Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City schools Chancellor David Banks defended his record on antisemitism during a tense congressional hearing Wednesday, maintaining that schools have consistently responded to troubling incidents with both education and discipline.

Banks joined school leaders from Montgomery Country, Maryland and Berkeley, California, along with an American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney, in a hearing convened by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce about “confronting pervasive antisemitism in K-12 schools.”

Wednesday’s hearing came in the wake of previous high-profile committee hearings with university leaders that helped lead to the resignation of multiple college presidents. Republican members of Congress say the hearings have shown that higher education leaders have failed to adequately address antisemitism on their campuses in the wake of the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel by Hamas. They used the hearing to press K-12 leaders like Banks about similar concerns.

When he introduced the panel, GOP Rep. Aaron Bean said that the aftermath of last year’s attack revealed “some of the ugliest” ideas, and that “our education system has failed” to stop those ideas.

“Jewish students fear riding the bus, wearing their kippah to school, or even just eating and breathing as a Jewish student,” Bean said.

Banks, who presides over the nation’s largest school system with more than 900,000 students and roughly 150,000 staff members, acknowledged that the system’s diversity means “our classrooms have not been insulated from the global stage.”

“There have been unacceptable incidents of antisemitism in our schools,” he said.

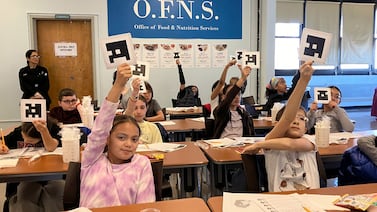

Banks emphasized both an education-focused response, including the introduction of several new curricula on preventing hate crimes and on the Holocaust and Jewish history. But he also said that Education Department officials have “removed, disciplined, or are in the process of disciplining” 12 staff members related to incidents of antisemitism.

At least 30 students have been suspended for their roles in antisemitic incidents, he said.

The incidents of hate in city schools following the Oct. 7 attack have not just been directed towards Jewish students, Banks noted. Out of a total of 281 incidents of religious bias in city schools since Oct. 7, 42% involved antisemitism, while 30% were directed against Muslim students, he said.

Asked by Rep. Jamaal Bowman, a New York Democrat and former Bronx public school principal, whether the city could combat antisemitism while simultaneously confronting other forms of bias, Banks said: “Not only can we, but we must.”

Banks rebuts claim about antisemitism among school’s students

Several of the most heated exchanges at Wednesday’s hearing focused on the fallout from a raucous student demonstration at Hillcrest High School in Queens — Banks’ alma mater — where students filled the hallway demanding the ouster of a teacher who posted a picture on social media shortly after the Oct. 7 attacks holding a sign that read “I Stand with Israel.”

After the demonstration, Banks called the “the notion … these kids are radicalized and antisemitic” the “height of irresponsibility.”

When Rep. Burgess Owens, a Utah Republican, challenged him about that comment, Banks told Owens he stood by it, and argued that “the entire school was not radicalized.” He added that “the kids who were responsible, who led that effort, engaged, clearly, in an act of antisemitism, and I dealt with that.” A “number” of these students were suspended, the chancellor said.

Banks also stressed that he removed Hillcrest’s principal, Scott Milczewski, midway through the year over concerns about his leadership. Milczewski was moved to a job in the Education Department’s central bureaucracy.

Several representatives grilled Banks on why Milczewski was still employed by the city’s Education Department and accused him of misrepresenting Milczewski’s status.

“How can Jewish students feel safe in New York City schools when you can’t even manage to terminate the principal of ‘Open Season on Jews High School’?” demanded Rep. Brandon Williams, a Republican from New York.

Banks responded that while he didn’t think Milczewski was fit to continue leading Hillcrest, employees have due process, and the chancellor doesn’t have the authority to terminate someone just because he disagrees with what they’ve done.

Banks also faced heat over Hillcrest from New York Republican Rep. Elise Stefanik, who noted that, earlier in the hearing, Banks appeared to answer “yes” to a question about whether staff members about Hillcrest had been fired, despite his continued role working for the department.

“That’s concerning to me that you have him in a senior position,” she said.

(Rep. Lisa McClain, a Michigan Republican, asked Banks, “So, you fired the people?” Banks replied, “Yes, we moved people, absolutely.”)

Emerson Sykes, the ACLU attorney, warned that while schools are required by federal law to respond to “hostile” educational environments, certain criticism of Israel and its government are protected under the First Amendment.

“Firing may be appropriate in certain circumstances,” he said. “But I think we need to think about how we can address antisemitism, change hearts and minds, make children safe, without only looking to the most punitive tool in our toolbox.”

Lawmakers highlight allegations of rampant antisemitism

Lawmakers raised concerns about the climate at other New York City schools in recent months.

For example, they brought up allegations of unchecked student antisemitism at Origins High School in southern Brooklyn that are now the subject of a federal lawsuit.

Among the claims in the lawsuit are that dozens of students marched through the hallways chanting “F*** the Jews.

Banks said Education Department officials found “no evidence” in their investigation of mass marching through the hallways with hateful chants. But he did say they found other “deeply troubling” antisemitic incidents at the school. He said he couldn’t comment further because of the ongoing litigation.

Rep. Virginia Foxx, a North Carolina Republican, asked Banks about a map of the Middle East in an elementary school classroom at P.S. 261 in Brooklyn that omitted Israel. The school’s Arabic arts program receives funding from a foundation tied to the Qatari government, and Foxx expressed concern that the foundation was pushing unvetted materials into city public school classrooms.

Banks, however, said that the map wasn’t provided by the Qatari foundation. The teacher found it on her own during a visit to Jerusalem, he said. And while Banks thought the map was antisemitic and had the map removed, after talking to the teacher, he said that she didn’t intend it to be antisemitic. (The map had been hanging in the classroom for more than a decade.)

Near the end of the hearing, Banks repeated a criticism that he had leveled in the days before his testimony: that the event was designed to produce “viral moments” rather than actual solutions to complex problems.

He also blamed the problem in part on young people’s emotional but misguided responses to what they see on social media.

“Ultimately, if we really care about solving for antisemitism, it’s not about gotcha moments,” he said. “It’s about teaching.”

Bowman and Connecticut Rep. Jahana Hayes, a Democrat and another former educator, emphasized the need to combat other forms of discrimination, including Islamophobia, alongside antisemitism.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.