Sign up for Chalkbeat Tennessee’s free daily newsletter to keep up with statewide education policy and Memphis-Shelby County Schools.

If it wasn’t for Ruby Bridges, Ben Williams’ circle of friends would be smaller — and whiter.

That’s why, when the 11-year-old Grahamwood Elementary School student read about how Bridges endured death threats and racial slurs to attend all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in 1960, he wrote a letter thanking her.

“You changed the world with your courage and your bravery,” Ben wrote. “Without you I might not have the same friends I have today… .”

Ben’s letter is now a work of children’s literature.

In 2022, Grahamwood’s third, fourth and fifth graders wrote letters to Bridges about how they wanted to change the world. After receiving more than 900 letters, a committee sent 10 of those letters to Bridges.

Ben, who was in third grade at the time, wrote about his dream for people to summon the courage to stop gun violence, just as Bridges, as a 6-year-old, summoned the courage to walk into an all-white school in spite of taunts and threats.

Bridges said Ben’s letter resonated with her because her oldest son, Craig Hall, was fatally shot in New Orleans in 2005. It was ultimately featured as one of 12 children’s letters in Bridges’ latest book, titled “Dear Ruby: Hear Our Hearts.”

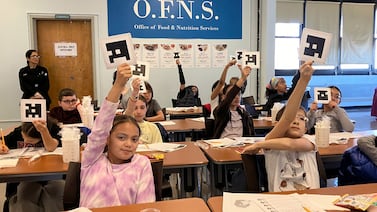

On May 4, Ben got a chance to read his letter in the book on stage alongside Bridges, who was in Memphis for the Ruby Bridges Reading Festival at the National Civil Rights Museum, where hundreds of books by her and other authors were given away.

“I hope I can help to change gun violence,” Ben’s letter reads. “Even though you can try and change kids’ points of view about gun control, you still need to change adults’ points of view. It’s like some of them do not understand the importance of gun control.

“If everyone had the courage you had, then maybe my dream would come true,” Ben wrote.

Ben said he was excited to meet Bridges, and to have his voice heard— which was why Bridges wrote the book.

For decades, she said, she had been receiving thousands of letters from children who learned of her story, and she thought it was past time to find a way to use them.

“I went through them, and I found letters from kids such as a little girl who said she had to be brave and call 911, ‘because my father was hitting my mom,’” Bridges said.

Bridges said she decided to solicit more recent letters from children on issues that they wanted to fix.

“I can’t begin to tell you how many boxes of letters we got,” she said. “I thought that as parents and as adults, we should hear their hearts, because many times, we underestimate our kids.

“Even at 6, my parents underestimated my thoughts,” she said. “So this was a way of showing the world what our kids were thinking about.”

Ben said one of the reasons he wants to end gun violence is that his mother, a child welfare lawyer, deals with many children who are exposed to gun violence.

It’s a huge problem. Last year, gun violence was the leading external cause of death for children in Tennessee. And in Memphis, by the end of 2023, trauma physicians at LeBonheur Children’s Hospital had treated 165 children for gunshot wounds — a record for a year — according to a report in The Commercial Appeal.

Nonetheless, Ben said he believes that people can fix that — just as Bridges helped to end legal segregation in New Orleans.

“Her story was about how so many people said ‘no,’ but she said ‘yes,’” Ben said. “All it takes is one.”

Bureau Chief Tonyaa Weathersbee oversees Chalkbeat Tennessee’s education coverage. Reach her at tweathersbee@chalkbeat.org.