At Magic Hands Barbershop in Memphis, boys fill the parking lot each summer day and often throughout the school year, too. They come to get haircuts or shop at the nearby convenience store. From time to time, they stand in front of the store, offering to do odd jobs so they can get something to eat at the Magic Wings next door. Sometimes parents leave their children in the parking lot, using them as bait to panhandle.

When boys congregate, too often, the impulse is to force them to leave, but shop owner Jason Bobo, and the men who run and visit the barbershop took a different approach. We decided to meet the kids where they are, literally; five years ago, in that parking lot, we started a boys mentoring program called Magic Dads.

Long before Shelby County School Board members issued their call to action to curb gun violence and youth violence on Monday, I have been working with my organization Magic Dads to do just that. As a special education teaching assistant, I know that everything children experience in their communities follows them through the schoolhouse doors.

Every day, children are walking to school and summer camp carrying the weight of bookbags and trauma. As a graphic artist, I saw their pain firsthand when I owned a custom T-shirt shop, and about 65-70% of my income was from RIP tees. These shirts, commonly worn at funerals and memorials, feature the name and image of the deceased, and about half the time, the faces staring back at me on shirts were young victims of gun violence, teens, and young adults who never saw their 30th birthdays. Some young boys had an entire collection of these shirts because they had lost so many friends, cousins, and classmates.

I saw how death’s repeated blows disturbed them. The academic struggles. The unhealthy relationships. The compulsive and unexplained misbehavior. The anxiety-driven fears. The depression. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 3.2% of children ages 3-17 have been diagnosed with depression, and 7.1% have been diagnosed with anxiety.

We need our elected officials from the local level to the national level to take immediate action to aid distressed families. Yet our General Assembly has yet to pass a measure that would increase funding for school counselors and lower the counselor-to-student ratio.

Now more than ever, we need additional counselors in our schools because homicides have spiked in Memphis, and virtual learning has created a distance in student-teacher interaction. In the fall, we’ll have the added challenge of returning to school during a pandemic that has led to increases in depression, trauma, and crime. Counselors and educators are the real frontline heroes and, simply put, we need more heroes in our schools.

Until then, the men of Magic Dads will continue our parking lot ministry. Personally, I am dedicated to this work because, in 2009, my cousin was shot and killed during a robbery, and I want to reach our Whitehaven youth before they’re staring at or holding a gun.

We want to expand our outreach to include tutoring and anti-gang, anti-drug, and anti-bullying initiatives, but all of us who do hands-on work in our communities need more support from local politicians, pastors, and parents. Because a lot of the distress stems from poverty, we need more job placement programs for adults and teens, and we need more financial literacy programs that are easily accessible.

We also need more foot soldiers to join us in the field as we do the gritty day-to-day work of coaching, counseling, and sometimes consoling children. With fewer press conferences and additional community collaborations, we can create more safe spaces for children in the classroom — and out of it, too.

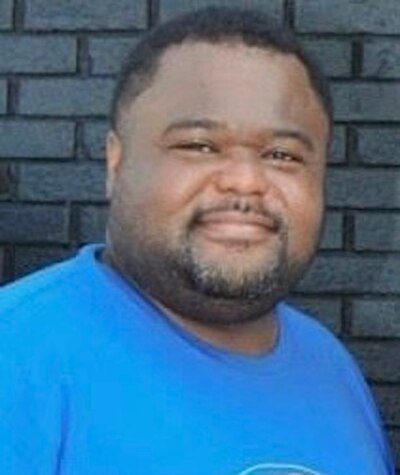

Dedrick Ford is an artist, special education teaching assistant, father of three, and the founder of Magic Dads youth mentoring program.