Massachusetts charter school advocates had the wind at their backs as they set out to lift the state’s cap on charter schools in 2015. Polls showed strong support, deep-pocketed donors stood ready to fund their efforts, and a popular governor was set to champion their cause.

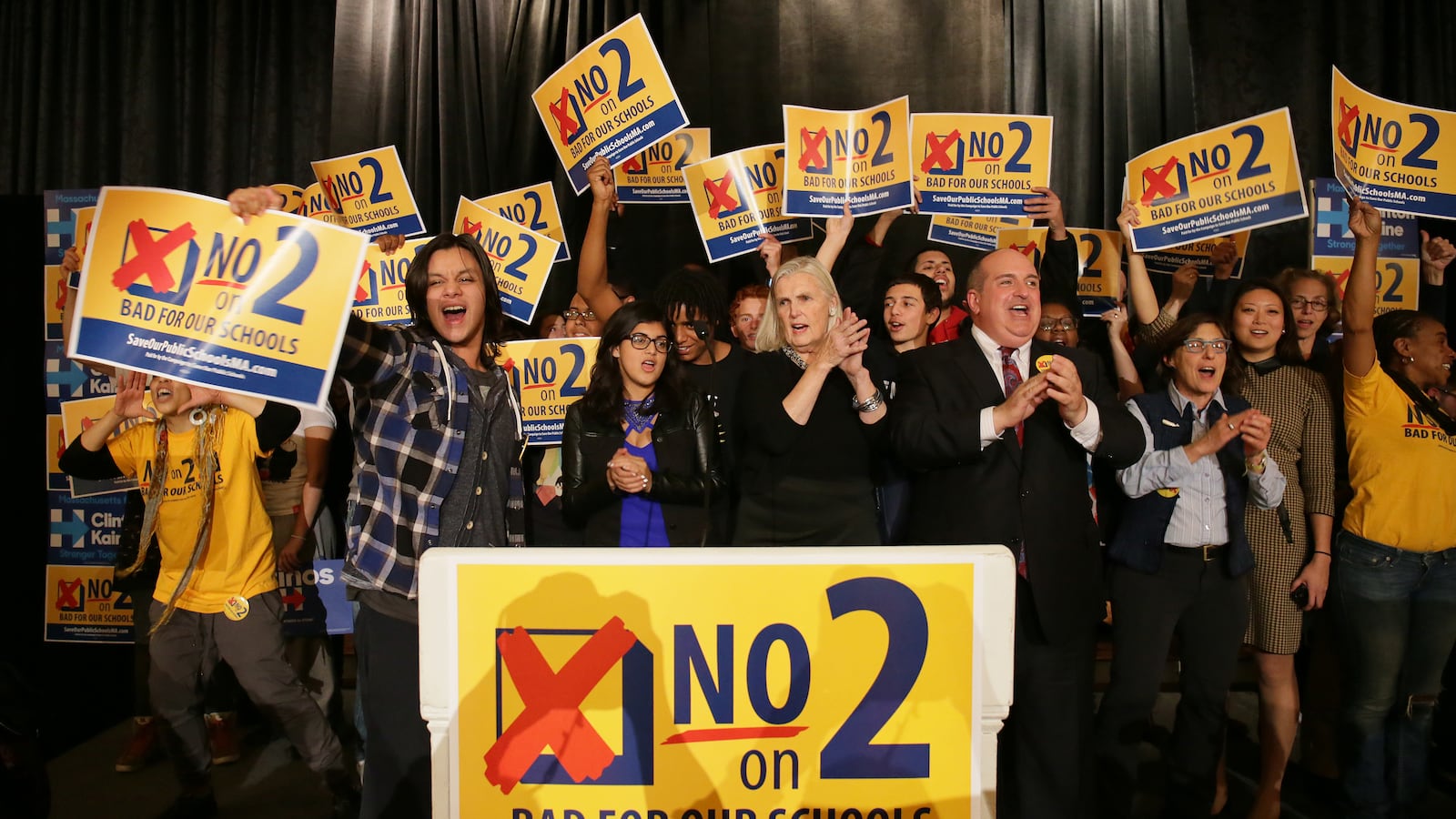

A year later, their effort would end in humiliating defeat. The ballot initiative known as Question 2 was shot down by 62 percent of voters, and opponents ended up with an anti-charter playbook that could be put to future use across the country.

National charter advocates saw it as a major setback, while opponents were emboldened.

“Question 2 marked an important flash point for education reform broadly and charters in particular,” according to a postmortem memo, part of which was obtained by Chalkbeat. “As a test case it was important. And it failed.” [Note: We later obtained additional pages and wrote about them here.]

That internal memo was commissioned by the Walton Education Coalition, a political advocacy group that spent heavily in favor of Question 2. (The legally separate Walton Family Foundation is a funder of Chalkbeat.) Its existence was first reported by Politico New York.

“A loss like we saw in Massachusetts is only made worse if advocates fail to engage in honest conversations about what happened and why,” Joe Williams, director of the Walton group, said in a statement.

The report is an unsparing account of charters advocates’ missteps: taking support that would later evaporate for granted, pushing inconsistent messages, and failing to unite the charter community or gin up much grassroots support.

