in 2019. In addition, the city will increase the number of schools that offer the entry exam during the school day from 15 to 50.

In a statement, Chancellor Carmen Fariña said she was “excited for the tens of thousands of students across New York City who are set to begin a new part of their educational journey” and that she believes the city has made the stressful process easier to navigate.

“While we have made significant progress in helping students and families through the high school admissions process, we know there is a lot more work ahead in order to achieve excellence for all our students and schools,” Fariña said.

While the specialized high schools’ student populations are not set to change next year, at least one small-scale effort to boost economic diversity in city high schools seems to have paid off. Four of the five high schools in the city’s “Diversity in Admissions” pilot program met their goals — to increase the proportion of students from families whose incomes qualify them for free school lunches. Only Bard High School Early College Queens fell short — by one percentage point. Most of those schools had set out to serve diverse populations when they opened within the last decade but found themselves becoming more affluent and white over time.