At the end of third grade, I wrote an essay in response to the prompt: “If you could wish for anything, what would it be?” My mom recalls that my response — “I want to feel safe in school” — nearly broke her heart. Since it was 1999, and I was a third grader at an elementary school just blocks away from Columbine High School, where gunmen had killed 12 students and a teacher just months prior, my response was not all that surprising. And yet, nearly 25 years later, my wish remains the same: I want to feel safe in school.

This wish remained front of mind when I was a third-grade teacher guiding my 8-year-old students through active shooter drills. The exact same wish often overcomes me as I try to ignore the relentless news stream of gun violence and drop off my two young children at school each day. Now, as a teacher educator in the School of Education at the University of Colorado whose work focuses primarily on preparing future teachers, I hear the same wish coming from my students. They, too, want to feel safe in school.

Incidences of gun violence are so commonplace that they can barely hold the 24-hour news cycle. In the past two weeks, there were three separate incidents within a square mile of our campus, and many of my friends and family didn’t even hear about them. And despite the prevalence of mass violence, including school shootings, we have to show up each day to teach, just as our students will be expected to when they have their own classrooms. We are all tired, but we have to go on.

As a teacher educator, I am expected to model the types of behavior with my students that I hope they will then enact in their future classrooms. I work to facilitate difficult conversations and hold space for their fears and anxieties while also pushing forward and instilling hope.

But what happens when I, myself, begin to feel hopeless? What happens when they look to me for answers I don’t have? Of course, there are many situations in my work where I don’t have the answers, and my students and I try to find them together. I intentionally position myself as a learner rather than an expert, just as I hope they will with their students someday. Though making peace with not knowing is much easier when it doesn’t feel like lives are on the line.

In recent years, the perception of teachers as martyrs has shifted from metaphor to reality.

As a profession, teaching is often framed as an act of martyrdom. Society will expect you to work long, difficult hours with few resources and little pay because the job is noble and thereby involves sacrifice. In recent years, the perception of teachers as martyrs has shifted from metaphor to reality. Future teachers are asking themselves, Would I be able to step in front of a gun for my students? And if the answer is no, Should I really become a teacher?

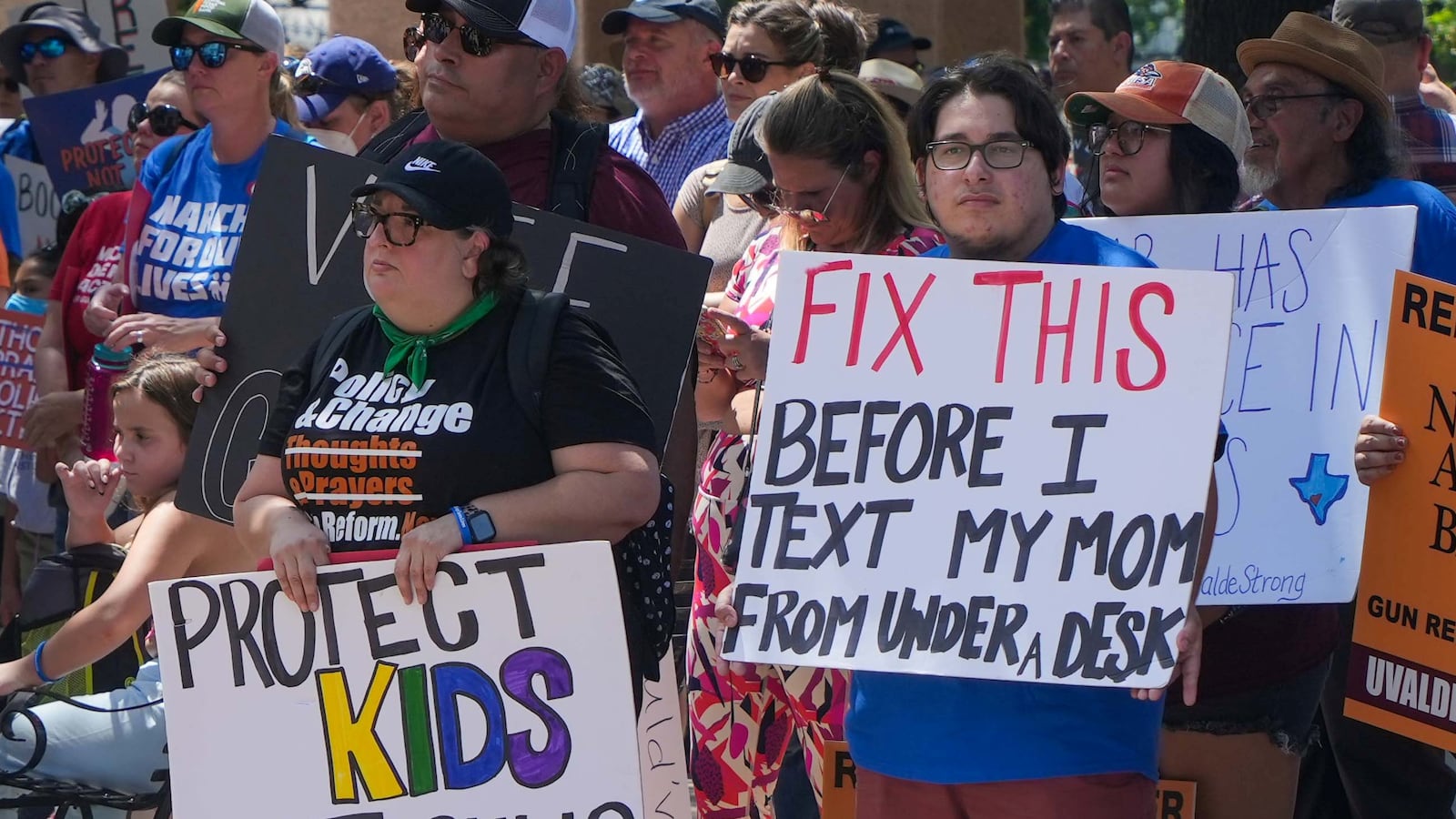

Much of my work centers on helping teachers find the power to imagine what is possible amid constraints instead of focusing on what they can’t do. Together, we work to find space to dream of what could be as a way to transform education from the inside out. Right now, though, everything we are doing feels colored by either real violence or the fear of it. My students want change; we all do. We want to know that if we are going to commit our lives to this work that those in power are committed to making it safe. Safety does not mean teachers coming to school armed. Safety means not having to think about guns at all while you work with your students.

I find myself wondering where these spaces for change might be. What if we refused to believe that our current reality is all that could be? Imagine if more educators unions took on gun lobbyists. Imagine if school boards called on state legislatures to make laws to protect children from gun violence. Imagine if elected officials banned the kinds of firearms being used to shoot children with the same ferocity and urgency that others are banning books and drag shows. Maybe reaching our breaking point finally gives us the opportunity to build something new.

Dr. Deena Gumina is an Assistant Teaching Professor in the School of Education at CU Boulder. Her work focuses on preparing teachers to work with and advocate for culturally and linguistically diverse students and their families. She lives in Colorado with her husband, her two children, and their chocolate lab.