Using in-depth interviews with key players, focus groups of voters, and pre- and post-election surveys, it makes clear that charter advocates underestimated their opponents, who had money to spend, a disciplined message, and compelling messengers: teachers.

What went wrong: The threat of a referendum backfired

The memo explains that charter advocates’ original plan was to use the threat of a ballot initiative to push state legislators to lift the cap themselves. If that failed, they figured they would win the referendum.

To try to force legislators’ hands, charter advocates were aggressive with the wording of the ballot question, which would have allowed a dozen new charters to open up anywhere in the state every year.

That strategy had worked before for education reformers in the state. Just a few years earlier, advocates for tougher teacher evaluations connected to student test scores had successfully used the threat of a ballot initiative.

But this time was different. Teachers unions were equally sure that they could prevail at the ballot. “The opposition was so confident that they told their allies not to compromise or provide any concessions to charter advocates,” says the memo, which was written by the Global Strategy Group, a consulting firm.

It also meant that charter school supporters were stuck with a ballot question drafted to force a legislative compromise, rather than one designed to win votes.

Charter advocates lost the messaging game

Opponents of the charter expansion stuck to a simple message: charter schools drain money from local budgets, growing at the expense of other schools and their students.

“The opposition focused on high quality public schools for all — and it worked,” the memo says.

According to polling reported in the memo, the message that resonated most with voters was, “We should improve public schools for everyone, not just those in charters.” Emphasizing that “Massachusetts charters have successfully helped students in underperforming areas” — a message beloved by policy wonks and newspaper editorial boards who point to research on Boston’s charter schools — resonated less.

“There was a very fundamental step that was skipped over and missed in this campaign … very simply the effort to introduce the issue to the public and to frame it,” one person interviewed for the report said. “It just didn’t happen.”

Democrats deserted charter schools

The campaign drew national spending and attention on both sides: Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders voiced opposition, and then-U.S. Secretary of Education John King spoke out in favor.

Some key Democrats closer to home, including some who had been supportive of charters in the past, like Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, came out strongly against the ballot initiative.

There was also a partisan divide among rank-and-file voters. By the end of the campaign, 57 percent of Republicans backed the measure, compared to just 27 percent of Democrats. That mirrors the growing partisan divide in charter support nationally.

“Considering the political climate of the 2016 election, the lack of endorsements and outright opposition from Democratic leaders exacerbated the partisan nature of Question 2,” the memo says.

Teachers were underestimated

The No side had something the Yes side lacked: a trusted messenger.

“Voters wanted to hear about the impact of charter schools from those who would be affected the most by a cap raise: teachers, parents, and students,” the memo says. “These voices were largely absent from the conversation on the Yes side. But voters turned to, and trusted, the opposition’s primary messengers: teachers.”

The Yes side believed it could rely on the state’s popular governor, Republican Charlie Baker, who filmed ads promoting the measure and whose top advisors helped run the campaign.

But voters were more willing to believe the teachers and school boards that opposed the referendum. “It kind of angered me. I was like, Charlie Baker, I’m not going to believe you over the teachers and city councilors that I know,” said one voter. “He’s a business guy.”

State and national teachers unions also helped close the gap with wealthy charter supporters, who still had a significant financial advantage.

“Although [charter] advocates still managed to outspend opponents by almost $10 million, the campaign anticipated that the ability to significantly outspend the unions and dominate the airwaves would be enough,” the memo said. The anti-charter advocates’ more resonant message, use of digital advertising, and strong ground game proved that incorrect.

Infighting among the charter community

While Question 2 opponents had massive grassroots support and a united message, the charter community was divided behind the scenes, the memo acknowledges.

Charters that didn’t want to expand saw no upside and serious risk in supporting the effort to lift the cap, and the Charter School Association “was hesitant to involve themselves.”

“The Yes on 2 coalition of advocates was, at best, fractured,” it says.

But the memo largely does not explain those divisions, and it barely mentions Families for Excellent Schools, the advocacy group that played a key role in the campaign soon after it entered the state. Families for Excellent Schools subsequently agreed to pay a fine for alleged campaign finance violations in the Question 2 election, and then shut down after an allegation of sexual harassment by its president, Jeremiah Kittredge.

“Initially, when FES came into town, their idea was to replicate the campaign that they carried out in New York City, which just wasn’t going to work here,” said Dominic Slowey, a spokesperson for the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association. “There was some friction for what the strategy should be, going back to when FES first came to town. That probably carried over into the campaign.”

Slowey said there was always tension between his group and Families for Excellent Schools, which he said was spoiling for a political battle, a strategy that was not cognizant of the existing cross-party support for charters.

More than a year later, their defeat continues to reverberate locally and nationally. Nina Rees, head of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, said in an email that one of the lessons she took from the defeat is how important it is to “Ensure voters (and importantly parents) understand what charter schools really are.”

In Massachusetts, Slowey says advocates are still in the recovery stage.

“We spent a lot of time from the mid ‘90s up until 2016 building a really positive image of charters across the state,” he said. “We’re going to go back to basic and rebuild the way we built it up to begin with.”

“It’s not going to be overnight,” he said. “We didn’t build it overnight — we kind of lost it overnight — so it won’t be rebuilt overnight.”

Read from the memo below. (This is the updated, more complete version.)