It was mid-morning, and Montbello High School teacher Holly Wells was shouting.

“You want to catch the frisbee as you’re running,” she yelled over the rumble and beeps of construction equipment. Her gym class has been meeting outside because the school’s gymnasium, like much of the campus, is inaccessible due to a multi-year renovation.

But Wells doesn’t mind. She’s dealt with noise and inconveniences before. To her, the temporary sacrifices are worth the long-term reward: A reunified Montbello High School in far northeast Denver, a community of largely Black and Latino residents that hasn’t had a comprehensive high school in more than a decade.

The reunified Montbello opened its doors last month, 42 years after the school welcomed its first students in 1980 and nearly 12 years after Denver Public Schools decided to close it because of low test scores and graduation rates. The district replaced Montbello with three smaller schools it hoped would do better and divided the building between them.

That division splintered the heart of the community. After years of advocacy by alumni and others, the district agreed to reopen and renovate Montbello, setting aside $130 million in bond money to do it. The school’s graduates are thrilled, its new administration is enthusiastic, and students said they’re excited to show what they can do.

“It’s essential we unite as a community to try to break down the stereotypes around Montbello and push our excellence because that’s what we are,” said senior Isaiah Torres, who previously attended one of the three small schools.

But there has been tension in the reopening, too. Not all of the teachers from the small schools were rehired. Some community members who advocated the hardest to reopen Montbello have spoken out against decisions by the new administration. And longstanding community groups said they haven’t felt welcome at the reunified school.

“Montbello High School is and always will be sacred,” said MiDian Holmes, a 1998 graduate. “When you attempt to re-establish and you want that same sacrament, you can’t cut corners. I’m not necessarily talking about cost. I’m talking about voices. … If you don’t create a process that’s inviting to those voices, you’re about to perpetuate more pain.”

High school united community when it opened

Carmen Livingston Fisher was a freshman when Montbello High School opened in 1980. She remembers the excitement: It was the first high school built in the Montbello neighborhood, which had been established 15 years earlier in 1965 when the city annexed more than 2,500 acres of land with the goal of creating affordable housing for families.

A half-hour drive from the city’s urban core, Montbello felt removed from the rest of Denver, alumni said, which made the community tight-knit. But when it came to school, Montbello’s children were scattered. Livingston Fisher remembers attending a temporary elementary school in an apartment building before being bused to a middle school across town.

The new high school was an opportunity to unite and show the strength of a neighborhood that often felt disregarded, Livingston Fisher said. As an eighth grader, she was among the students the school district asked to help choose the colors and mascot. Livingston Fisher doesn’t remember all of the choices. But she recalls picking the Warriors.

“We loved Montbello,” Livingston Fisher said. “Warriors just fit.”

From the start, Montbello was a powerhouse.

“Our basketball teams, football teams, everything from tennis to gymnastics to debate, we won everything,” Livingston Fisher said. “We all just had such pride in our community school.

“A lot of people tried to count us out because it was mainly minorities that went to the school so people didn’t think it was going to be as great as it was. But we were.”

The feeling continued into the 1990s, when Thomasyna Sweed attended Montbello.

“We had to fight this reputation that we were less than or we were ‘ghetto’ because the majority of the population was African American,” Sweed said. “In my family and other families, education wasn’t first, it was mandatory. You had to fight to break up the stereotype.”

In the 2000s, a new nationwide push to boost academic achievement put a bigger emphasis on standardized test scores. States and districts began judging schools based on their test scores, and Denver began chasing federal grants to “turn around” low-performing schools.

By 2010, Montbello was on the district’s list of schools to reform. While the graduation rate was above the district average, low test scores persisted despite a series of improvement efforts. The school cycled through principals and struggled with violence. Some community leaders called for dramatic changes, even as others pleaded with the district not to close Montbello.

At a contentious November meeting that stretched until 1 a.m., the school board voted 4-3 to phase out Montbello and replace it with three smaller schools: DCIS Montbello, Noel Community Arts School, and Collegiate Prep Academy. The vote was part of a package of reforms that made far northeast Denver into the district’s biggest turnaround experiment.

For alumni, the decision was devastating.

“When that was stripped away, you took away this space that … incubated our connection and that pride we held onto,” said Holmes. “It was the epitome of betrayal.”

Community calls for Montbello to reopen as one school

But that pride never went away — and neither did calls to reopen Montbello. The call grew louder in 2018 when the district held a series of community meetings in far northeast Denver. The purpose was to ask residents what they wanted in their schools. The answer was one Denver Public Schools wasn’t ready to deliver: Bring back a comprehensive high school.

