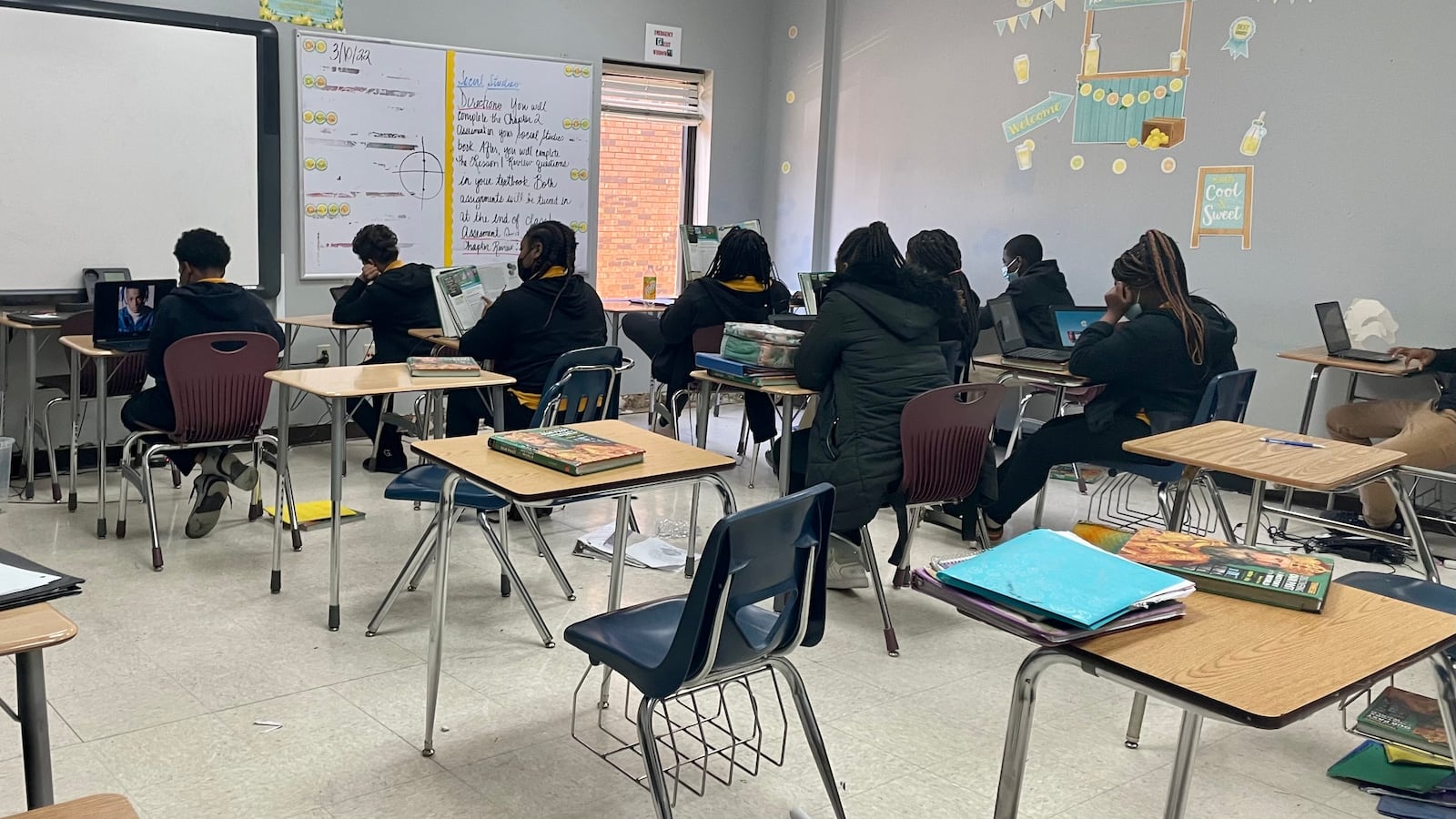

As sixth- and seventh-graders sat at their desks, hurriedly typing away on their tablets, it seemed like a typical Wednesday afternoon at Memphis Academy of Health Services’ middle school.

But behind the scenes, school leaders are fighting for the charter school’s life, seeking to overturn the Memphis-Shelby County school board’s January decision to shut them down.

“I just think that there is so much greater potential to help not only the students that we serve now, but our future students and the community as a whole,” said Alan Gumbel, executive director of MAHS, one of Memphis’ — and the state’s — first charter schools. “In no way can Memphis afford to lose institutions that are promoting a high-quality education and raising children to become good citizens.”

In a recent appeal letter sent to the newly formed Tennessee Public Charter School Commission, MAHS officials argued the state’s largest school district erred when it revoked the school’s charter based on the alleged criminal activity of three former school leaders.

They also contended that the district’s Office of Charter Schools thwarted MAHS’s attempts to communicate with them and failed to give proper notice or provide an opportunity to remedy issues that led to the charter being revoked. Memphis-Shelby County Schools officials declined to comment for this story and referred questions to the commission.

