Indianapolis Public Schools has never gotten middle school quite right.

In the early 2000s, the district combined grades 7-12 in an attempt to limit dropouts between middle and high school. But chronically low test scores prompted officials to get rid of that model beginning in 2017, pushing many middle schoolers into K-8 elementary schools instead.

Now, under a third consecutive superintendent, the district is weighing a new plan for middle grades: break up the K-8 structure and create standalone middle schools to better serve students amid declining enrollment.

The proposal from the district’s Rebuilding Stronger initiative — meant to shave costs as IPS loses students to charter schools — has divided the IPS community, even though IPS has not yet revealed the plan’s details.

The district will unveil the full plan Sep. 13, and officials are warning people not to leap to conclusions about what’s coming before then. District officials say the move would help offer higher quality education to all students, not just those in choice schools. Opponents of the proposal, however, argue the break up will hurt students academically right as students are recovering from losses during the COVID pandemic.

How many students would be affected and where they might move is unclear. It’s also uncertain when any changes will go into effect.

But not all K-8 schools will be affected. Innovation schools, most of which are run by charter operators that have special agreements with the district, will not be forced to break up elementary and middle grades unless they agree to do so.

Both the Path School and Matchbook Learning, two charters that took over underperforming schools, told Chalkbeat Indiana they will not break up their K-8 school structure, for instance.

The challenge is one of economies of scale. Traditional neighborhood K-8 schools are under enrolled but also spread thin, stuck with the fixed cost of running buildings that have fewer students than they used to. K-8 schools with fewer than 500 students, for instance, spend $1,500 more per pupil than schools with more than 500 students.

