A national pioneer in school turnaround work, Tennessee has launched a third model for improving struggling schools — based in part on lessons that have emerged from the state’s first two efforts over the past decade.

The new Partnership Network, now in its first year under a five-year agreement between the state and Hamilton County Schools, is focused on five schools in Chattanooga where student achievement has languished for decades.

The collaborative model takes a page from learnings garnered mostly in Memphis. The city is the hub of the state’s two other turnaround models, one of which involves wresting control of low-performing schools from the local district.

“I would describe this model not as a state takeover, but a state pushing” toward a different style of intervention, said state Education Commissioner Candice McQueen of the Partnership Network.

All three turnaround options are outlined in Tennessee’s plan under the new federal education law known as the Every Student Succeeds Act. The law requires each state to come up with a strategy for improving chronically underperforming schools.

Most promising so far has been Shelby County Schools’ Innovation Zone, a district-led program that provides struggling Memphis schools with extra state-funded resources and charter-like autonomy.

The other approach, the state-run Achievement School District, has been lackluster in performance and heavy-handed in its execution, but state officials are hopeful it’s a late bloomer, especially under the new leadership of the iZone’s former chief. Known as the ASD, the district has taken control of dozens of low-performing Memphis schools and matched them with charter operators.

State officials once had considered the cluster of Chattanooga schools for ASD takeover. But they came up with the partnership approach as a third way, wherein a seven-member advisory board named by both partners oversees the work of the mini-school district comprising 2,300 students.

One Chattanooga school was once a heralded example of successful turnaround. What happened?

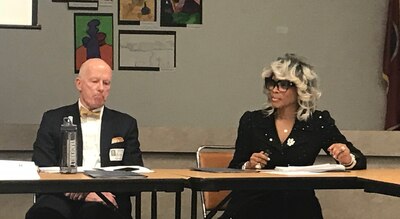

The partnership model, while unique in its structure, will only be as good as its outcomes, McQueen emphasized Monday during the advisory board’s second meeting.

Since embracing school improvement as part of a 2010 overhaul of K-12 public education, Tennessee has committed to a series of independent studies to track results with an eye toward data-driven refinements and new strategies. The research is the basis for a policy brief released this week outlining the state’s guiding principles for effective school turnaround. The Tennessee Education Research Alliance, a collaboration between Vanderbilt University and the state education department, developed the guidelines.

There is no magic bullet, said Gary T. Henry, the lead researcher behind the brief and a professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt.

He said the work of fixing struggling schools is “the most challenging work in public education today.” That’s because it really does take a village, he said, that includes the local school district, the state, federal dollars, and a sustained commitment from all parties to attack the problems from multiple angles.

In addition, there must be a willingness to treat low-performing schools as special cases that merit additional resources and higher pay for effective teachers and administrators — something that school districts are loathe to do and that defies political gravity, Henry said.