Among the loudest proponents of reopening was a group of football coaches who worked for the Far Northeast Warriors, the regional team that was created after Montbello closed. The team draws players from several schools in the area, including the small schools that replaced Montbello, and the coaches were upset at the inequities they saw.

The small schools shared buildings but not bell schedules, making it hard for students to practice at the same time. The schools also had fewer course offerings, including college-level classes that help athletes boost their GPAs and get scholarships.

While graduation rates and test scores had improved since the closure, the progress was nowhere near what the district had promised. The community had paid a high price for little return, and now Montbello was one of the only neighborhoods in the city without what coach and parent Brandon Pryor called “a high-quality traditional option.”

“We deserve it,” Pryor told the school board. “Why don’t we? Why not?”

Instead of agreeing to reopen Montbello, the district came up with a compromise. In 2019, officials proposed rebuilding the aging campus to better serve the small schools that shared it, incorporating some of the benefits of a comprehensive high school.

But the community pushed back, and in 2020, the district relented.

“We’ve heard you,” then-Superintendent Susana Cordova said. She pledged to “work in collaboration with the community that has so clearly stated they want to reopen a comprehensive high school on the Montbello campus.”

In 2021, nearly 11 years after voting to close Montbello High School, the school board voted to reinstate it by closing the three schools that had replaced it.

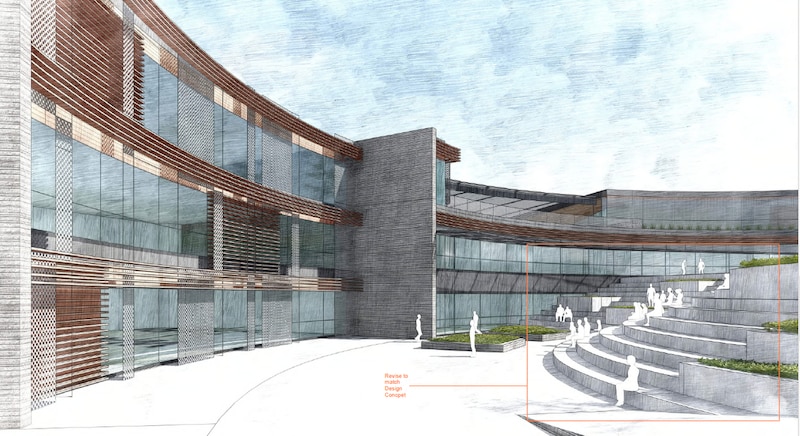

The board also greenlit a massive construction project to build a new state-of-the-art school while preserving parts of the original campus that alumni described as the heart of Montbello, including the auditorium, two gymnasiums, and the pool.

And the district hired Neisa Lynch, the principal of Collegiate Prep Academy, to lead it.

Community gets its wish: Montbello reopened Sept. 6

Montbello High School reopened its doors to 1,120 students on Sept. 6. On a recent weekday, Principal Lynch showed off the portion of the building that will be the school’s home for the next two years until the renovation is complete in 2024. The walls are freshly painted white and emblazoned with black-and-silver Warriors logos.

But the space feels transitional. Gone are Montbello’s infamous ramps, a signature feature of the school for the past 42 years. On the concrete floor where the ramps once stood are tables, chairs, and couches from the library, which was remodeled and reopened in 2018 after being shuttered for years. It’s now shuttered again, serving as the school’s makeshift cafeteria.

Outside, construction crews demolish the empty parts of the building. It’s a precision job; instead of wrecking balls, the crews use excavators like giant claw machines to munch away sections of the building, leaving gaps where the blue sky and clouds shine through. The new design will be full of windows and natural light, which was lacking in the old building.

Inside, Lynch said she’s working to build the type of school that community members said they wanted. In what she described as thousands of hours of meetings, Lynch said students, parents, and alumni asked for more academic courses and electives, ranging from career and technical classes like welding to college-level English and high school French.

Students wanted more leadership opportunities, Lynch said, so Montbello will offer student council, a Black Student Alliance and a Latinos in Action club, a mentoring program that pairs seniors with freshman, and a principal’s advisory committee that meets with her twice a month.

The comprehensive school will also offer more arts opportunities, including a band and orchestra, theater program, and dance and visual arts classes. Montbello already has a standout drumline, but Lynch is working to restart the marching band and add a mariachi band.

“We heard a lot from alumni about how there was excellence all over Montbello High School academically and athletically, and that’s what we really want to bring back here,” Lynch said.