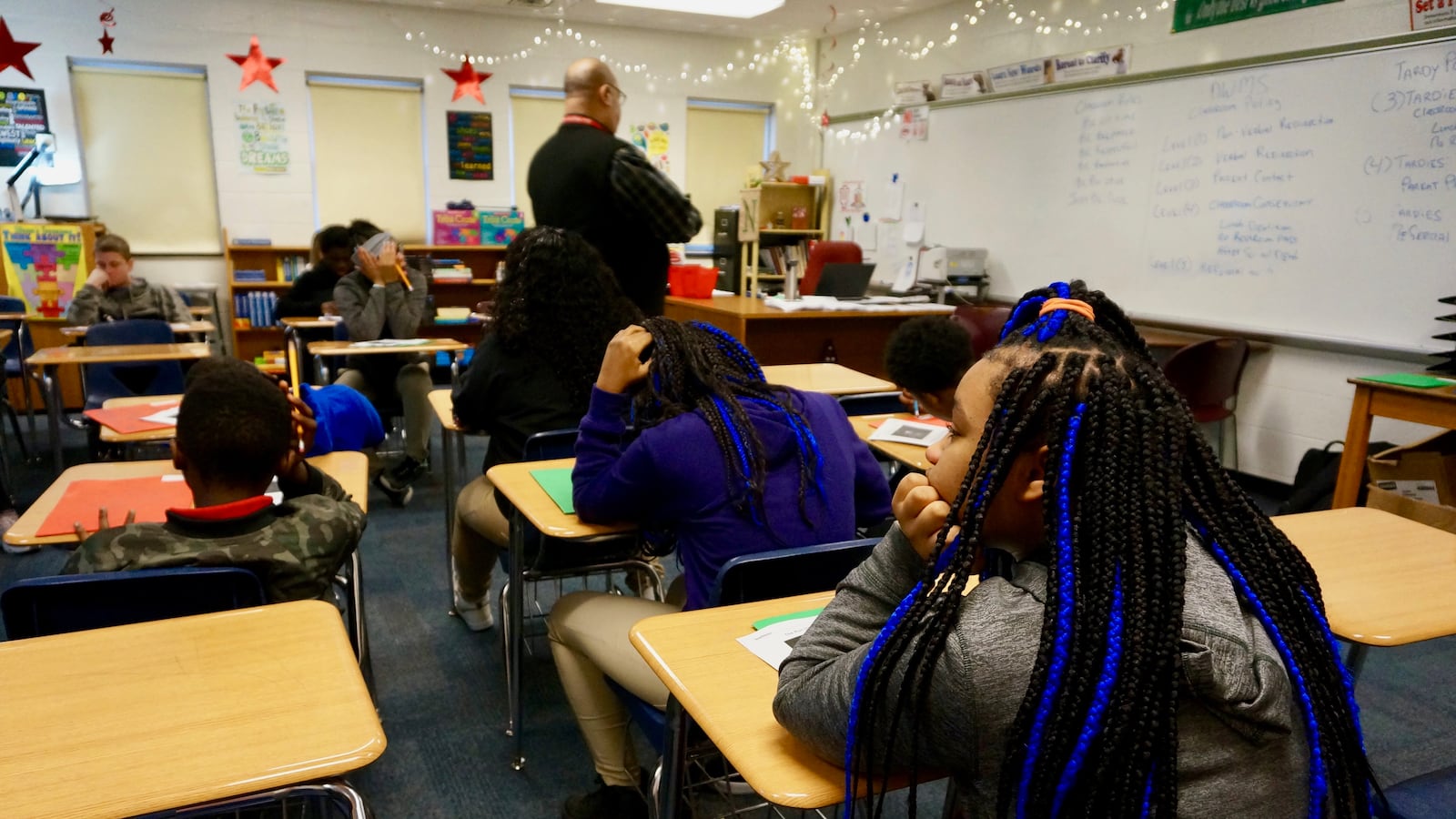

For James A. Garfield School 31 Principal Adrienne Kuchik, the fixed cost of her K-8 building means she is unable to offer certain classes.

“All middle school students deserve robust opportunities that meet their academic needs,” she said at an IPS board meeting last month. “As a K-8, I cannot offer algebra to the three students I have in eighth grade who are ready for that. I cannot offer a foreign language to my students, because I do not have the budget.”

But the idea that the district could split up K-8 schools into K-5 and 6-8 schools has angered parents at the district’s high-performing K-8 choice schools, such as Center for Inquiry schools, or those with special programs like Montessori. Parents fear their child’s grades will be eliminated or moved from existing choice schools.

Linus Schwantes-An, whose son is a third grader at the Sidener Academy for High-Ability Students for grades 2-8, said he’s unsure where Sidener will fit into the district’s K-8 shakeup. “We’re very concerned that they’re just going to close the school and we’ll be kind of back to square one,” he said.

Education research makes a strong case against standalone middle schools. One 2012 Harvard University study examining Florida schools, for example, found that students who transferred to a new middle school in sixth and seventh grades suffered a drop in academic achievement on state tests compared to students who stayed in K-8 schools.

That gap in test scores continued to widen over time, researchers found.

“When students transition from one school to another, for whatever reason there does seem to be an increase in potential for misbehaving and decline in academic achievement,” said Clara Muschkin, an associate research professor of public policy at Duke University who co-authored another 2006 study that found that sixth graders in a middle school had more behavioral infractions than those in an elementary school. “And that transitional effect seems to be particularly strong for children transitioning to middle school.”

But district officials argue grade reconfiguration alone is not the sole answer to the district’s middle school problems, but one part of an endeavor to bring academic and extracurricular rigor to all students.

“I think just saying we’re going to go back to a middle school model is not going to get us where we need to go,” said IPS board member Diane Arnold, who was on the board when the district last changed the middle school structure five years ago. “I think a complete redevelopment of the whole middle school experience is what will make this different.”

A history of struggle

In 2015, Indianapolis middle schoolers were struggling.

Three of every four failed the ISTEP, the statewide test at the time. And the district lost hundreds of students each year as they moved into middle school.

At the same time, middle schoolers were — and to some extent, still are — scattered throughout the district in a medley of grade configurations, including 6-12, 7-12, 7-8, and K-8.

The district’s response in 2017 was to separate roughly 2,030 students from six high school buildings.

Some students were moved into five elementary schools, which were expanded to include K-8. John Marshall became a 7-8 middle school, and later so did Northwest and Arlington. The district also created two new middle schools — Butler University Laboratory School 44 and Longfellow Medical/STEM Middle School.

Across the district, however, middle school proficiency levels in English and math on the state test have remained low — in 2022, just 12.6% of sixth graders and 12.8% of seventh graders were proficient in both subjects. Eighth grade proficiency was even lower at 9.9%.

But nowadays, officials are focused on other problems. Not only has enrollment in the district’s traditional public schools declined, but higher-performing choice schools with more programs and resources are also mostly white.

Today, middle schoolers have varying levels of access to diverse academic courses and extracurricular activities.

Eleven of the 12 middle schools offering Algebra I are choice schools, and only two of those serve a population of students of color above the district-wide median, according to a district presentation about the Rebuilding Stronger initiative in May.

Achievement is uneven, too.

At Rousseau McClellan Montessori School 91, a choice school, proficiency in math and English on the latest state ILEARN test ranged from 28.9% in 8th grade to 41.9% in 7th grade — well above the district’s middle school averages.

But at James Whitcomb Riley School 43, a neighborhood school just three miles away, middle schoolers are well below the district average: none of its seventh or eighth graders were proficient in both English and math in 2022. Just 2.3% of its sixth graders were proficient.

Those types of disparities and low scores are what district officials say they’re determined to address through the upcoming overhaul.

“What Rebuilding Stronger is trying to do is less about which grade configuration is absolutely right and is the silver bullet for solving all our problems, because that we do not believe grade configuration will do,” said IPS Chief Academics Officer Warren Morgan. “But what we’re trying to do is figure out what is the best configuration that will allow us to have an equitable and excellent experience across all types.”

Research bolstering arguments in support of the K-8 model and against standalone middle schools is dated, Morgan added.

