Indianapolis teacher Jennifer Cook’s math lessons still feature goofy jokes written for a second-grade audience.

“Ten is such an important number. We have 10 fingers, 10 toes,” she told her students, wiggling her hands. Then with a little tilt of her head and half-smile, she added, “10 Oreos,” before pausing to get real with her students, “I wish, right.”

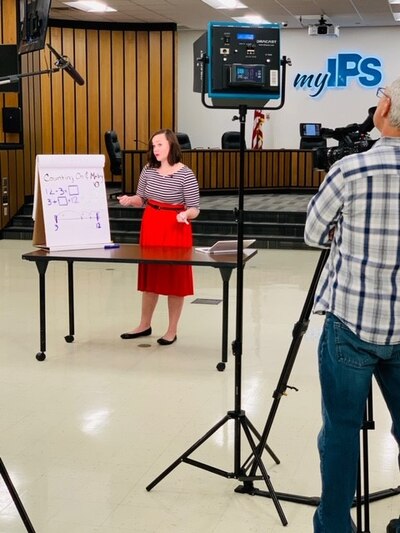

But instead of delivering her lines in person for the 24 second-graders in her class at School 82, Cook stood in front of a camera in the nearly empty board room at Indianapolis Public Schools’ central office. Her lessons in computation, number sense, and reading were broadcast on television to local students.

“I prepare more for this than what I would in the classroom, where it’s very natural and very comfortable,” Cook told Chalkbeat after she filmed her first set of lessons. But she still imagines her own students — not the many more children watching from home — as she teaches. “I picture their smiles, and I picture their little giggles. I know where they would laugh.”

The state’s largest district began airing lessons this week for two hours each weekday morning on MyINDY-TV, a sister station of WISH, in partnership with Circle City Broadcasting. The stations are owned by DuJuan McCoy, who attended IPS. The strategy is a way of reaching thousands of Indianapolis children who lack reliable or high-speed internet access at home — a glaring gap that has become more significant since classrooms across the city are closed due to the coronavirus pandemic and some coursework has moved online.

IPS estimates that more than 10,000 students lack reliable broadband. Citywide, school officials estimate about 39,000 students don’t have internet access at home.

The TV lessons focus on different elementary and middle school subjects each morning. Elementary and middle school students in IPS were given paper assignments, along with supplemental online work and videos. High schoolers were given laptops to take online classes.

So far, 26 teachers have filmed lessons after volunteering to participate. Filming occurs during their regular work hours, so they are not getting paid extra.

In some ways, the televised lessons look the same as they would if they were in the classroom. Teachers write on whiteboards and giant paper pads. They tell students to answer questions along with them or repeat words back to them, and they leave small pauses for responses.

“I try to talk to the camera like I’m talking to the students right in front of me,” said Stephanie Woods, a special education reading interventionist whose TV lessons focus on phonics and social and emotional learning. For video lessons, teachers have to be enthusiastic and clear because they cannot gauge students’ reactions and make modifications, Woods said. “You want to engage them, but you can’t see that engagement.”

Social and emotional learning lessons are challenging to modify for video, Woods said, because in a typical classroom, she would gather students in circles for discussions. But focusing on emotional needs is crucial during this crisis. “We’re struggling as adults with everything that’s going on,” she said, adding that she “can only imagine” how children and teenagers are coping.

Cook, the second-grade teacher from School 82, also volunteered to teach for television because she wants to soothe her students’ fears amid the coronavirus crisis. Since classrooms closed, Cook has not been able to get in touch with some of her students, and she wants to find a way to reach them.

“I’m hoping that they see me and they know everything’s gonna be OK,” she said. “I’m still here.”