Sophomore Josué Picazo said he’s most excited about the band program. He played the trumpet in middle school but the small high school he attended last year, DCIS Montbello, didn’t have a band. Picazo said he’s still getting used to attending a big high school, but he’s glad Montbello reopened because he’d heard so much about it from his older sister, who is an alum.

“I wanted to experience Montbello High School for myself,” Picazo said.

Some in the community are disappointed

Once the renovation is complete, Lynch also plans to bring back the varsity athletic programs that packed Montbello’s trophy cases in the ‘80s, ‘90s, and 2000s.

But athletics have been a sore spot in the reopening.

Lynch and her team did not rehire Tony Lindsay Sr., a community fixture and storied coach who led the regional Far Northeast Warriors football team to a state championship in 2021. The outspoken Pryor, who spent years advocating to reopen Montbello alongside Lindsay and his son Gabe, who is also a football coach, called it “a slap in the face.”

The Lindsays and Pryor now hope to start their own football program at a different school they lobbied Denver Public Schools to start, the Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy, which opened in 2021 and is modeled after historically Black colleges and universities.

Pryor doesn’t think Lynch should be principal at Montbello, and he disagrees with the decisions she’s made — a turn of events that has soured him on the reopening he fought so hard for.

“Before our school was even an idea, we were fighting for them to open Montbello,” Pryor said. “We were the catalyst.” But, he added, “If they were going to reopen Montbello like this, they should have left it alone and kept it how it was.”

He’s not the only one who’s disappointed. Julia Torres was the librarian on the Montbello campus last year, and she won widespread acclaim for her efforts to build a book collection that reflected her students. She said she learned her position was being cut when another staff member showed her the job ads for a pair of paraprofessionals to replace her.

“I’m not happy about the reopening,” said Torres, who now teaches English at a nearby high school. “I think there’s a lot of fake promises being made.”

Donna Garnett, executive director of the Montbello Organizing Committee, a local nonprofit that runs a food pantry, mental health clinic, and community newspaper among other initiatives, said her organization helped host visioning meetings for the new Montbello High School.

It seemed like the district was listening, Garnett said, but “once the new principal was hired, it felt like that ended.” After an initial meeting with Lynch to talk about the history of the school and hopes for the future, Garnett said, “we have not seen her since.”

“It’s not feeling like we had hoped,” she said.

Lynch disagreed that Montbello is unwelcoming. She said the school partners with eight different community organizations, including a group that supports female students and another that tutors freshmen. Montbello is hosting a meeting of the district’s Black Family Advisory Council in October, and the students are turning the school’s hallways into a haunted house for neighborhood children to trick-or-treat just before Halloween.

At a recent back-to-school night, Lynch said the Regional Transportation District was on hand accepting job applications from parents on the spot. She also hopes to host community college courses in English and Spanish for adults who want to learn another language.

“What I tell everybody is, ‘Absolutely come anytime and see the school,’” Lynch said.

But for the past month, she said, her focus has been on the students — and on making “sure that kids feel at home … and get used to their new school.”

Students form a bond

Students said that’s happening slowly but surely. On a recent morning, senior Jose Villa sat in the shade at a picnic table that was still wet with morning dew. For the past three years, he attended Noel Community Arts School and didn’t mix with the students who went to DCIS Montbello in the other part of the building. But that’s changing, he said.

As proof, he pointed to the teenager in jeans and a Colorado Rockies jersey who was riding the half pipes at the skate park next to the school. That kid went to DCIS Montbello last year, Villa said. We’re in school together now, he said, and that’s my skateboard he’s riding.

The new Montbello, Villa said, is “more company and more people I get to meet.”

That reunification — blending the three small schools into one, and blending old traditions with new — is at the heart of what Lynch said she’s trying to create at Montbello.

“What’s important, and that I don’t think people know, is we have over 100 years collectively of people serving Montbello that work in this building,” she said. “It’s me, as the principal, sure, but it’s the team that is building the school. And they truly are the heartbeat of this school.”

That includes Assistant Principal Kevin Wilson, who got a job at the old Montbello in 2010, just months before the district announced it was closing. He then worked at DCIS Montbello before transferring to Collegiate Prep Academy under Lynch. Now he’s back at Montbello, and he said he’s determined to help make the school the best in the city.

“Our babies out here deserve it,” Wilson said.

Torres, the senior, hopes to make the most of his time as a Warrior.

“I hope to leave a legacy,” he said, “for those here and those to come.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.