And three of the five K-6 schools that added seventh and eighth grades in the last reconfiguration of middle schools had declining performance after the fact, noted Chief Portfolio Officer Jamie VanDeWalle. Those three schools — Washington Irving School 14, Wendell Phillips School 63, and Stephen Foster School 67 — became “restart” schools taken over by charter operators due to low achievement.

Grade configuration is the question getting a lot of heat from families right now, VanDeWalle said, but it’s hard to discuss it before the plan is formally released.

“Not that it’s all going to be crystal clear and everybody’s going to love it then,” she said. “But we do think maybe it will make a little bit more sense.”

Community pushback

Many parents of students in high-performing K-8 choice schools don’t want them broken up. They worry that their schools’ poor facility condition score would be used as an excuse to put them on the chopping block for potential closure or consolidation.

“We can all get behind making education more equitable and offering the choice or innovation schools to more students in more areas of town,” said Lindsay Conner, whose son is in third grade at Rousseau McClellan Montessori School 91. “But it seems like they’re wanting to replicate these successful K-8 school models by chopping them up and kicking them to the curb.”

Students, too, have voiced concern about being separated from beloved classmates.

“I really don’t want it to happen, because it’s not fair that you have to be with a certain grade level,” said Calvin Young, a sixth grader at School 91. “Like, let’s say there’s an 8th grader who’s friends with a kindergartner — not anymore.”

More broadly, taking away certain grades would also remove many older students who younger students may look up to, Calvin said.

Teachers have their own reasons to be wary of breaking up certain schools’ grade structure.

At William Penn School 49, the students Rosiland Jackson had her first year of teaching are now eighth graders. The K-8 setup allows teachers like her to remain connected with their previous students.

“It’s also great to talk to the middle school teachers to make sure that what we’re doing in third grade is going to put them on the right tract and trajectory to be successful in middle school,” said Jackson, an executive board member of the Indianapolis Education Association.

The real problem plaguing traditional K-8 schools, Jackson argued, is the growing number of charter schools. Some of those schools are part of IPS through its innovation network, while others operate separately.

“They have too many charters and innovations that’s sitting in our district that’s sucking the kids from there, and sucking the programs and the money out,” she said. “So you would be able to have an Algebra teacher, a middle-school algebra teacher, if the funding was in the building for that.”

Charter school proponents, however, argue that they are providing better quality options for parents, particularly for students of color who experience a large opportunity gap within traditional IPS schools.

District-affiliated charter schools have indeed grown as students have departed traditional district-run IPS schools.

In 2010-11, IPS had 33,408 students entirely within the district, according to district data. Now, the district has just 18,844 students in traditional district-run schools while the remaining 12,757 are in innovation schools, most of which are charters.

But some parents of children in neighborhood schools support the idea of separating the middle grades.

Natasha Hicks said she already plans to pull her two younger children out of James Whitcomb Riley School 43 and send them to a charter school once they get to fifth grade.

“I’ll put them somewhere else because starting at sixth grade, seventh and eighth, those are middle school ages, so they tend to have more drama,” Hicks said. “So if they’re looking to cut it off at fifth grade, I totally understand that.”

Brittany Maul, an IPS parent, is used to the standalone middle school structure in Pike Township, where her children previously attended schools.

“I think the age groups should stay together,” she said. “The smaller kids should stay together, and the older kids should stay together.”

What is the best solution?

Research suggests that all things being equal, a K-8 grade configuration is most conducive to students’ academic success as measured by progress on state tests, said Martin West, a professor of education at Harvard University who co-authored the 2012 study of Florida students.

But there isn’t one optimal grade configuration for every school system in the country, West cautioned.

“There are other considerations that districts can and should incorporate into their decisions about grade configuration,” West said. “Sometimes standalone middle schools create opportunities for more school-level diversity than do K-8 schools, which tend to serve a smaller catchment area.”

If IPS does break up its K-8 structure, then the district should focus on mitigating the harms of the transition from elementary to middle school, said Muschkin, the Duke professor.

“If children are having turbulent transitions because they’re feeling alone and isolated and not having guidance from significant adults, then that would be something to really work on,” she said.

In the end, the district’s plan may end up exacerbating the major problem it is striving to address: declining enrollment, driven by decisions made by parents like Hicks. At her high-poverty neighborhood middle school, proficiency in both English and math on the state ILEARN test falls well below the district-wide average.

Other parents with children in choice schools, fearful of the impending changes within the district, are already lining up options outside of IPS.

Schwantes-An said he and his wife chose to be a part of IPS when they sent their son to Sidener Academy. As a Korean-American immigrant, he values the school system because it was the first place he learned English and a place where he felt safe.

But with unknown changes ahead, Schwantes-An now reflects on the advice that coworkers gave him when he arrived in Indianapolis.

“Maybe, at the end of the day, I should have listened to my colleagues and sent him to private schools or something,” he said.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.