A December report from the state’s Comptroller of Treasury Office found that Corey Johnson, the former executive director of the schools, and fellow former administrators Robert Williams and Michael Jones allegedly used school money for trips to Las Vegas, a hot tub, seafood, NBA tickets, and auto repair, among other personal expenses, from 2015 to 2019. No trial for Johnson, Williams, or Jones has been set yet, a representative of the Shelby County Attorney’s office said, but they will be back in court at 9 a.m. April 12.

While MAHS officials recognize the gravity of the unlawful use of funds, in the statement they noted that many other organizations “fall victim to crimes” of this nature — especially when they’re committed by high-ranking employees who go to great lengths to conceal them.

In Gumbel’s view, revoking the school’s charter now will punish the 750 students in grades 6-12 who attend MAHS’s middle and high schools, and their dedicated teachers and school staff — some of whom have worked at the charter since it opened in 2003.

While MAHS predominantly serves students in the East Frayser and Raleigh neighborhoods surrounding the schools, Gumbel noted that many parents specifically chose the charter school for their children — for its tight-knit atmosphere, the smaller class sizes, quality instruction that focuses on health sciences, and the opportunities to dual enroll in college courses while still in high school.

Through collaborations with Baptist Health Sciences University and Southwest Tennessee Community College, students have the opportunity to leave high school with a leg up — real work experience or an associate degree — in the health science industry. MAHS focuses on nursing, biomedical sciences, sonography, health care administration, sports medicine, radiography, and population health, among others.

If a student can immediately get a job as a machinist in the health science industry after graduating high school and make $60,000 a year, “that’s an incredible opportunity,” Gumbel said, noting the majority of MAHS students are considered economically disadvantaged. Just over 30% of MAHS high school graduates in 2019 concentrated in a career and technical education program of study, according to state report card data, meaning they earned two or more college credits.

That experience, Gumbel said, is not something students can easily get elsewhere in Memphis. And he knows parents will be especially frustrated if MAHS closes and they must send their children to a lower-performing school.

A Memphis-Shelby County Schools report analyzing the impact of the MAHS closure found that a majority of both middle and high school students would be sent to schools with a lower school performance rating, a scale that weighs academics, growth, college and career readiness, and school climate.

While Memphis-Shelby County school board members expressed sympathy for students, families, educators, and other MAHS staff, they questioned why school officials failed to report suspicions of unlawful conduct for over four years and accused MAHS’s board of directors of failing to provide adequate oversight of school employees and finances.

“It is the desire of this board to ensure that every dollar allocated is used for the success of students. That’s why we sit here; that’s our responsibility, to make sure we do it right,” board member Althea Greene said at the Jan. 12 meeting. “We do care about students, we care about the staff there, but this board has a responsibility.”

In MAHS’s written statement to the Public Charter School Commission, however, officials contend that they only learned of the school’s former executive director’s “questionable transactions” when the Tennessee Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury launched its investigation in November 2019, and they didn’t realize “the full extent of these crimes” until the final investigative report was released in December.

Rather than waiting for the final report, MAHS officials emphasized that they “took swift action” to launch their own internal investigation, retained outside legal counsel to assist in the internal investigation and cooperate with the comptroller, and fired the employees involved, according to the written statement.

In the statement, MAHS officials also detailed their efforts to revise several procedures and policies, including revamping the organizational structure to increase oversight of finance and operations, requiring auditors report directly to the board of directors, and expanding its financial team, among others.

But the district did not consider any of these corrective actions, MAHS officials argued in the statement. Instead, the district “focused on the criminal activities of the former employees” and denied MAHS’s requests to provide the district with information.

It also denied school requests for information, including the documents the district was using as the basis for its recommendation to revoke MAHS’s charter, or closing impact reports, according to MAHS’s appeal letter.

MAHS also contends that the district falsely claimed that the MAHS board of directors concealed the comptroller’s investigation and refused to consider solutions other than closing the school.

“MAHS is committed to its students, families, staff, and neighborhood,” the statement reads. “If offered the opportunity, MAHS remains determined to correct any remaining issues and, if required, have a corrective action plan in place.”

That opportunity is all Veronica Fair-Miller wants for students like her two sons, who excelled at MAHS after transferring there from the Germantown Municipal School District for high school. She feels they will be unfairly punished if MAHS closes.

Fair-Miller’s older son, Cameron, graduated from MAHS in December, a semester early, and she said is thriving at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where he’s studying kinesiology and playing football. Her younger son, Christian, a junior at MAHS, has flourished in the smaller school environment and wants to finish his K-12 school career there, with his friends and the many educators who have supported him.

To Fair-Miller, Christian and his classmates deserve that — especially after the pandemic upended the last two school years, forcing them to learn virtually at home, away from their peers and teachers.

“I can’t describe the anxiety that we felt when we heard about the revocation of the charter. He has worked so incredibly hard and he really wants to graduate from the school he’s been attending for all of high school, the school his brother graduated from,” she said. “These kids have dealt with enough.”

The state Public Charter School Commission will decide MAHS’s fate at its next meeting on April 1.

Samantha West is a reporter for Chalkbeat Tennessee, where she covers K-12 education in Memphis. Connect with Samantha at swest@chalkbeat.org.