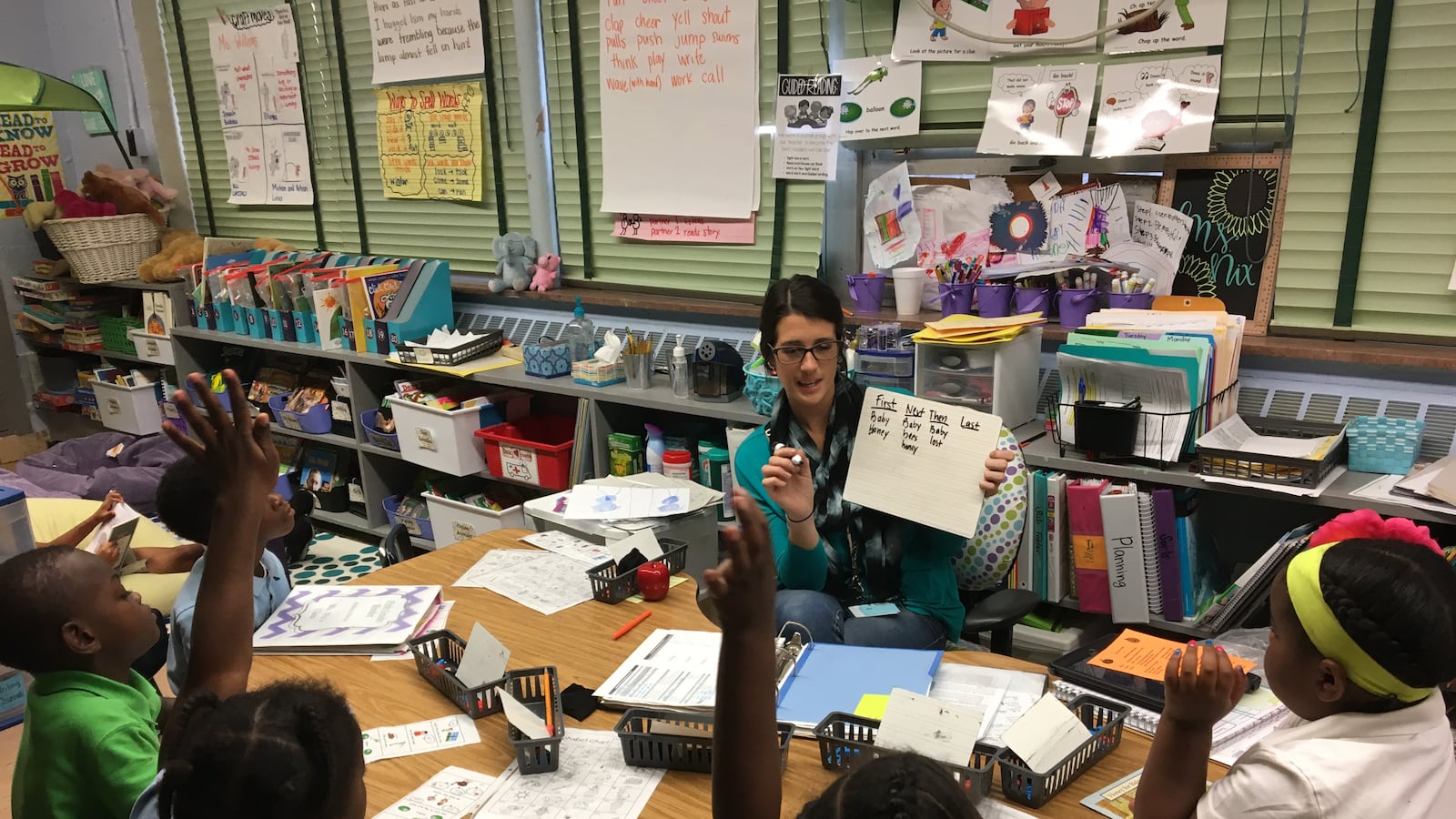

It also means building a district-within-a-district organizational structure dedicated to school improvement; removing barriers to improvement such as high teacher and leader turnover rates; increasing capacity for effective teaching and leadership with supports such as curriculum, training, and mentoring; and establishing school practices and processes — like opportunities for teacher collaboration — that promote continuity and stability.

“Doing one or two of these will not necessarily change the lives of students and teachers and principals. But doing all five intelligently and in focused fashion can,” Henry said.

The work must recognize, too, the profound impact of poverty on the students who generally attend low-performing schools, said Sharon Griffin, the former iZone chief hired last spring to run the state-run ASD.

“Sometimes just showing up (to school) is a miracle,” Griffin said of kids who bring adverse and chronically stressful experiences into schools and classrooms.

A nationally recognized turnaround leader, Griffin told the new Chattanooga advisory board about the improvement work she has “lived and breathed” as a Memphis teacher, principal, and iZone superintendent. She urged them to get inside of schools, stay student-focused in their oversight of the Partnership Network, and plan for a marathon instead of a sprint.

“The work can’t stop. The sense of urgency cannot stop,” she said.