Right now, if you’re a teen mom in Colorado, there’s a good chance you have to clear a big hurdle to get state financial help to pay for childcare: That is, going to court to seek child support from your son or daughter’s father.

More than a dozen high school students—teen mothers from Denver’s Florence Crittenton High School—visited the Capitol building Tuesday to press for a law change that would eliminate that requirement for teen parents as well as domestic violence victims.

During a lunch break in a third-floor hallway, the students made their case to lawmakers passing by on the way to nearby meetings. Pausing in the middle of the hallway with briefcases or thick binders in hand, a couple legislators asked the girls to explain House Bill 1227.

In a quiet, halting voice, one student did just that.

The soft-spoken pitch to lawmakers wasn’t meant to benefit the girls lining the Capitol hallway. As Florence Crittenton students, they’re already exempt from the child support requirement because of an unusual one-time waiver granted to the school by the state a few years ago.

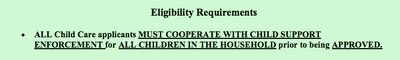

What the girls and their supporters wanted was to change the rules for their “sisters”—other teen parents who live in the 46 Colorado counties that have chosen to enforce the child support provision before handing out dollars from the Colorado Child Care Assistance Program, or CCCAP.

Proponents say the measure, which is scheduled for its first committee hearing March 18, would remove an intimidating obstacle that’s limiting access to childcare and forcing teen moms to drop out of school.

“You’re trying to get a 14-, 15-, 16-year-old to navigate a system that’s already difficult,” said Suzanne Banning, president and CEO of Florence Crittenton Services.

But some counties are pushing back against the bill in its current form, arguing that child support requirements can help families stay intact and set the stage for long-term financial support from non-custodial parents.

Pat Ratliffe, a lobbyist for the membership organization Colorado Counties Inc., said the counties she represents want to amend the bill to provide a shorter period of exemption from child support rules. The group hasn’t decided yet whether that narrower exemption should last a year, be tied to a grade-level milestone or something else.

“We’re trying to find our way through a foggy situation and do not only what’s best for the mom but do what’s best for the child and the family unit,” she said.

It’s not about the money

Opponents of HB 1227 say the purpose of enforcing the child support requirement for teen moms is not the money. Both sides agree that young fathers, especially if they’re still in school themselves, won’t have much to give.

“We don’t expect to collect money from these kids,” said Ratliff.

But she said going through the child support process is the “most obvious and most logical way to keep a father involved.”

She said when the mother names the father in court, it triggers various county services that promote the father’s involvement.

But supporters of the bill refute that, saying the policy’s not working. They say only about 2 percent of the 10,000 children of teen parents in Colorado have open child support cases, meaning the vast majority of young mothers aren’t seeking child support and whatever family reunification benefits come with it.

“The counties act as if they are so good at working with the dad and the mom…and that is just not true,” said Banning.

The teen’s experience

Between remarks by passing lawmakers on Tuesday, ninth-grader Gemini Leroy talked about the challenges she faced getting child care assistance even without a mandate to seek child support first.

“I just had a problem with CCCAP in general,” said the 15-year-old.

She said she’d re-submitted the paperwork twice, and finally obtained childcare assistance for her 14-month-old baby Starla after about seven months.

Leroy, who hopes to join the Army when she finishes high school, said with Starla’s father set to go to prison this spring, she’s not sure how she’d seek child support from him if it was required.

“It would be hard,” she said.

Even for teenage mothers who have a good relationship with their child’s father, the child support requirement can be feel like treading on thin ice.

Linda Becerra, a 10th-grader at Florence Crittenton, said she’d worry about how her daughter’s father would react, especially because he’s an undocumented immigrant.

“I think that he would take that as me being aggressive toward him,” she said. “The last thing I need is for us to have a bad relationship…I want to have good co-parenting.”

Right now, the father contributes financially to six-month-old Ebony, visits her on weekdays and cares for her on the weekend, said Becerra, who hopes to pursue a career in art or architecture.

A challenge to local control

Staff at Florence Crittenton, which enrolls students from multiple counties, began noticing several years ago that students were losing CCCAP money after failing to seek child support. School leaders subsequently negotiated a waiver from the rule with an official at the Colorado Department of Human Services.

That waiver, however, became a sore spot for some county leaders, who believed the state had interfered with local control.

“I think Florence Crittenton had a very good argument about why it makes sense,” said Erin Mewhinney, who last summer became director of the Division of Early Care and Learning in the state’s human services department.

Still, she said, “I don’t think it’s good policy to waive a policy for one provider…It should have been looked at as a larger policy issue.”

For that reason, Mewhinney said she declined New Legacy Charter School’s request for the same kind of waiver. The Aurora school, which opened last fall, serves pregnant and parenting teens.

There is another kind of waiver—a “good cause” waiver—that counties can grant on a case-by-case basis so women don’t have to go through the child support process. But supporters of HB 16-1227 say it’s inconsistently applied and out of reach for many domestic violence victims who don’t have the right records to prove the abuse.

Even if the proposed legislation passes, Mewhinney said a state task force will continue to look at the barriers that prevent teen mothers from accessing child care assistance. The problem may not be the child support requirement.

“We’re still not absolutely sure that’s why teen parents opt out,” she said.

Cultivating supporters

For a slow day at the Capitol—many lawmakers had already left to attend caucuses in their home districts later that day—the Florence Crittenton students found a receptive audience Tuesday.

When one of the bill’s prime sponsors, Sen. Larry Crowder, R-Alamosa, stopped by to introduce himself, he praised the measure.

“Personally, I think it’s overdue. I think it should have been done years ago.”

Rep. Jessie Danielson, D-Wheat Ridge, told the girls she planned to add her name to the sponsor list, which currently numbers 38.

When Sen. Mike Johnston, D-Denver, learned of the bill as he walked by, he said he’d be happy to support it. Then, the former principal gave a brief pep talk about the impact of a mother’s education on her child’s future.

“Your investment in your degree is the single best thing you can give them,” he said.